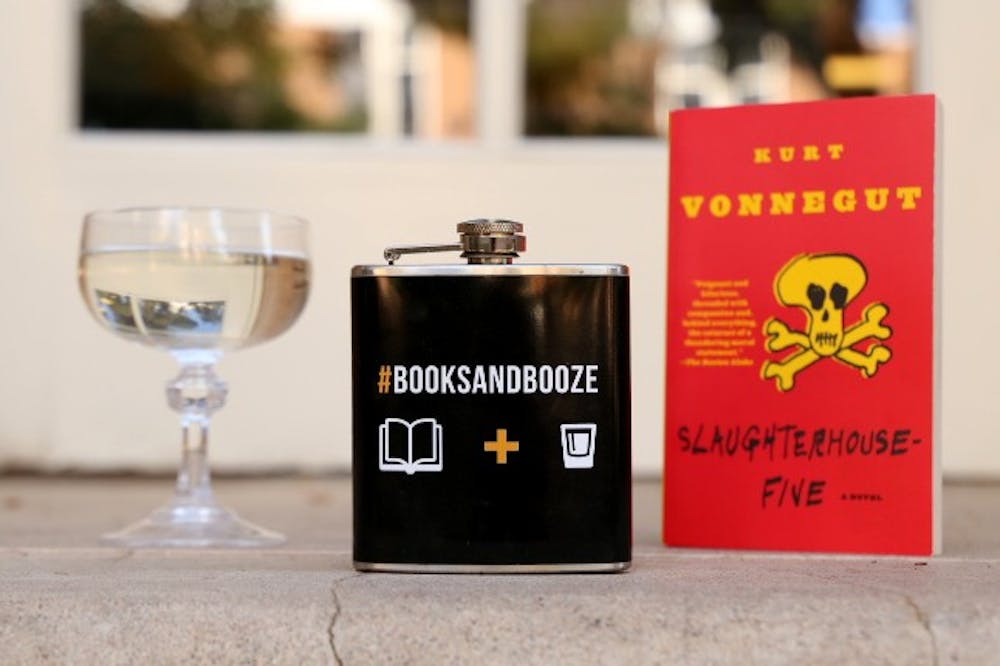

Each week reporter Carson Abernethy drinks his way through great works of literature, reviewing books and the booze that inspired them.

"Slaughterhouse-Five" is Kurt Vonnegut's best known book and one of the great works in anti-war and postmodern literature. It tells the story of a World War II soldier, Billy Pilgrim, who becomes unstuck in time. It blends Vonnegut's experiences in the war and the horrors of it, particularly the bombing of Dresden, with his typical mix of dark humor, science fiction and metafiction.

The martini is the pinnacle of cocktails, the standard to which all drinks are held. H.L. Mencken even went so far as to assert that the martini was "the only American invention as perfect as the sonnet." The martini is steeped in tradition and mystery, from the proportions of the drink, to how it's prepared, to even the number of olives used. Like "Slaughterhouse-Five" its simplicity belies incredible depth, and it's easy to get lost in both of them.

Recipe

4 oz. gin

1 oz. dry vermouth

cocktail glass, preferably a champagne coupe

Combine gin and vermouth over ice. Stir well, and strain into chilled glass. Garnish with a lemon peel or olives (while some may say even-numbered olives are a faux pas, two seems to be the best, as Sinatra reportedly recommended — one for you and one for the girl who just walked in the door).

And in regard to that eternal question:

Sorry, James, the answer is always stirred (and just so we're clear, a vodka martini is no martini at all).

Prose: 4.5/5

The prose of "Slaughterhouse-Five" is clean and uncluttered, but also imbued with a great amount of wit and humor. Vonnegut even includes drawings, though to a lesser extent than in other novels, which enhance the prose in very interesting ways. The sentences in the novel are simple, never really ornate, but still possess a deepness of meaning. Vonnegut recognized more than most that writing is communicating and that you could convey complex subjects in a way that is understandable to most everybody without sacrificing content.

Characterization: 3.5/5

The novel has many interesting figures, many of whom fans of Vonnegut will recognize, as in the case of Kilgore Trout and Eliot Rosewater, who appear in other Vonnegut novels as main characters. Billy Pilgrim, the novel's main character, is a WWII soldier who becomes unstuck in time and travels in time sporadically throughout his life, witnessing events past and future. This character is an interesting study on the effects of war and PTSD, mixed with science fiction themes, like time travel and alien encounters.

Cohesiveness: 4.5/5

The structure of the novel perfectly mimics the experience Billy has of being unstuck in time — it drifts forward and backward in a very non-linear fashion, and it ends with time traveling back to the beginning. One of the more interesting aspects is the layer of metafiction spun throughout the novel; chapter one begins with the famous line, "All this happened, more or less," and a first person narrator who explains their connection to the events of the novel in what seems an author's preface, before segueing in chapter two to Billy's story. This narrator even appears later in the work, in Dresden. In a typical postmodern way, it manipulates the correlation between fiction and reality, while poking fun at both.

Relevance: 5/5

War of course is a perennial topic and its abolition a common goal. Vonnegut brilliantly addresses the idea of war and anti-war throughout the novel, in a way that is incredibly relevant today. There's that brilliant exchange between the author and Harrison Starr in which the author says he's writing an anti-war book, and Starr responds by asking why he doesn't just write an anti-glacier one instead. Starr is arguing that there will always be war, and if not war, then there will always be death. The brilliance of this work is Vonnegut's both acceptance and rejection of this — his use of humor in the face of tragedy creates a buffer from it. He argues there's nothing intelligent to say about a massacre, but the very act of writing an intelligent novel seems to override that and accomplish that it is always possible to draw meaning from something, even when it is not apparent.

Overall: 4.75/5

"Slaughterhouse-Five" deals brilliantly in contrasts, balancing tragedy with satire and life with death. Vonnegut understood the importance of humor in creating a respite from life's pitfalls and how many issues can really only be talked about meaningfully if they are talked about humorously. Vonnegut possessed one of the greatest voices in post-war America, and this novel is a testament to how earnestly and faithfully he captured the frailty, but also the durability, of the human condition.

Related links:

Books & Booze: 'Norwegian Wood' by Haruki Murakami

Books & Booze: 'Wuthering Heights' by Emily Bronte

Reach the reporter at cabernet@asu.edu or follow @ccabernethy on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.