Video by Gabriel Sandler | Multimedia Reporter

Social work freshman Mark Ledingham said he remembers getting sick when he was roughly 8 years old. He never suspected his illnesses stemmed from cancer.

“In grade school, I used to black out," he said. "Other students would make fun of me."

He said his fingertips would go numb and the numbing sensation would move up his arms and into his face. Ledingham was forced to lie down during these spells and wait for them to pass.

He said the doctors told his parents that he was making up his illnesses for attention. Nobody could understand what the problem was. They all assumed he had migraines.

Ledingham said he remembers putting his head under a space heater in the summer to relieve some of the pain.

“I had a real tough time in school trying to retain new information,” he said.

The Diagnosis

In the summer of 1977, doctors at the University of Kentucky Medical Center detected a tumor in his brain. It was shortly before his thirteenth birthday, and he would later celebrate his birthday in the hospital.Ledingham said before they found the cancer, he had been sick on and off throughout the whole summer.

“My family doctor told me I had the flu,” he said. “Eventually, my left eye started to bulge out of its socket, and he advised my parents to take me to Lexington to the university hospital."

Ledingham said doctors performed a CAT scan and the prognosis was a brain tumor. They had to operate immediately.

“It was my first time in a hospital, so it was very scary for me and my family,” he said.

Lee, his mother, said it was hard for her to understand what was going on.

“They made me sign a paper that said I understood he might die,” she said.

Ledingham is the oldest of four children, and Lee said she remembers him being an energetic child with many friends.

“He had his own paper route and delivered newspapers to the whole town," she said.

Ledingham was diagnosed with cancer when technologies to detect early stages of cancer development were still limited.

According to the National Cancer Institute, in 1975, the U.S. annual incident rate of brain and other central nervous cancer was 5.9 for every 100,000 people. The annual mortality rate was 4.1 per every 100,000 cases.

In 2007, the incident rate was 6.4 cases for every 100,000 people. The higher incident rate is likely because of an improved ability to detect and diagnose brain cancers.

The Battle

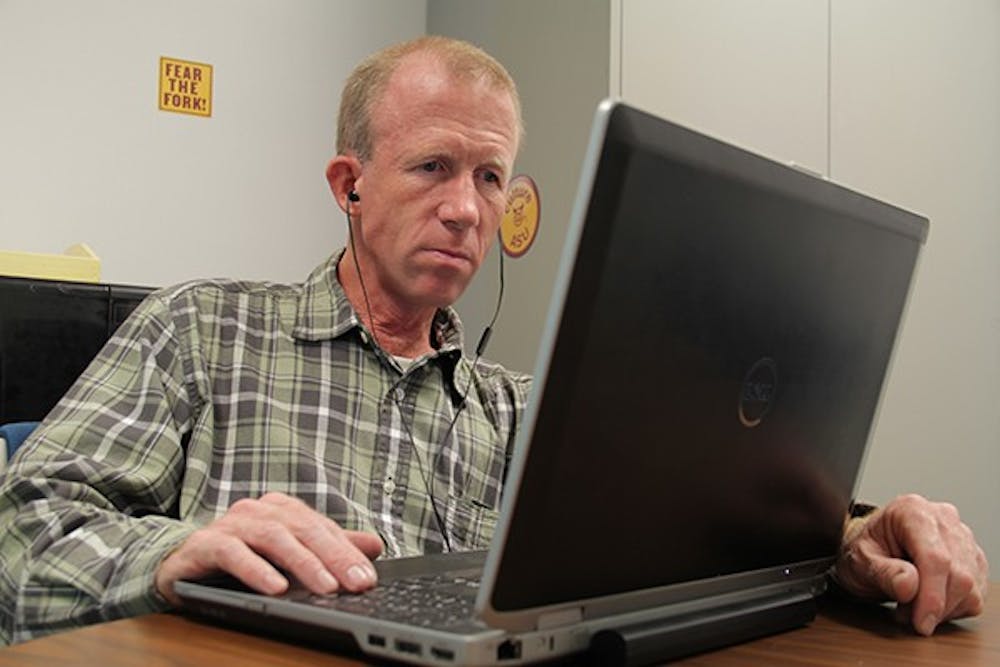

Social work freshman Mark Ledingham listens to the audio version of the novel “World War Z” for his class during his day off Friday afternoon at Discovery Hall. Diagnosed with brain cancer in 1977, Ledingham beat the disease but became legally blind as a result. (Photo by Shawn Raymundo)

Social work freshman Mark Ledingham listens to the audio version of the novel “World War Z” for his class during his day off Friday afternoon at Discovery Hall. Diagnosed with brain cancer in 1977, Ledingham beat the disease but became legally blind as a result. (Photo by Shawn Raymundo)Ledingham said he is not afraid of hospitals anymore.

“I’ve had brain surgery seven times now,” he said.

Ledingham said he didn't have any problems after his first surgery. The tumor itself was dissected and the prognosis was malignant glioma. It was sent to specialists on the East Coast who examined it through microscopes.

According to Genes and Development, malignant gliomas are the most common subtype of primary brain tumors. They are aggressive, highly invasive and are considered to be among the deadliest of cancers.

In its most aggressive manifestation, median survival rates range from nine to 12 months.

After the tumor was removed from Ledingham's brain, he immediately had to undergo a second surgery because he had developed gangrene in the hospital.

According to Human Diseases and Conditions, gangrene is a condition in which living tissue starts to die because blood flow to an area is blocked or bacteria starts to invade the body's tissue. Gangrene of the brain is uncommon but has been known to occur.

Ledingham said he started getting spiking fevers while in the hospital.

"The had me literally naked on ice with a fan blowing on me trying to get my fever down," he said.

Ledingham said doctors used a chemical in his brain to eliminate the gangrene, but it was too strong and left massive holes in his brain.

He said the surgery left him legally blind. He has no usable sight in his right eye and he has extremely limited sight in his left eye.

"Before the surgery, I had perfect vision and could have been a fighter pilot," he said.

Ledingham's vision was so impaired, he was no longer be able to ride a bike, one of his favorite things to do.

Ledingham said after the surgery, he drooled uncontrollably and his eyes slipped in opposite directions.

"One pupil was large and the other one was small," he said.

Ledingham said he didn't know who he was or why he was in the hospital, and it took him years to relearn everything.

Ledingham said neurologist Dr. Hillel Baldwin performed surgery on him in 1989 at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix to fix a shunt malfunction. Ledingham said after the operation, Baldwin looked baffled.

"Typically, a doctor doesn't sit down, they usually say, 'Have a seat,'" he said. "Well, he sat down and told me that I should either be dead or be a vegetable because of all the brain damage left from the chemicals used to combat gangrene."

Ledingham said Baldwin's words struck him.

"I don't know if I will ever forget those words," he said.

Ledingham has been tested for approximately 35 years for any sign the cancer will return.

"After 35 years, they said they wouldn't worry about it anymore, because I'm still alive," he said. "I'm alive, so I'm not complaining."

Ledingham said he recently had another surgery to fix another shunt malfunction.

According to the Beaumont Neuroscience Center of Excellence, a brain shunt is a narrow piece of tubing that is inserted into the brain. It relieves pressure in the brain by draining extra fluids to an area where it can be absorbed.

Every so often, a shunt will malfunction and will need to be replaced. Ledingham’s shunt lasted him 20 years before he had to undergo a shunt malfunction operation.

Ledingham said after that surgery, he had to relearn everything again.

“I didn’t know my way around my own house,” he said. “I didn’t even know I was in my house.”

His mother had to stay with him at his house until he was back on his feet again.

Moving Forward

Before the surgery, Ledingham had been attending Central Arizona College to get a degree in education.

“I wanted to help children with special needs,” he said. “But while I was there, a person in charge of placement said he was concerned about my focus on teaching special needs children since I myself am visually impaired."

School systems are not yet properly set up for visually impaired teachers, he said.

Ledingham said he met someone at the Disabilities Resource Center at ASU.

“She suggested I go into social work,” he said. “That way I could still go into a field where I could help people.”

Ledingham said he always felt helping people was a perfect fit for him.

Ledingham chose ASU because he would have access to more assistance for his limitations giving him the ability to achieve his goals, he said.

Journalism freshman Kelcie Johnson said she first met Ledingham in her sociology class.

“I was talking to him after class and he said he was struggling with the material,” she said. “Someone was already taking notes, but they weren’t really helping him, so I told him I would take more descriptive notes for him.”

Johnson said she meets with Ledingham after class and they talk about the discussions in class and go over the material.

Ledingham said he is often up all night studying.

“I do what I have to do,” he said.

Reach the reporter atkgrega@asu.eduor follow her on twitter @KelcieGrega