ASU’s collaboration with the Mayo Clinic is working to create a positive impact on cancer treatment, according to a physics researcher at the university.

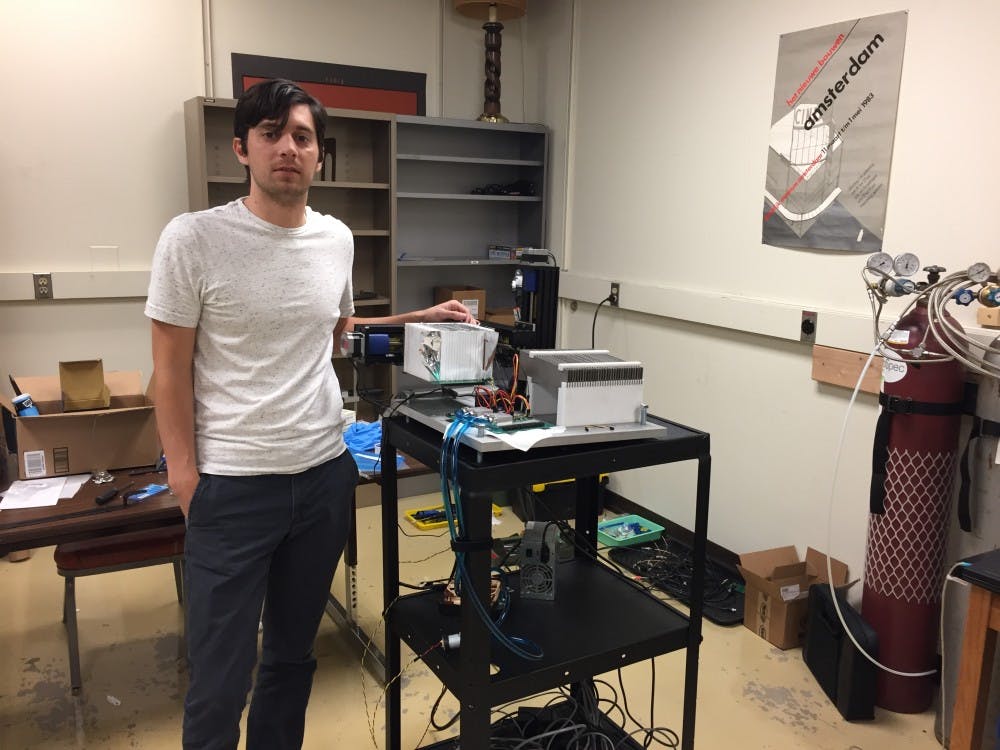

Jason Holmes, a postdoc physics researcher at ASU, said he is designing three proton beam therapy-related devices that should help the process become more accurate and therefore safer for the patient.

“The less radiation you get, the less sick you’ll be in the short term,” Holmes said. “And in the long term, you’ll be less likely to get other cancer, other tumors.”

X-rays comprise most radiation therapy, but they permeate the patient’s entire body which damages cells before and after the tumor, unlike protons which stop inside the tumor, sparing the cells positioned behind, Holmes said.

Holmes said he hopes his devices will solve two key limitations with proton beam therapy: knowing where the protons stop, and knowing how many go into the patient’s body.

Current methods can only predict the range of a proton within a centimeter, Holmes said.

“You can’t really use this to help the patient, to help their outcomes, until you get within around a millimeter,” Holmes said, referring to the proposed accuracy of his range detector.

Another one of his prototype devices attempts to count the protons introduced to the patient by first shooting them through a diamond.

“I’m literally talking about ‘there goes one proton, then another, there’s another,’” Holmes said.

Once these two problems are taken care of, proton beam therapy ought to be safer, he said.

“If you know how much energy is being deposited into a patient, and where it is being deposited, then you know basically everything you need to know,” Holmes said. “That’s what all of our projects are trying to do.”

Ricardo Alarcon, the Principal Investigator for all three devices and Holmes’ adviser, said the range detector’s speed will be a first for the field.

"It'll be the first time we will be doing this therapy and will be actually looking at what is happening while the treatment is being conducted,” Alarcon said.

The Mayo Clinic’s proton beam delivers the subatomic particles in spans of 5 milliseconds, so they want responses just as fast, he said.

"The whole idea started because Mayo Clinic decided to build a proton therapy clinic in Phoenix, and there are only a few in the country,” Alarcon said.

He said Holmes’ progress on his research has been impressive.

"It's a really unique position for the student to be in ... thinking of the problem, building the apparatus that is going to solve that problem, and then going and doing the experiments,” Alarcon said. “And that's what he's doing."

Alarcon said the project has been rewarding for both Holmes and himself.

"From an educational point of view, that is extremely satisfying for me," he said.

Martin Bues, the lead proton physicist for the Mayo Clinic’s radiation oncology department who fosters the collaboration between the ASU physics department and Mayo Clinic, said the research is satisfying for different reasons.

“The beauty of Jason’s device, if it in fact works, is that all uncertainty will be removed because his device will actually measure in real time, in living breathing patients, where the beam stops,” Bues said.

Of course, not all uncertainty will be removed. As Holmes said, there will still be a millimeter of uncertainty.

Bues said reducing this uncertainty should reduce the patient’s discomfort.

“The less we irradiate healthy tissue, the fewer the unwanted side-effects of the radiation will be,” Bues

Although Bues considers proton beam therapy safer than X-ray therapy, these side-effects can range from bone fractures, to visual impairment and neurological problems, depending on the type of cancer treated.

“In order to use proton beam therapy to the fullest, we need to know with the highest possible precision where the beam will stop,” Bues said.

Reach the reporter at chawk3@asu.edu or @coreyhawkJMC.

Like State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.