SPM writer Ryan Espinoza-Marcus climbs a tree with seven-year-old Brylee Russel and six-year-old Brynnly Marler at Tempe Beach Park.

SPM writer Ryan Espinoza-Marcus climbs a tree with seven-year-old Brylee Russel and six-year-old Brynnly Marler at Tempe Beach Park.Photo by Ana Ramirez

Our house is strewn with chaos. Spinning tops, stuffed animals, blocks and dolls sit idly in the living room. My parents' home office has been converted to a playroom, pink-walled and complete with dwarfish dining room furniture set for tea.

The girls are everywhere.

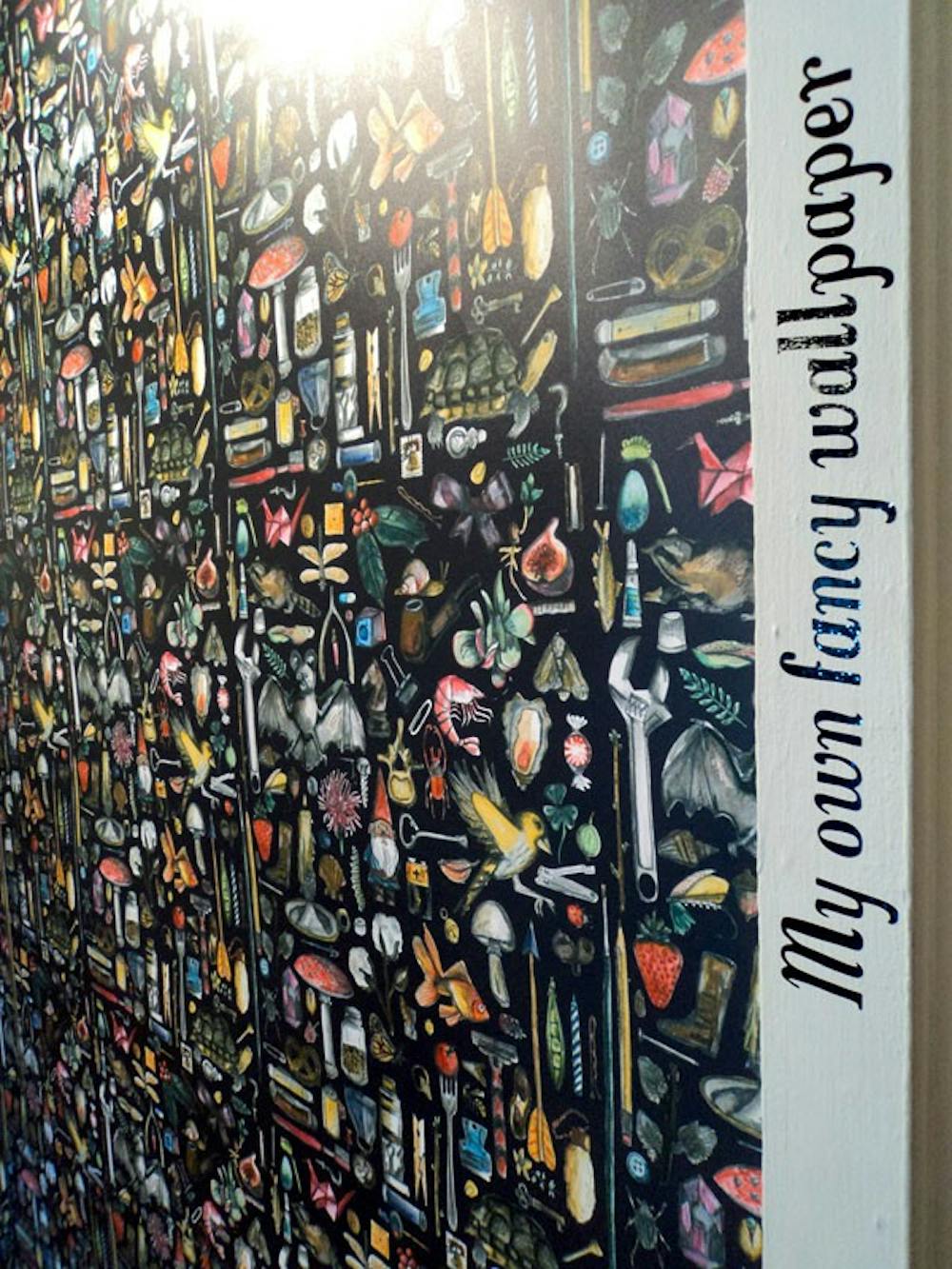

According to Espinoza-Marcus, children are totally different animals. Maybe monkeys?

According to Espinoza-Marcus, children are totally different animals. Maybe monkeys?Photo by Ana Ramirez

I have two sisters, aged two and four. Coming home for break is a shock. Children are creatures different entirely from my college-aged friends and peers.

They squawk in gated hallways, climb on the furniture, get into my socks when I fail to close my bedroom door. My former oasis is now a converted office and provides parking for tricycles, ride-on plastic airplanes, pink scooters and a large inflatable octopus. While the change irks me at times, having young siblings has grown me in ways I have trouble describing. I'll never have my room back, but watching my sisters and family grow is more comfort than any space could provide.

I remember when my first sister came home from the hospital. Her fingers were impossibly small. Her hands could barely grasp my finger. She could do nothing herself but cry.

I watched her sway and teeter on the living room rug as she took her first steps. I was a teenager then and took a strictly observational role in her development. I was apathetic to her charm. The baby was more an object of study than my sister, more a source of inconvenience than joy.

As hard as I tried to distance myself from the responsibility of helping raise my sister, I found it inescapable. Children are like sponges, soaking up information through examples set by those around them.

Espinoza-Marcus chats with five-year-old Faith Cordova as she fishes with her family at Tempe Beach Park.

Espinoza-Marcus chats with five-year-old Faith Cordova as she fishes with her family at Tempe Beach Park. Photo by Ana Ramirez

Adriella is my eldest baby sister. She is four years old now. Standing three feet tall, her hair is a burst of bouncy red curls. She speaks frantically in a questioning soprano and talks like a radio.

"What are you doing," she'll ask me, my nose in a book.

"I am reading a book," I'll say with a big, toothy smile.

"Why?"

"I like to read."

"Why?"

"It's nice to use your imagination some times. It can be relaxing and fun. Stories can be very interesting."

"Why?"

The barrage of 'whys' is endless. She reminds me of a philosophy professor, always questioning until her student has come to a place with no answer. She pimps me endlessly, looking for answers to questions I seldom consider. Though they are abstract and frustrating at times, I always try my best to answer completely. I am a trusted source of information to her, which is intimidating. At twenty years old, I am an authority on nothing, a fact of which she is entirely ignorant. When she comes to a question I cannot answer, I tell her honestly that I do not know before referring her to my dad.

Seven-year-old Brylee Russel and six-year-old Brynnly Marler follow Espinoza-Marcus' lead just as his younger sisters do back at home.

Seven-year-old Brylee Russel and six-year-old Brynnly Marler follow Espinoza-Marcus' lead just as his younger sisters do back at home. Photo by Ana Ramirez

My father is a physician at one of the country's premier research institutions. While I was failing high school algebra, he was in surgery implanting pacemakers to correct errant rhythms in his patients' hearts by day and writing research grants by night. He is a Stanford man, educated to the point of absurdity.

His training as a cardiac electrophysiologist ended when he was thirty-four years old. While working full-time as a doctor and parent, he completed a master's degree in epidemiology because he found the subject interesting and relevant to his research.

I was a teenaged miscreant, creating more problems than any baby could. I was a pathological liar and was arrested for stealing at sixteen.

My two-year-old sister is just learning to speak, her vocabulary a mixture of English and squawks. Before she is laid to bed, she has a ritual of bestowing goodnight kisses on each member of the family. After she kisses our parents goodnight perched in my father's arms, she is asked who is next.

"Rah rah," she will cry and waddle over to embrace me. She does not yet understand how kisses are given, pursing her lips and making tiny smacking sounds inches from my face. I recently spoke to my parents by phone, who told me that the ritual is still in place. In our living room hangs a number of family photographs, including a portrait of mine taken when I was seventeen. Every night, she requests to be carried to that picture to blow it a kiss goodnight.

To be an older brother is to be loved and respected unconditionally. They follow my example, gleefully imitating my actions and mannerisms. When I am home, they trail me through the house wanting to play or show me this and that. As a young man, I am used to earning my respect and affection, especially with women. My sisters have done well to remind me of the importance of family and the bond that runs through it.

Once a self-proclaimed pathological liar, now a brother with a sense of direction: Ryan Espinoza-Marcus.

Once a self-proclaimed pathological liar, now a brother with a sense of direction: Ryan Espinoza-Marcus. Photo by Ana Ramirez

When my first sister came home from the hospital, I knew that my home life would be different, but never expected such far-reaching change. Being an older brother has become a part of my identity.

When I first taught her to high-five at six months, I began to understand that I was tasked with teaching her no matter how stubbornly I resisted. For the rest of my life, I would be a teacher and example to her. I read as much as possible around the house. I want them to think reading is cool. For Christmas, I gave both of my sisters books and have resolved to bestow literature upon them as gifts for the rest of their lives. I'm buying them both copies of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in first grade. I want to read Oscar Wilde with them once they've entered college.

I never signed up to be a role model, a position for which I feel seldom qualified. The title of role model should be reserved for great men, wise men with titles like cardiac electrophyisiologist. Living in my father's shadow would be intimidating had he not taught me about the mensch, a Yiddish term for a person of integrity.

For all his degrees and experience, his lessons and teachings, the one he has most firmly impressed upon me is that a man's worth is measured not in intelligence or material wealth, but in virtue. His success is demonstrated by those he has mentored, his character defined by the example he sets for others.

Though I am no mensch, my sisters have provided me with a sense of direction in becoming one. I know that they will look to me for example throughout their lives regardless of my accomplishments or lack thereof, that they will trust and look up to their older brother simply because of my position in the family.

Many men have been lost on the serpentine path to virtue, which is riddled with traps and distractions. Whenever I feel lost, I need only look to the ground and follow my father's footsteps as I hope my sisters will be able to follow mine.

Reach the writer at rjespin@asu.edu or via Twitter @scotchandfoie