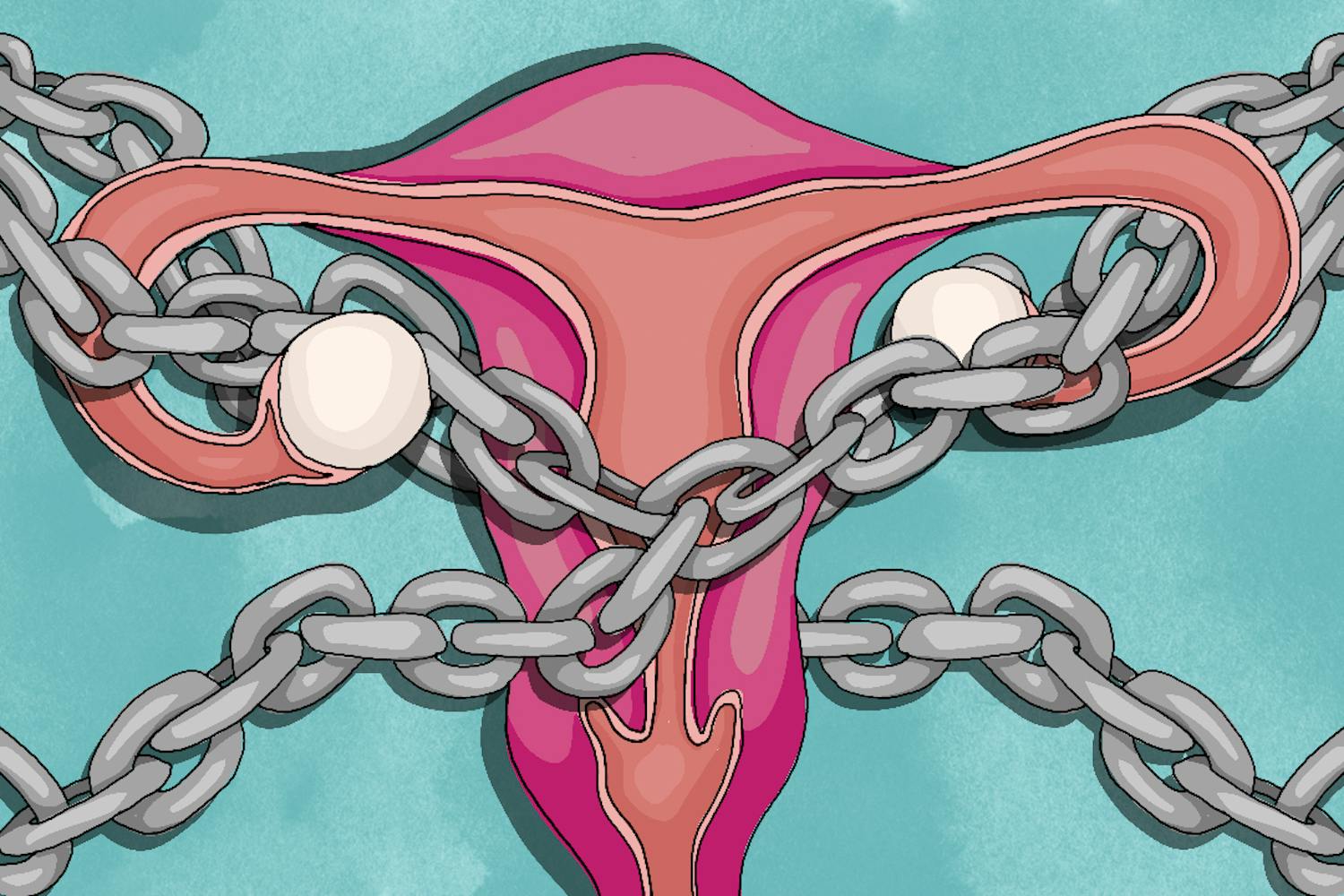

China’s controversial one-child policy was revoked this past week in favor of a two-child policy to be ratified in March. The previous one-child policy reported led to forced abortions, killing of female infants and under-reported female births.

Officials reported that this change was made because of an aging population and to boost the economy by creating a larger workforce with fresh blood. However, this shift to a two-child policy

Enacted more than 30 years ago, the one-child policy was intended to slow the booming population in the nation. While the policy’s effectiveness can be questioned, China’s current fertility rate currently rests at 1.66 births per woman, significantly lower than the peak of 6.16 births per woman in 1964 when the policy was enacted. However, in hand with this dropping birth rate came forced abortions, sterilizations and the selling of infants. Additionally, a traditional preference for sons led to a stark gender imbalance with there being 33 million more men than women in China as of 2014.

Much of the reduction of the birth rate in China happened before the introduction of the one-child policy in 1978. pic.twitter.com/zmOXSY4VUB

— Max Roser (@MaxCRoser) October 31, 2015

With the one-child policy, women in China often seen as being reduced to being numbers, objects or simply a way to gain a son. However, they also had an unprecedented increase in access to education and employment.

No longer trapped at home by multiple pregnancies, there was a growing number of women pursuing their master's degree and even their

While part of this is certainly due to social influences and changes within the nation, its impact expanded beyond fertility rates. Yes, the practice was unnecessarily harsh and cruel, especially in rural areas. However, it also sparked an increase in women’s education. Ironically, women had been working for decades to get the education they deserve in China, and the one-child policy served as a legal catalyst for their movement toward more education. With the two-child policy, women can achieve education and have autonomy over their reproductive choices.

With this change to a

Related Links:

One-child policy provides economic benefits, social disadvantages

Divorce in China remains among the lowest in the world, has great impact on children’s futures

Reach the columnist at mvandobb@asu.edu or follow @maureenvd on Twitter.

Editor’s note: The opinions presented in this column are the author’s and do not imply any endorsement from The State Press or its editors.

Want to join the conversation? Send an email to opiniondesk.statepress@gmail.com. Keep letters under 300 words and be sure to include your university affiliation. Anonymity will not be granted.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.