Glass display cases filled with scientific instruments line the foyer of the Physical Sciences F-wing. A seismograph, telescopes and a Hubble Deep Field image, among other things, rest inside the cases. Various knobs underneath each display can be twiddled around to start a pendulum waving or a glass vibrating. Some of the knobs work, but many of them don’t.

It’s an intriguing space, clearly meant to be interactive but in search of some much-needed attention. The most storied of these glass-enclosed spaces is also the biggest, the Robert S. Dietz Museum of Geology.

Tucked behind the striking Foucault Pendulum, the Dietz Museum was named after a former geology professor at ASU and a frontrunner in the field of plate tectonics and meteorite impact structures. The museum’s collection is the remnants of a much larger exhibit of fossils, minerals and meteorites. Like the displays outside, the room that bears Dietz’s name needs upkeep, but very soon it will cease to exist all together.

With the completion of the new Interdisciplinary Science and Technology Building (ISTB4) at the end of March, part of the School of Earth and Space Exploration (SESE) will be relocated and the space left behind reassigned, the museum included.

As the University expands its involvement in engineering and science, SESE director Kip Hodges explains that the faculty and students need laboratories with the technological capabilities required for their work.

“There’s a tremendous amount of effort by the university to improve research infrastructure,” Hodges says. “ISTB4 permits lots of exciting science to be done inside.”

Plans to build ISTB4 began in 2007, and it is fourth in a series of five research facilities on campus. Buildings one, two, three and five have already been constructed, says Richard Fisher, Director of Strategic Education and Public Outreach Initiatives for SESE.

Hodges says about half of the faculty in the department will move into the new building, but there is no specific group of people making the change. It isn’t all of the geologists or all of the astronomers moving. Instead, Hodges says a collection of faculty with “the most urgent research needs” will occupy the building, meaning research teams with federal grants who need high-tech equipment.

But the building is designed for more than just research: much of the first and second floors of the seven-story building will be dedicated to public outreach.

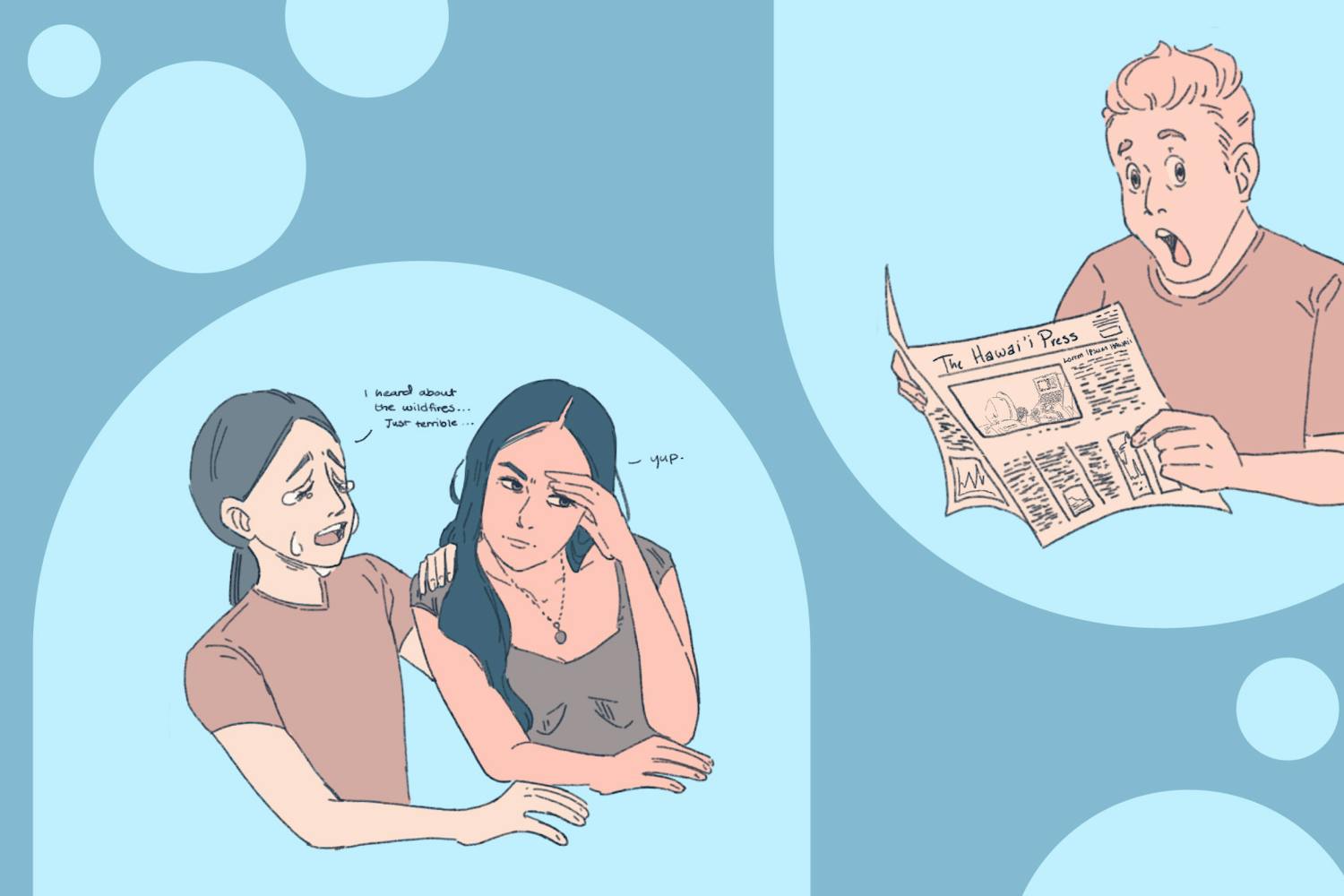

The Dietz Museum, the Mars Flight Center and the planetarium, all of which are open to tours to the public and school groups, are evidence of this mission. But in recent years the recession has limited such efforts.

After University funding cuts, Hodges made the decision in 2009 to let go of the curating staff at the Dietz Museum and to return the loaned collections.

Built in 1976, the museum was a pet project of Troy Péwé, head of the geology department at the time. Péwé collected many of the samples that make up the remaining permanent collection in the museum himself, says L. Paul Knauth, a geology professor at ASU.

“Dietz would turn over in his grave if he knew the museum was named after him,” Knauth says.

Although Dietz was an avid supporter of the museum, it was founded and maintained by Péwé, who fought to keep the space dedicated to outreach activities despite numerous efforts to shut it down, says Knauth. After Dietz’s death in 1995, the museum was named after him.

“ASU recognized this guy was great,” Knauth says. “But the honors institutions award are sometimes really bizarre.”

But times change, and the museum will finally be dissembled to contribute to the new exhibits in ISTB4.

With grant money and private donors supporting the construction of the new research facility, the School of Earth and Space Exploration can once again put public outreach in the spotlight.

“Through the new outreach program we can give something back to the community and students that they’re not paying for out of tuition,” Hodges says, highlighting that state funds have not gone toward funding the enterprise.

On floor two a new meteorite vault has been built for the Center for Meteorite Studies at ASU, which is the largest university-based collection in the world. There is also a larger display built so that more of the collection can be showcased.

The first floor of the building houses a 250-seat auditorium with high definition and 3D projection capabilities. The school hopes to use the theater for public viewing of planetarium-type shows, scientific movies and to enhance research presentations and lectures. Also on the first floor are glass-walled clean rooms and a mission control space where viewers can watch technicians and research teams at work.

“The whole idea is to help students K-12, college kids and the public to be able to appreciate how science is done,” Fisher says.

To accomplish that goal the center space of the first floor is dominated by the 4,300-square-foot Scientific Exploration Gallery. Inside the gallery will be interactive displays showing the history of earth and space exploration from the beginning to present-day research at ASU.

“The space is designed to cast the story of scientific exploration,” Hodges says.

It’s in the gallery that the Dietz collection will find its final resting place. The specimens will be scattered among the gallery, aiding in telling the story of scientific progress.

When SESE begins the process of moving in May, perhaps the geologist who gave so much to the scientific community, yet expected so little, will rest in peace.

Contact the reporter at klhwang@asu.edu