With the efforts of the renowned scholars of ASU Teotihuacan Research Laboratory, students have unique knowledge about one of the most fascinating ancient cities at hand, but Teotihuacan is still little-known to the public.

Teotihuacan: the major ancient city

Teotihuacan was one of the largest cities in the ancient world, located 30 miles from modern-day Mexico City. It occupied 8 square miles — a few miles more than all four ASU campuses combined — and was home to more than 80,000 people. It flourished from 100 AD to 650 AD, until it suddenly collapsed, leaving a pocketful of mysteries.

Despite all the uniqueness, Teotihuacan is not well-known in the U.S., professor emeritus George Cowgill said. It gets most of its attention from Mexico, Europe and Japan.

“One reason is because when a lot of people go there, they think it’s still the Aztecs, and the Aztecs were there 1,000 years later,” he said. “Another thing is that in English you can say Aztec and Maya very easily, but Teotihuacan is very hard for most English speakers. The very name is baffling, (which) I think it works against it.”

Five decades of hard work by Cowgill made his name almost synonymous with Teotihuacan. Internationally renowned, Cowgill has been an essential part of thrilling discoveries and brought the research laboratory with him to ASU in 1990. It's been the cradle of numerous research projects and an archive for artifacts and academic materials.

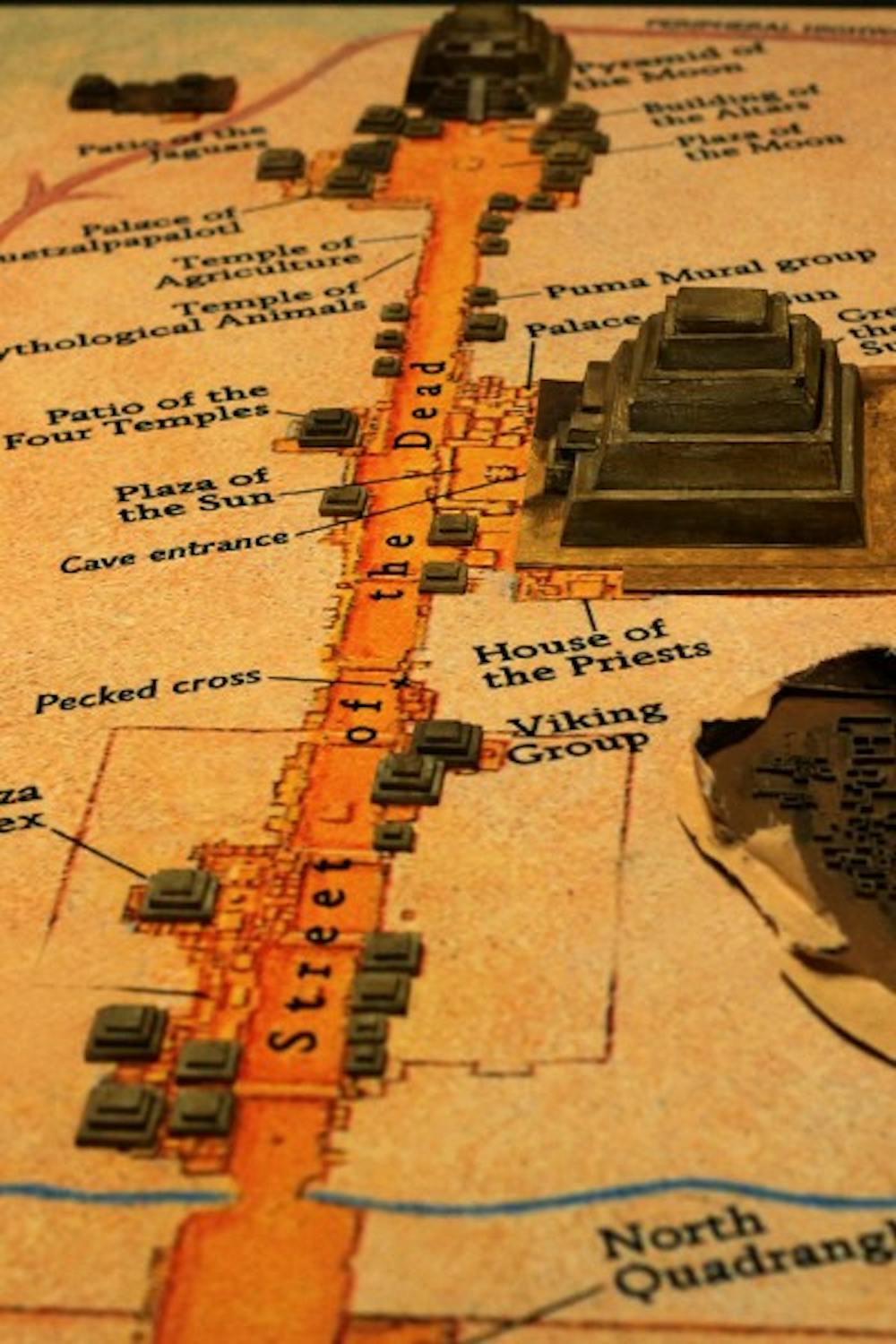

Among Cowgill’s contributions are assisting renowned Pre-Columbian researcher René Millon of the University of Rochester in creating a precise map of the entire city, composing a database of collected artifacts and excavating copious finds.

It is very important to understand what kind of city it was, Cowgill said.

Aside from being a UNESCO world heritage site, the most important finding is how large the city was, he said. In terms of specific findings, the biggest three pyramids are the most spectacular.

Sun Pyramid, Moon Pyramid and Feathered Serpent Pyramid frame the 1.5-mile-long Avenue of the Dead and are some of the biggest in Mesoamerica. They're thought to have been used for sacrificial rituals.

More than 130 people were excavated from under Feather Serpent Pyramid. Evidence suggests that those people were captive warriors, as they were found with arms tied behind their backs and their necks were bejeweled with pendants made of upper jaws, apparent war trophies.

Those people were buried in a nicely organized spacial distribution, not only with rich offerings, such as pendants, jade, obsidian and seashells from both coasts, but also with the strongest animals in nature—jaguars, pumas, wolves, eagles and even rattle snakes—that served as symbols of rulers’ power.

“Human and animal victims would be part of energizing pyramids,” Cowgill said.

Based on the patterns of the burials, archaeologists believe that more than 200 people were sacrificed and buried under Feathered Serpent Pyramid, some of which archaeologists intentionally left untouched for future generations.

The remains of the rulers were not found up to this day, which suggests that either they were cremated analogously to Aztec tradition, or more exciting finds are around the corner. Mexican archaeologists have almost cleared their way to the end of a recently found ancient tunnel 15 meters under Serpent Pyramid. Although nobody knows what’s buried there, researchers say there’s a chance for royal tombs.

Research professor Saburo Sugiyama has been working on mapping, architectural studies and city planning of Teotihuacan for 35 years. The city is extremely well-organized and amazingly precise down to one degree, Sugiyama said.

“I made an architectural mapping with machines, and the layout is so precise, it’s amazing,” he said. “The constructions go several kilometers, but they are exactly the same orientation.”

The reason for such accuracy is that ancient people used stars and planets for designing their cities. However, the orientation is not exactly directed to the north, it’s more than 15 degrees to the east. Twice a year on April 30 and Aug. 12, all the pyramids are oriented to the exact position at which the sun sets.

Why the city collapsed after six centuries of flourishing is still a disputed question. There’s evidence that the major monuments were set on fire, but whether it was brought by an internal uprising, invasion from outside or from Western Mexico is unknown.

“I think probably Teotihuacan was sufficiently weakened by internal political and economic problems, that it became vulnerable to an invasion by outsiders,” Cowgill said. “I think it’s a combination of growing internal problems and then probably an outside invasion.”

But the main question is not why the city collapsed, but how it managed to last for so long, Cowgill said.

“So far, no society has lasted much longer than that,” Cowgill said. “In many ways, the question in my mind is why Teotihuacan lasted as long as it did? Well, they must have been doing something right.”

Cowgill has almost finished his book about all different aspects of the city, and hopes that, along with the exhibition “City Life: Experiencing the World of Teotihuacan,” it will make the ancient city more widely understood by the general public.

Archaeology

Although Teotihuacan is one of the most-explored ancient cities, 95 percent is still underground. Archaeologists use special technology to look for objects, but most of the excavating is done by hand with the help of various tools, from shovels to needles.

“When we need small tiny things just you can see with your eyes, you excavate with a brush, (a) very small brush,” Sugiyama said. “I had to excavate sometimes with a needle. Something very small—tiny beads, or jade fragments or fishbones.”

Digging is just the beginning, and three-fourths of the archaeological work is the analysis of things that have been discovered, Cowgill said.

“Digging is the tip of the iceberg,” he said. “Even when you find something spectacular, you can say, 'Well, that’s exciting,' for a day, but then you have to say what it means. That might take many years to think about what it might actually mean.”

Another reason why conducting archaeological research might be a long process is that it’s very expensive and the funding is very little, Cowgill said.

“Getting a few hundred thousand dollars for an archaeological program is difficult, so that archaeology gets just a teeny tiny pittance really compared to other research fields,” he said.

However, the process of looking for an artifact is always a mystery and a suspense.

“Any place you dig, you get surprises,” Cowgill said.

Teotihuacan research took a new turn when the students and researchers got an opportunity to digitize the map of the city.

Sugiyama will start a new large-scale project in March. With the help of LIDAR — a remote sensing technology — he will be able to do very precise topographic 3-D mapping.

Researchers hope to integrate a previously made 3-D architectural map with this topographic map and achieve new results. For this costly project, he received a grant from the Japanese government.

“Based on the map we can do many, many things,” he said. “We can know more details about the city, precise expansion of ancient cities, people who lived in the areas and precise construction of the ceremonial zones.”

Teotihuacan at ASU

After more than eight years of preparations, the exhibition “City Life: Experiencing the World of Teotihuacan” opened its doors in October in the ASU School of Human Evolution and Social Change to offer students and the general public a unique, immersive experience.

Not only can visitors learn about the daily life of Teotihuacan, they are also encouraged to indulge their senses while experiencing the ancient city to the fullest.

Daily life of ordinary people is embodied in replicas and original murals, utilitarian ware, a very precise map, a model of the city and other daily objects. The full immersion is ensured by a soundtrack with authentic Teotihuacan sounds, tags reading “Please touch,” photos, videos and interactive video tours of the modern-day city, and even smells of chocolate and cardamon, which filled the air of the city 16 centuries ago.

Richard Toon, museum director and associate research professor, said the idea was to involve as many senses as possible.

“People more and more want to be immersed and involved, they want to participate and they like to be in environments," he said. "The whole idea of that is to get many different forms of engagement.”

The exhibit is unique in the sense that it doesn’t focus on the ritual buildings and objects, but draws people’s attention to the wide range of daily life items of the ordinary people. Implementing this idea was costly and difficult, Toon said.

“They are everyday objects, mainly, of ordinary people,” he said. “Museums don’t tend to collect those. They collect the spectacular ritual objects more likely. So it was quite difficult to find these materials, but we did it.”

The exhibits couldn’t be transported from the world heritage site and were borrowed from eight museums in the U.S. Once the items were obtained, museum studies students started generating ideas for how to realize the project.

“The desire was we used our own students build the exhibit,” Toon said. “And (they) pretty much mounted all of the materials, developed all of the film and all of the content.”

Following the theme of the exhibit, museum studies graduate student Brian Asdell, with the help of his students and interns, worked on recreating the utilitarian ware used in daily life by ordinary people, which does not often appear in museum exhibitions, he said.

In order to reach the maximum proximity to the authentic objects, the items were made in a traditional method—in an open fire pit—and required the simplest techniques. However, pinching and coiling produced “backward challenge,” Asdell said.

“When ceramic students start out they use these techniques,” he said. “But they generally only use them in the first semester and then everything after that is more elaborate. It’s actually very challenging to go back to the basics.”

Aside from the pottery, Asdell created murals and most of the visual decoration to bring the authentic atmosphere to the room. Many other students were also involved in creating authentic spirit with videos from the site and the soundtrack of original sounds.

This exhibit combined several academic purposes, such as featuring faculty research, celebrating Cowgill’s life work, and involving students, Toon said.

“I think it’s been a teaching opportunity, the opportunity to feature faculty research and give students real experience of doing a lot of this work,” he said. “It turned out to be great.”

For the public, the exhibit brings awareness of how general people lived many centuries ago in the major city of Mesoamerica at the time.

“We wanted to get students to understand that although it was a very ancient civilization, it still was a city with city life, and people were doing things and art and culture and ceremony and things like that,” Asdell said. “And people came from hundreds and hundreds of miles away to be a part of that city life.”

Entry is free and the museum will welcome visitors until May 16.

Awareness

To educate students on the subject, ASU launched a lecture series “Teotihuacan: Researching Ancient City Life in Central Mexico.” The first lecture, given by George Cowgill on Jan. 27, presented a broad perspective on the city.

For those who are interested in hands-on experience, the ASU Institute of Human Origins in collaboration with School of Human Evolution and the Social Change will offer a trip to Teotihuacan in October with the supervision of noted Mesoamerican archaeologist Ben Nelson and internationally known paleoanthropologist Don Johansson.

As a part of an immersive in-depth experience, people will be able to get behind the scenes one-on-one with the experts and peep at the mysteries the ancient city holds.

Reach the reporter at kmaryaso@asu.edu or follow her on Twitter @KseniaMaryasova