(Photo courtesy of HBO)

(Photo courtesy of HBO)The Emmy’s most interesting moment was on the red carpet, with an impromptu interview between TVLine and Kim Dickens. Dickens, famous for her role as Madame Joanie Stubbs on HBO’s "Deadwood," told reporters about a glimmer of hope for a fourth and final season for the epic western.

It should be noted that Dickens’s comments are very circumstantial and more reflective of the cast’s feelings toward the show than HBO’s, but it should inspire all of us for a better televisual tomorrow.

Today’s TV titans all have one thing in common: stylized violence as a means to profound ends. Whether the show is "Game of Thrones," "Breaking Bad" or "True Detective," this seems to ring true.

"Game of Thrones," a show of which I am a fan, has fallen under this violent spell. Although season four will go down as one of the best yet, its legacy as one of the most violent television seasons of all time will be riding shotgun.

This reliance on violence to send messages and move plots is growing stale as a narrative, but it is also creating an unsettling comfort with violence as means to an end.

Save for "Mad Men," I think all shows on TV are guilty of this — especially the average ones like "House of Cards," "Sons of Anarchy" and "The Walking Dead."

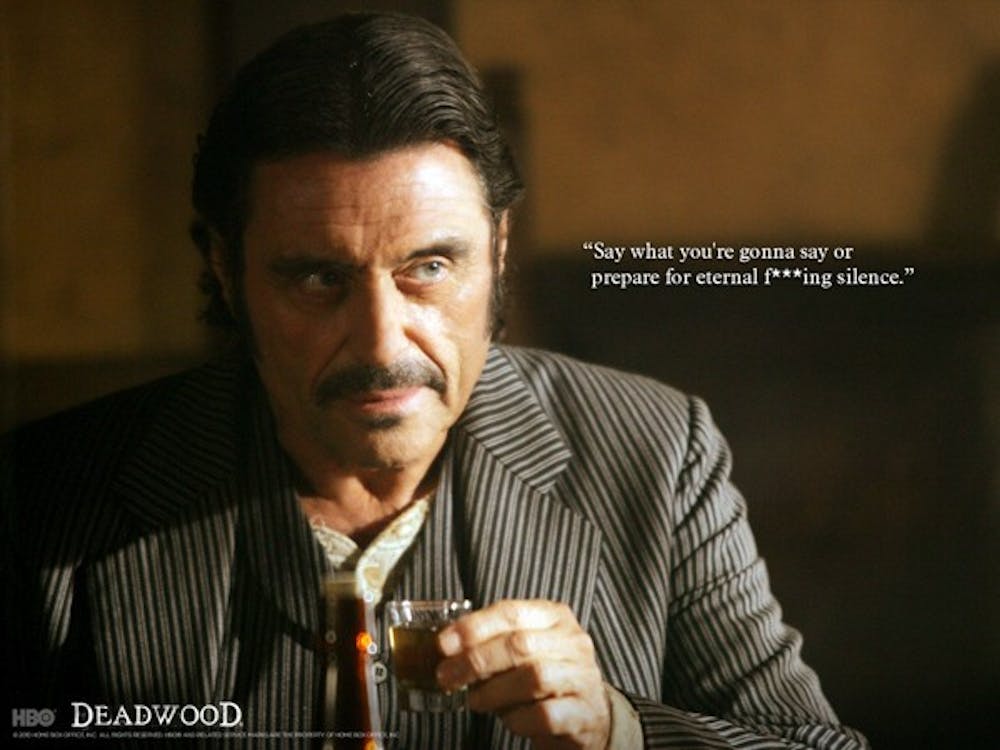

"Deadwood" is ostensibly another one of these violent TV shows. Its setting is established in a land that breeds violence, the South Dakota hills where various misfits, entrepreneurs and immigrants scour the hills for gold or the saloons for a drink.

Fortunately, the architect behind the show, David Milch, is a divine genius and saw the western town of Deadwood as something more than the typical western.

Milch sought to create an “organism” of a mining town that had genuine characters and moving cogs that would create an atmosphere beyond the screen. In a sense, the character plots of "Deadwood" live on despite the camera lens. The emphasis of the plot is much more on the build up and fall out of events versus the event itself.

For example, in the beginning of season three Sheriff Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant) is summoned by goldmine tycoon George Hearst (Gerald McRaney). Midway through their conversation, one filled with political and personal innuendo, Bullock gets the idea that local innkeeper and gossiper E.B. Farnum (William Sanderson) betrayed a secret that could give Hearst political advantage. As a result, Bullock storms downstairs and, to put it lightly, beats the snot out of Farnum.

The scene is disarming. It’s a departure from the usual by-the-books attitude of the Sheriff. The scene is short. Little emphasis is put on the actual beating, but all of the implications leading up to it and the chain of events that will come from it.

This scene is how Deadwood does things. Milch knows that audiences’ hearts race at violence, but he captures that infatuation and uses it as a vehicle for complex, genuine and unparalleled storytelling.

Thus, in the midst of the streaming age where a show like Deadwood can be digested en masse, it would be a benefit for all if the show saw its conclusion.

Reach the reporter at zjenning@asu.edu or follow him on Twitter @humanzane