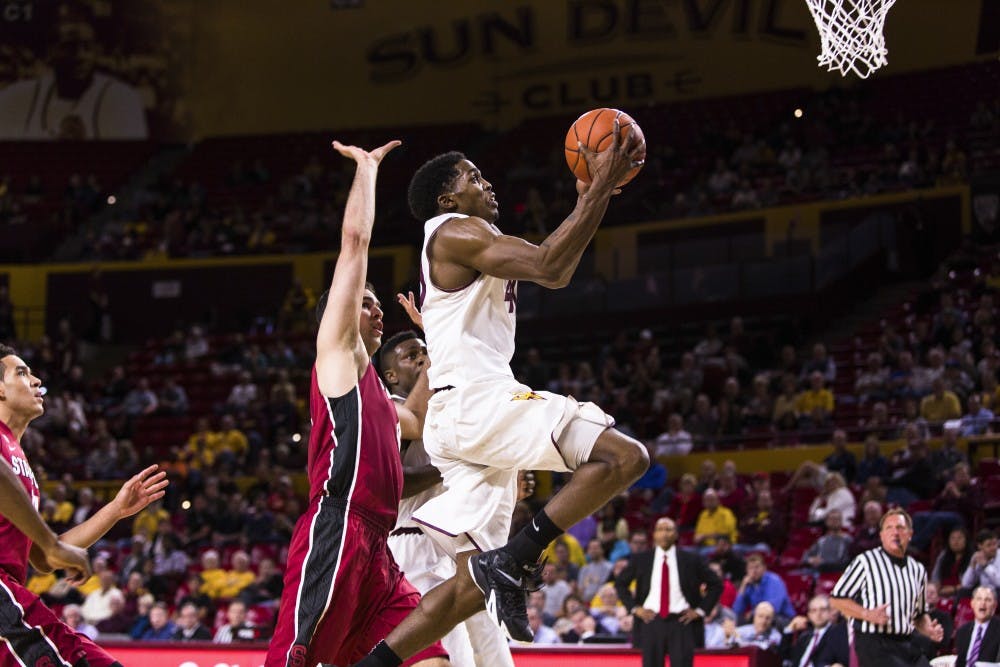

Mackenzie McCreary does the #icebucketchallenge.

Mackenzie McCreary does the #icebucketchallenge.All it takes is an idea, 140 characters and a hashtag.

A like, a retweet, a share — with a single click of a button, a message spreads through the various channels of the web to the far reaches of Wi-Fi connectivity. An addicting catchphrase finds a home across Facebook timelines, Twitter feeds, Instagram reels and Youtube videos, helping to perpetuate awareness and inspire action. Suddenly, the important idea in that tiny hashtag becomes a massive phenomenon. Everyone’s talking about it. It went from a tiny community of activists, across the nation and flew over oceans and borders.

A new update brandishing the specialized hashtag appears every couple of minutes.

Pretty soon, it’s gone viral.

It headlines national media outlets and celebrities start lending their voices to the cause. Its range spans between longtime supporters to new converts, to parodies, to angry annoyance.

And that’s when you know the campaign has really made it.

Whether the movements are worldwide, or just campus-wide, they all have the ability to create change.

Political science junior Jordan Uter used to do it all the time.

He’d be out with friends and see a girl across the street. Whistling and yelling ensued.

Despite essentially being raised by his mother and two older sisters, he didn’t see a problem with catcalling and hitting on women as they walked down the street.

“My friends and I used to do that when we were younger because that was just the culture that we grew up in,” Uter says. “I never really realized that you can’t just yell at a girl across the street just because she’s wearing booty shorts. That doesn’t give you permission to do that.”

While Uter continued studying at ASU, he wanted to change up his routine classes.

“Political science is the study of power, so you’re always learning about power, which is really like a man thing,” Uter says. “I wanted to switch it up and see things from a woman’s point of view.”

Uter signed up for WST 375: Women and Social Change. Not only did he want to learn about power in relation to women, he also wanted to understand his mother and sisters’ points of view.

“It’s hard being a woman,” Uter says of what he’s learned. “Women are continually objectified by men and I never really thought about that. But I’ve also learned that women have done a lot of things to create change throughout the world.”

As a critical component of WST 375, students organize the ASU Clothesline Project, headed by Alesha Durfee, associate professor in the School of Social Transformation.

The Clothesline Project offers victims of domestic violence a creative way to talk about their experience and spread awareness about the reality of domestic abuse.

Victims come together and create T-shirts that illustrate their experiences. The shirts are then hung on clotheslines on Hayden Lawn for all to see.

“So then, when people walk by Hayden Lawn, they’re going to be able to see it and realize that this is an important issue, this isn’t something you just see on TV, this really happens to people,” Uter says.

The class works with victims ranging from adults to children, as well as high school students who are also helping to organize the campaign. Uter says this is important because it essentially brings awareness to the root of the problem.

“You have to teach young men when they’re very young that you cannot harm a woman,” Uter says. “You even have to teach women because men are in abusive relationships as well, so we’ve got to teach them that you cannot harm men.”

The class is split into groups with each group working the campaign in a different way. Uter’s group decided to utilize Facebook to spread the word about the Clothesline Project and its upcoming events. According to Durfee, this is the first year students have made a concerted effort to utilize social media for the project.

Uter says he is optimistic about the use of Facebook in the campaign in reaching a wider audience and people who may be familiar with the situation.

Within two days of launching their Facebook page, the ASU Clothesline project had 175 likes. At the time of this article, a week later, the page has 255 likes.

This is not surprising, as millennials are constantly discovering new causes to support through social media.

It’s something we do everyday in coffee lines and at bus stops. We even do it during awkward silences and lulls in conversation. Sometimes, we don’t even wait for the silence — we multitask. Social media is a rapid-fire tool of convenience in spreading information.

According to a study conducted by the American Press Institute’s Media Insight Project, “Seven in ten adults under age 30 say they learned news through social media in the last week.”

The study also reported that 13 percent of adults under age 30 claim social media as their preferred way to receive news.

The ease in practice and the reach of information places social media in the top tier of tools used in spreading information and ideas, which makes it a necessary tool for social activists with a message.

“I can’t imagine someone not using social media to organize,” says Alex Halavais, associate professor in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences. “You would be really stupid to do otherwise.”

Halavais specializes his research in society’s use of social media and its connection to social activism campaigns. He says that the main contribution social media provides for activists is what it does for society as a whole: It allows us to organize.

“At a basic level, there’s coordinating groups that already know what they’re doing and letting them get together,” Halavais says. The second basic tool is the convenience it provides in creating groups and bringing more people into the movement who haven’t met before.

#FlashbackFriday

Widespread social activism always had its challenges, but people always came together regardless.

“Before social media it was all just word-of-mouth, you tell a couple friends, they tell a couple of their friends, maybe you’ll get three of those people to come,” Uter says. “Now there’s such a wider audience that you can reach through social media, just because someone could be friends with 2,000 people.”

Even in the early days of the Internet, people used the medium to organize and bring people together.

Retha Hill, professor of practice in the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, says online social activism has been very effective over the years.

“Way back, in the mid-90s people could submit petitions for various things and people did,” Hill says. “Even when the Million Man March became such a phenomenon, it was mostly email.”

Louis Farrakhan, a minister with and leader of Nation of Islam, organized the Million Man March. He invited African American men to convene in Washington D.C. “to declare their right to justice to atone for their failure as men and to accept responsibility as the family head,” according to the Nation of Islam website.

More than one million men came together on Oct. 16 to demonstrate on Capitol Hill. One of the main organizers of the march, Conrad Worrill, said, “The Million Man March was one of the most historic organizing and mobilizing events in the history of black people in the United States,” according to the website.

“So if you look at the beginnings of that, it’s always been a part of the web as we know it,” Hill says. “What’s happening in Ferguson, in Hong Kong, around Kony: This is an outgrowth of those early days of activism.”

With the development of social media giants like Facebook and Twitter, social activist groups have found a useful tool for getting their message out there, for better or for worse.

#Kony2012

The overnight phenomenon began with an informational Youtube video and a call to spread the word.

In March of 2012, the Invisible Children campaign released a video intended to make Joseph Kony, the leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Africa, famous.

According to the Invisible Children website, the campaign was based on two questions: “Could an online video make an obscure war criminal famous? And if he was famous, would the world work together to stop him?”

The 30-minute video was uploaded to Youtube and implored viewers to spread awareness about Kony and his army of child soldiers in the longest armed conflict in Africa’s history.

But the system was flawed.

Critics attacked the information presented in the video, the way the group utilized donations and their entire social media campaign.

Management freshman Katie Oakes says she felt that Stop Kony sounded like a conspiracy theory in the beginning. She says it was effective in spreading awareness, but not as effective in creating tangible change.

“I didn’t know what we were exactly trying to do,” she says. “[The] Kony [campaign] was just watching a Youtube video and mentally understanding what’s going on.”

“I think it did a good job with bringing some money and some attention, but in terms of actual practice it was a great campaign to ends that were a little bit difficult,” Halavais says. “I don’t think it stands out as a particularly good exemplar of how to do this, except the fact that they were very good at manipulating the social media.”

According to the Invisible Children website, the film reached 100 million views in six days with 3.7 million people pledging support for the group’s efforts.

During this time, everyone knew about Kony. The hashtags #StopKony, #Kony2012 and #makeKonyfamous spread through the Twitter-sphere. People printed posters, bought bracelets, signed petitions and donated money. The “Cover the Night” protest aimed to spread the fame by covering cities in “Stop Kony” posters.

“The situation that the Kony campaign was addressing had been going on for a number of years, so it was nothing new,” Hill says. “But all of the sudden this Kony thing came out of the blue and really caught the attention of a lot of young people because there was a concerted effort to try and hunt him down.”

So, was it effective?

“I think Kony 2012 was more passive because nobody really did anything, he’s still out there. Everyone knows about Kony, but no one follows up on it,” Uter says.

“It’s kind of the poster child of ‘slacktivism’,” Halavais says. “I don’t want to be totally dismissive but if you could use those same methods to develop a concentration of interest around something that you could have a more effective impact on, I think it would be better.”

#Slacktivism

“Slacktivism,” or “lazy activism,” includes changing your profile picture, liking and sharing posts. Halavais says many people dismiss this as activism.

In a now-closed conversation onwww.ted.com, users discussed the idea of ‘slacktivism.’

“The so-called slacker activism theorizes that people on social media platforms only participate in feel-good clicking (they may like something, but have little care for it later), which doesn’t cause real change and action in the world," user Michael Clausen said in the conversation.

Many, who decry “armchair activism” because of its failure in producing tangible change, share this sentiment.

Kyounghee Kwon, assistant professor in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, says she tends to follow scholars arguing that this type of activism can muddy the basic effectiveness of a campaign.

“They [scholars] argue that light-weighted forms of participation help blur the boundary between free-riding and participation,” she says. “Having such a blurry domain may facilitate the process of collective actions.”

However, many scholars including Kwon and Halavais argue that this type of activism does have value.

“I hate the term ‘slacktivism,’” Halavais says. “I think that, A: It’s valuable by itself because it gives you the idea that there’s a movement, and B: That it can provide a ladder for some of those people to step up in a way that they might not have been able to before.”

Kwon says that although this type of participation is “a lazy form of participation,’ it does have its positive side effects.

“Wouldn’t it still be better to have one additional lazy participant rather than not having it?” she writes in an email-based interview. “Now that social media offers a role of ‘button-clicker,’ they will at least click the button and share the information.”

Halavais says that an effective social media campaign needs to include these basic, low-level forms of participation because it is through them that a campaign garners the most attention.

But this can’t be the only tool activist groups use. Halavais says there needs to be something more.

One of the more recent viral activism campaigns has arguably taken that additional step to be effective through social media.

#ALSIceBucketChallenge

Everyone was doing it.

Last summer, Facebook exploded with videos of people flinching and squealing as buckets of ice-cold water are poured over their heads.

Once the deed is done, the body shivers into numbness through vain attempts at drying off and getting warm again. The challenge was intended to show people what it is like to have Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, ALS is a neurodegenerative disease that slowly kills off the motor neurons in nerve cells found in muscles throughout the body. The brain can no longer control muscle movement and patients often become paralyzed as the disease worsens, according to the ALS Association’s website.

The challenge began through a series of men with ALS, who posted videos on Facebook of themselves completing the ice bucket challenge with the hashtag #StrikeOutALS. They then challenged friends to do the same, and soon it went viral.

The challenge is this: Record yourself completing the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge and post it to Facebook using the hashtag, or donate to the ALS Association. Then, nominate your friends.

Oakes was nominated by her father.

Before this, she says she had no idea what ALS was. She learned about the disease and decided to complete the challenge as a way to spread awareness about the disease.

“Being in college it was a little different because in my dorm room I don’t really have a bucket, I didn’t have ice,” Oakes says.

So, she improvised. She took a drawer from a plastic three-drawer organizational set and ice from a lounge fridge on her floor in the Barrett dorms. She says she was surprised by how large the challenge became.

“It’s shocking,” she says. “At first I was worried that people were doing it to get out of donating money, but to see the massive amounts of money that was being donated was fascinating.”

Indeed, the effects of this social media phenomenon created a great amount of change. Since the beginning of the Ice Bucket Challenge, the ALS Association has received more money than ever before.

“More than $15.5 million has been raised over the past month, compared to $1.6 million during the same time span last year,” according to an August article on wfmz.com

Since July 29, the ALS Association has received approximately $115 million in donations, according to the ALS Association’s website. Of these donations, the association has made an initial commitment of $21.7 million to expedite research for treatments and cures for ALS.

Oakes says she thinks this campaign was effective because it compelled people to do something through a constantly connective media.

“I think it’s appealing to us teenagers who are on Facebook all the time, I saw it ten times a day so I definitely think that made it bigger,” she says. “It’s definitely a way that gets my attention because those are the outlets I’m using. It’s super effective because otherwise I probably wouldn’t know what ALS was.”

But the campaign still has its flaws.

“I honestly wonder how many people, even people who gave money to it, knew very much about ALS after they did it,” Halavais says. “I would say that it was even more successful in terms of money than it was in terms of bringing about awareness in this case.”

Kwon says the ice bucket challenge confronted social media skeptics criticizing social media’s “slacktivist” culture.

“The success cannot be attributed singularly to the power of social media,” she writes in her email. “It was thanks to the power of creativity (wasn’t the idea interesting and fun enough to try it out?) and the power of celebrity involvement (aren’t we tempted to imitate the coolness of the reputed?) Social media happens to be an optimal delivery channel of these powerful components.”

#CelebrityStatus

It’s one thing to see your friends and family members dump ice water on their heads. It’s another thing to see celebrities do the same thing.

But the idea of celebrity takes on a different meaning when it comes to the Internet.

“For the ice bucket challenge in particular, you went from the C-list, to the B-list to the A-list, to Bill Gates and Obama,” Halavais says. “I think it’s interesting in terms of diffusion of the mean, you hit a lot of people when you hit celebrities. You hit people who have a large number of followers that can make it explode in a way it wouldn’t otherwise.”

Everyone from Hollywood-famous actors to Youtube-famous teenagers participate in various social media movements. Hill says this makes people across generational lines, pay attention to what is happening.

“It makes them stop and pay attention, and then it might touch them,” she says. Hill cites the “It Gets Better” campaign. The Youtube-focused movement sought to combat the high numbers of suicides in LGBT youth that often resulted from incessant bullying.

“You had everybody from Ellen to other celebrity gay activists as well as straight celebrities saying, ‘Hey, hang in there, your life will get better, don’t take yourself out’,” Hill says. “I think the fact that you had these celebrities in there, it got the attention of the young people who are struggling with this issue.”

Hill went on to say she thinks many people became aware of the dangers of gay-bashing and the psychology of young people because of this movement.

Celebrity participation in hashtag activism becomes a parallel with the psychology behind celebrity endorsements of products and services, which has been a prominent part of marketing culture for several years.

“They lend their credibility to the cause [and] it also gives the celebrity the opportunity to show their humanity and their connection to real people and real causes,” Hill says.

Halavais says that when celebrities get ahold of a movement’s message they can have a large impact in the message getting heard. He also says that they have the ability to change the message as well.

Actor Matt Damon added another layer to the ice bucket challenge by using toilet water in order to advocate for cleaner water worldwide, a cause Damon has supported for years.

Comedian Orlando Jones, an active member of the NRA and the Louisiana state police force, shifted the attention of the ice bucket challenge by pouring a bucket of bullet casings over his head. In the video, he supports the original message and says he will donate to the ALS Association.

However, he goes on to address the violence in Ferguson, Missouri. and calls for the abolishment of the “us versus them” mentality existing between citizens and police. The video has received nearly 2 million views and widespread attention across several media platforms.

Uter says celebrity participation plays a big part in the impact of a social media-based campaign.

“I feel you can do it without a celebrity but to have a celebrity you get a bigger voice and a wider audience,” he says. “It’s very integral if you want to create a huge movement.”

It is clear that each social media movement has its flaws. Is there a formula for the perfect campaign?

#LadderEffect

Halavais describes an ideal, social media-based campaign as a ladder.

“If you have 1 million people doing the ice bucket challenge and you’ve got 100,000 people giving money and you’ve got 10,000 people who actually get really interested in ALS and decide to volunteer some time in a campaign or decide to go into medical research at the most extreme end,” Halavais says. “Having a large number of people at the bottom of this is great, as long as you also have a ladder to higher degrees of participation.”

This facilitation is crucial to both a campaign’s success and the eventual change created in the cause. Halavais says that there are campaigns that focus on either the top rung or the bottom rung. He says the campaign needs to provide ways for people to get involved in a more complete way.

“The question is, are you using it in a way that encourages people to feel like they made a difference who haven’t,” Halavais says. “Do you have ways to step up people’s participation?”

He says campaign managers looking to use social media, need to be aware that not everyone will be willing to donate, or commit a weekend or most of their lives to the cause. So they need to have ways for everyone to participate in some way, even if it’s just dumping ice water over their head.

#ASUCLP

Uter and his classmates hope for the same effect.

He says he believes the use of social media in their campaign will not only encourage people to do something, but will also simply help them realize the intensity of the situation.

“Someone could be like, I know someone who was in that situation, I know that story, I can go to that and show the world that this is real,” Uter says. “That’s the whole point of it. Everyone is so disassociated from it and you have to be able to show people that this is in your backyard, that this is what’s happening everyday.”

It is apparent that Uter is deeply affected by his work with the project. This is not only because of what he’s learned pertaining to gender politics, but also because it reminds him of his family.

Uter says he doesn’t know what he would do if one of his sisters fell into an abusive relationship. He says it probably wouldn’t be good.

Durfee says that it made sense for students to want to use social media for the project, because “those are the roles they see themselves playing.”

The movement has begun.

So far, Uter’s group uses Facebook to share information and news surrounding abusive situations and other October events honoring Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

Another group of students running the Twitter account @ASUCLothesline branded their message with #ASUCLP. They spread the word and encouraged students to use the hashtag by writing statistics in blue chalk on sidewalks across campus. Their tweets contain statistics as well as reminders of the main event on Oct. 28-29.

On these days, clotheslines will display victim-made T-shirts on Hayden Lawn to drive home the message of the project. The group is also compelling the community to participate in a donation drive. On Oct. 29, the group will accept everything from clothes to cosmetics to cash. The donations will be brought to help victims of domestic violence at the Sojourner Center.

Uter says using social media as a tool for the campaign just made sense.

“It was kind of obvious for us because our generation, we’re so in tune and connected with each other,” Uter says. “Everyone else is going to different women’s shelters, let’s have a way to voice where they’re going, let’s be able to rreach more people than we’d usually be able to reach.”

#Blessed

Many professionals and fellow activists echo Uter’s optimism about social media’s effectiveness in activists’ campaigns.

Kwon says that social media has transformed mainstream cultural practice for the better.

“The fact that activist campaigns have recently become more ‘enjoyable,’ more ‘witty,’ more ‘clever,’ and more ‘trendy’ means that activism has become central to our cultural practices,” Kwon says. “I think the transformation of activism into mainstream cultural practice is advantageous to social activism in general because, under this cultural atmosphere, populations may be more prone to social changes.”

Durfee says that hashtag activism campaigns are essential for people dealing with situations similar to those discussed in her class.

“They are allowing people to empower each other and empower themselves in a way that I don’t think was possible before social media,” she says. “With a hashtag, it’s different than a Facebook or Instagram post because it connects people.”

Not only is the presence of social media becoming integral for social activism, it is also becoming a vital part of the way we communicate — something that shouldn’t be ignored, according to Durfee.

Durfee’s class found their inspiration in social media from watching a video about the emergence of the battered women’s movement, which started around kitchen tables.

“Our society isn’t like that anymore,” she says. “This [social media] is our kitchen, these are our tables.”

Durfee goes on to say that when she calls a co-worker on the phone, she apologizes.

“Phone calls are intrusive, but messaging, tweeting, Facebook-ing, that’s how we communicate with people now,” she says. “With this cyber-society, it’s interesting that we have a revolution and we’ve taken our social interactions online.”

Hill says that although it is sometimes for negative reasons, she is thankful for social media’s presence in our society.

“It can be annoying at times, you have to know when to shut it off,” she says. “But I’m happy that it’s there because it’s connecting such a vast country of 300 million people in a world of 7 billion souls in a way that we never have before.”

Whether it is for a combined cause or a simple one-on-one understanding, the key here is connection.

“Gutenberg changed what we know about the world because for the first time you had things written down, printed and distributed, you gave rise to the learned class that we have today,” Hill says. “Social media is profound because it’s bringing this huge planet together.”

Reach the writer at mamccrea@asu.edu or via Twitter @mmccreary6.