With dozens of bars and restaurants, shopping and nearly 50,000 students within walking distance, Tempe's Mill Avenue just might be Arizona's most dynamic stretch of pavement.

People come to Mill Avenue for a number of reasons, but one stands out. They want to drink.

And that creates problems. Underage drinkers routinely get into bars, and over-served drinkers often cause anything from bar fights to car accidents.

Trying to keep up with the problems is an understaffed Arizona Department of Liquor, whose agents must enforce the state's liquor laws.They're fighting an uphill battle.

Regulating chaos

There are approximately 9,300 active liquor licenses in Arizona, and the Department of Liquor is responsible for all of them.

And at any given time, only 14 investigators in the department are responsible for making sure that all the licensees are following the rules. There's a slew of bars and restaurants on Mill Avenue alone that are under the supervision of the Department of Liquor.

"We are stretched to cover even basic enforcement," said Myron Musfeldt, acting director of the Department of Liquor. "And with budgetary constraints, that won't change anytime soon."

Musfeldt said that the department should have 24 investigators, but the money just isn't in the state's budget.

He said that the 2002 budget is about $2.45 million, a 4.5 percent cut from the 2001 budget. The Department of Liquor gets the vast majority of its revenue from licensing fees and transactions, while a small amount comes from violation fines.

"We are very dependent upon other agencies," Musfeldt said. "We rely a lot on local law enforcement and we're not large enough to do large events on our own. We work closely with ASU and Tempe police to give adequate service."

While the Department of Liquor is routinely challenged to provide adequate enforcement with a thin staff of investigators, it has still handed down more than $30,000 in fines to Mill Avenue establishments since 1997. Thousands of dollars more have been fined from drinking establishments in Tucson and Flagstaff, the homes of UA and NAU, respectively. Because of the small number of investigators, areas outside the Valley rarely receive the same level of supervision as areas close to Phoenix.

The department has two primary functions, administrative and criminal. While the administrative arm of the department hands down violations and levies fines, the criminal branch cites establishments and arrests patrons for violating liquor laws.

Although the Department of Liquor is ultimately responsible for enforcing the state's liquor laws, police often take care of most local enforcement. Police have a lot more manpower than the Department of Liquor.

The department hunts down violators by acting on complaints and performing random checks. Most of the work is done undercover with employees unaware that a department official has become just another patron.

Jesus Altamirano, a lieutenant in the Department of Liquor's Community Interaction Unit, said in the past two years approximately 30 licenses have been revoked statewide. He said Mill Avenue continues to be an area that garners a lot of attention.

"We'll get complaints from citizens, local police or neighborhood or merchant associations, and then undercover agents will be sent there," Altamirano said.

He said the two most common complaints involve over-service and underage drinking.

"Underage drinking has become more prevalent because (fake) IDs have become very good in the past few years," Altamirano said. "Some even fool the machines and people often are using their own picture."

Altamirano, an eight-year veteran of the department who did undercover work early in his career, said, although investigators are trained to discern fake IDs, it's getting more and more difficult.

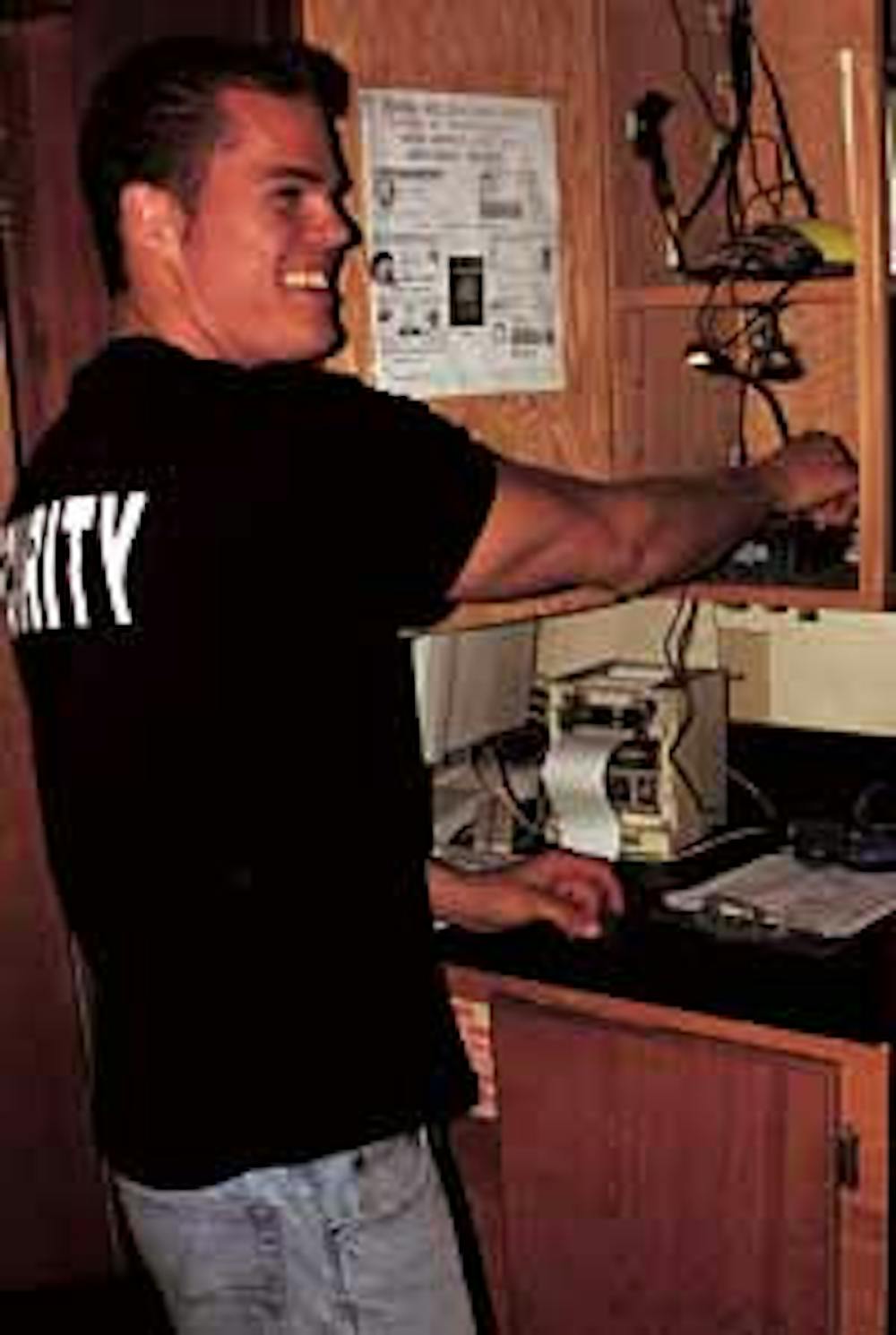

Bars and restaurants along Mill Avenue generally use electronic scanners, or cameras that take pictures of every ID checked. Doormen are still responsible for operating these machines and detecting fakes when IDs trick the machines.

If people, typically ASU students who have yet to turn 21 years old, make it into a Mill Avenue bar or restaurant using a fake ID, undercover investigators may be waiting for them.

"We'll start looking for young-looking kids and we'll actually start talking to them," Altamirano said. "We'll arrest underage people and typically fine them $300 to $800. Then they have a criminal record.

"If there is negligence on the bar's part, those running the bar can also be arrested," he said. "We go after the person on the liquor license."

Underage drinkers aren't the only group of violators hunted by the Department of Liquor investigators. There are much more obvious offenders.

"If people are falling asleep or falling over, it's pretty obvious that a reasonable person would know they have been over-served," Altamirano said.

He said that for establishments and/or patrons to be cited for over-service, a person must remain in the place for at least 30 minutes. That time is designed for employees to notice if that person is clearly drunk and remove him or her from the establishment. No such time frame is necessary to arrest underage drinkers.

Securing the fort

For restaurant or bar managers on Mill Avenue, alcohol consumption in their establishment is a top concern. There's a simple reason for this: breaking liquor laws costs money.

Since 1997, more than $30,000 in fines has been handed down by the Department of Liquor to bars and restaurants on Mill Avenue. The fine money goes into the state's general fund. Thirty-thousand dollars is a conservative estimate because of places that have since moved from the area or closed.

Topping the list with $6,500 in fines since 1997 is Saki's Pacific Rim Café & Sushi Bar at 740 S. Mill Ave. The restaurant has had seven violations relating to liquor, six of them involving underage drinkers.

Greg Snodgrass, the 27-year old general manager at Saki's, made sure to point out that the restaurant hasn't had a violation in more than a year. The last violation, March 30, 2001, cost Saki's $3,000 for allowing an underage person to be given alcohol and having an underage person on the premises without a parent.

"The Liquor Board was very close to revoking our liquor license for three days," Snodgrass said.

Altamirano said it usually takes four or five of the same violation to shut a place down — and that's all after discussions with licensees and fines against the establishment.

"Alcohol is a regulated and taxed industry," he said. "Many establishments are very responsible, but other places let anything and everything happen."

After what were the sixth and seventh violations since June 1998, changes had to be made at Saki's.

"After that we got rid of our electronic ID swiper and got a camera put in that records every ID we check," he said. Snodgrass also said the restaurant hired a far better doorman to work busy nights.

Electronic devices that scan magnetic strips have become commonplace in bars on Mill Avenue over the past year or so, but they are far from perfect.

"Swiping is a great system, but for it to work there has to be a magnetic strip on the ID," Snodgrass said. If the ID doesn't have a magnetic strip, the decision lies with the doorman.

The Owl's Nest at 501 S. Mill Ave. uses both scanners and a camera. Dave Corba, the bar's manager, agrees that the scanning device is generally effective.

"We've been using the machine for about a year, and used in the right way they are very effective," Corba said. "There are ways to get around it, but people are less likely to try using a fake ID here in the first place because of the swiper."

Owl's Nest has had only one violation since 1997. In May 2001 the bar was fined $375 for having an underage person on the premises without a parent. Corba said the bar will serve about 400 to 500 people on busy nights and confiscates anywhere from 10 to 40 fake IDs a week.

Corba and Snodgrass agree that it's impossible to keep every underage person out of bars all the time and that one particular type of fake ID is the most effective. Doormen sometimes run into state-issued IDs with false information on them.

"People will go to the MVD (the Arizona Motor Vehicle Division) and get an official state ID with their own picture on it," Snodgrass said. "That's the toughest way to catch people, but we're still responsible for doing so."

Guarding the gate

"Every bar (on Mill Avenue) every night has underage people in it," Snodgrass said.

While those under 21 face the prospect of hundreds of dollars in fines and a DUI if they get behind the wheel, there is no lack of underage people doing anything they can to get a drink on Mill Avenue.

"We've taken more than 230 IDs since August," Snodgrass said. "We usually take seven or eight IDs on busy nights."

Since 1997, of 19 bars and restaurants on Mill Avenue, 37 of the 59 liquor violations have been related to underage drinking.

"Kids aren't wise drinkers," Corba said. "With all the liquors and energy drinks out there, younger drinkers have a lot more problems."

For doormen along Mill Avenue, catching people trying to use fake IDs is their biggest challenge. Ben Johnson, the 22-year old doorman at Owl's Nest, knows a thing or two about fake IDs — he used to make them.

He said it was a few years ago when he was living in a different state, but he has seen just about every way to falsify an ID. But finding a flaw on the ID is only half the battle.

"It's really more about confidence and mannerisms," he said. "Nervous people will be a little jittery and try to be all buddy-buddy with me by asking me a lot of questions."

Owl's Nest hasn't had nearly the amount of problems Saki's has in the past few years, but since Snodgrass hired Quinn Foster, the problems have stopped. Foster, an ASU bachelor of interdisciplinary studies senior and former ASU wrestler, doesn't have to try hard to intimidate would-be underage drinkers.

All he has to do is ask a question or two.

"I'll ask girls if they are using a fake, and some of them just start shaking," he said. "I'll say the name on the ID and some people don't look up, then you know it's not theirs."

People can fake their mannerisms, but if they are using the real ID of a different person, they can't fake genetics.

"You have to look at the height, weight and facial features," Foster said. "People all have different noses and cheekbones."

Despite his muscular stature, some people still like to give Foster a hard time.

"Damn near everybody asks for it back when I take it," he said. "They get a little hot. Some people definitely want to fight."

Bars and restaurants routinely keep the IDs they take to train employees how to recognize a fake.

In the trenches

While the Department of Liquor relies mostly on undercover work, it's the police who stare drinking-related problems in the face, night in, night out.

Noah Johnson, a Tempe police sergeant and supervisor of the city's Bike Squad, said the Tempe police have a great relationship with the Department of Liquor, but by nature the police are a much more visible presence when it comes to enforcing drinking laws.

He said over-service is the squad's biggest challenge.

"It's hard in an area like Mill Avenue to put the blame on one bar because it's hard to tell who over-serves them," he said. "But over-service becomes the root of a lot of assaults, fights and DUIs. Most people we arrest are doing things they would never imagine doing sober."

The Bike Squad patrols the downtown beat from College Avenue to Ash Avenue, and University Drive to Tempe Town Lake.

"We patrol heavily along Mill Avenue and from time to time go into bars," Johnson said. "Most of our activity is pro-active, we are always looking for things."

Johnson said the average weekend night usually produces six to 10 alcohol-related arrests, and the most common offense is drinking in public or having an open container in public. Fake IDs rank as the No. 2 offense.

But beyond the common offenses, Johnson has seen some uniquely disturbing things in just more than a year as part of the bike squad.

"The strangest thing I've seen was six or seven guys riding down the street on their bicycles naked," he said.

Not all offenses are as humorous.

"Almost every night we see people with open containers in cars," he said. "Because of our vantage point on the bikes, we can look right into cars. People don't expect to be pulled over by an officer on a bike, but it happens."

"You're really taking a chance drinking on Mill Avenue because there are people waiting to catch you," Johnson said. "You're rolling the dice."

Different places, same booze

Restaurant chains and trendy shops may have taken the place of biker bars over the years in downtown Tempe, but the fact remains: People from all over the Valley, plus thousands of ASU students, still head to Mill Avenue if they want a drink.

"It (Mill Avenue) is a lot more corporate than it used to be," Musfeldt said. "The small-town feel has disappeared."

Musfeldt has worked in the Department of Liquor for 22 years. The drinking age was only 19 when he started.

"But as far as we're concerned, the problems remain the same," he said. "College towns are going to have their problems."

While the Valley and ASU have exploded with growth in the past few decades, Mill Avenue has adapted. And while some problems endure, others don't.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s cruising was the area's top concern. Today it's not a worry.

"Gridlock was our biggest problem, but the cruising law passed in the early '90s solved that problem," Johnson said. "The cruisers were mostly high school kids, but it (the cruising law) minimized a lot of the underage drinkers that were in the area."

Cruising might be under better control, but with the influx of more freshmen at ASU and advancing computer technology used to produce fake IDs, plenty of underage drinkers still frequent Mill Avenue bars.

To combat the problem of underage drinkers, liquor licensees are being more and more careful.

"The biggest change I've seen over the years is that we are getting a more professional type of applicant," Altamirano said. He added that many of the liquor licensees on Mill Avenue have locations in other states and understand the consequences of violations.

"Mill Avenue in the last five years has progressively been getting better and better," Altamirano said. "Retailers have been improving, but that doesn't mean there won't be violators this weekend."

Reach the reporter at jtreered@aol.com.