Listening to a man as jovial and uplifting as Sufjan Stevens tackle his depression is gut wrenching.

Stevens’s “Carrie & Lowell” is like a diary left open on a desk. You shouldn’t look; it’d be an invasion of privacy. But how can you resist? It’s there. It’s exposed. It’s begging for you to explore its harrowing contents.

With his first album since 2010’s grandiose electronic experiment, “The Age of Adz,” Stevens recalls the folk sentiments of 2004’s “Seven Swans,” but lathers on an impenetrable aura of melancholy.

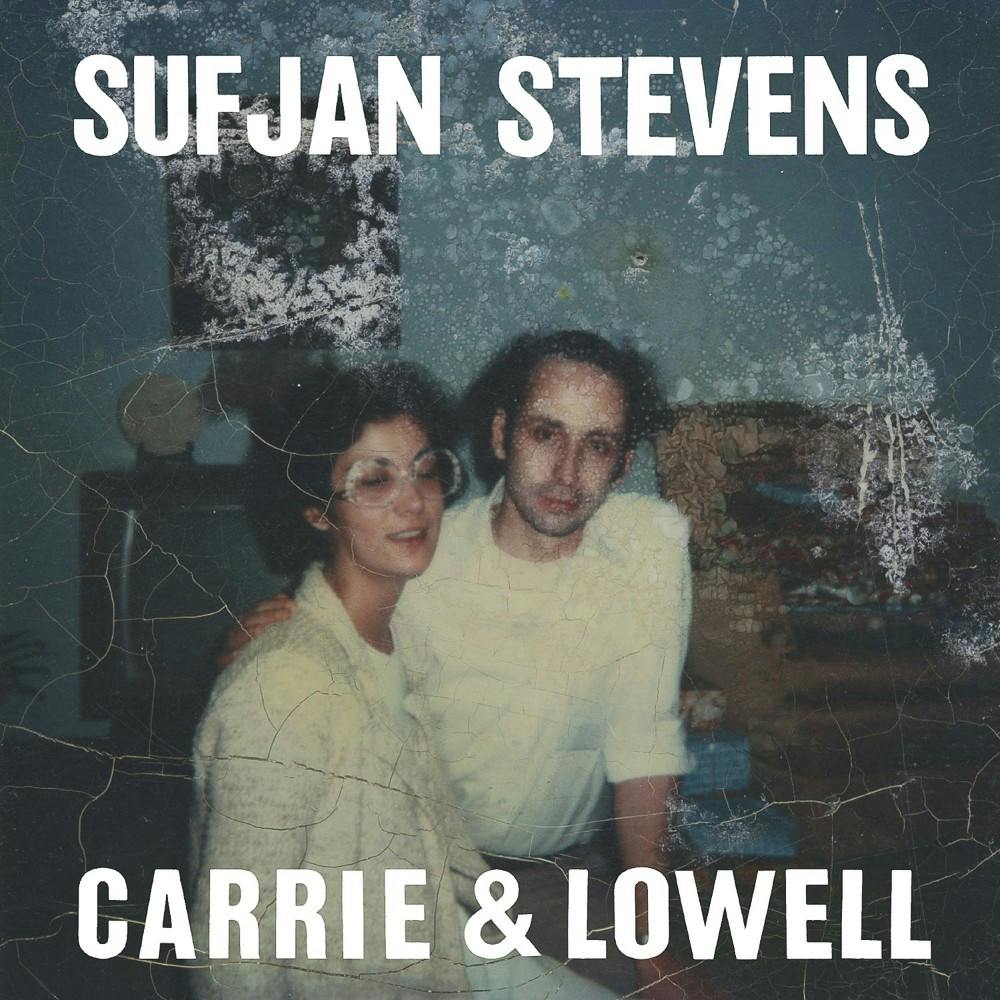

The album is titled after Stevens’s mother and stepfather. Carrie was bipolar and schizophrenic and suffered from drug addiction that left her often homeless. She abandoned Steven at a young age and remained scarcely involved in his life for years.

Carrie passed away of cancer in December 2012 — Steven reunited with her in those final moments. The opening track “Death With Dignity” has Stevens at a loss for words as he visits his dying mother in the hospital. “I don’t know where to begin,” he whispers over a plucking guitar.

Eventually he comes to terms with his mother’s struggles and sings, “I forgive you mother I can hear you, and I long to be near you.” He beats back his emotional scarring and lets her pass with solace.

There’s an authenticity in his lyricism few artists manage. “Carrie & Lowell” avoids the cryptic wordplay and forced complexity songwriters unknowingly suppress their messages with. Every phrase is clear in its meaning and better for it.

“Should Have Known Better” has Stevens directly pinning his depression on his mother’s neglect. “No, I’m not a go-getter. The demon had a spell on me.” Later in the song he regrets his inability to forgive sooner, singing “I should have known better. Nothing can be changed. The past is still the past.”

Every track has Stevens wrestling with conflicted feelings about Carrie’s death. “Fourth of July,” the album’s most somber moment, is a conversation with his mother about death’s inevitability. After trading terms of endearment, Carrie tells him that “we’re all gonna die.”

In a flash we hear anxiety in Stevens’s voice as he realizes a dreaded 40th birthday is approaching and becomes suddenly aware of his “fading supply.” As the song fades, he whispers inconsolably “We’re all gonna die,” repeating it until it sounds as if his falsetto is going to crack under the pressure.

Although gorgeous in context, the backing music in “Carrie & Lowell” serves only to caress Stevens’s confessions. Musically, this album is the antithesis to his the oft revered “Illinois.”

Stevens’s only real constant subject within his catalog is God, and he references his spirituality throughout the album.

“The Only Thing” is Stevens relying on God to relinquish his depression long enough to reconsider suicide. “Drawn to the Blood” has him pleading to God, asking why his constant prayer isn’t enough to douse the fires in his soul.

Every track is beautifully crafted and shines in its own right, but “John My Beloved” is on a pedestal above the rest. Realizing the love he thought he found is but a “fossil” with no life of its own, Stevens begs his lover to leave him and his “heart that offends.”

He knows he cannot maintain a steady relationship because he subconsciously searches for the mother’s affection he never had — a futile endeavor. Several times he mourns “there’s only a shadow of me; in a manner of speaking, I’m dead,” each repetition more painful than the last.

But it’s his final refrain that sears with pure lament. As he musters just enough strength to say it a final time, the music abruptly cuts out and fills with eerie silence until Stevens’s final breath comes and proves he can move listeners more in a single second then most artists can in their entire careers.

“Carrie & Lowell” isn’t an easy listen. It’s relentlessly haunting and devoid of catchy hooks or reasons to sing-a-long. Honestly, there are zero reasons to enjoy the album unless you’re a masochist.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t listen. “Carrie & Lowell” never feels like a piece of art. Instead, it exists as a looking glass into the mind of a consistently brilliant songwriter. Not a moment of it feels contrived and hearing Stevens’s attempts to reconcile with his mother will tug at heartstrings you never knew existed.

Reach the reporter at nlatona@asu.edu or follow @Bigtonemeaty on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.