The day starts at 7 a.m.

President Michael Crow has a quick chat with student government leaders Brian Collier and Brandon Goad, which makes him late for the three-hour science, technology and public affairs class he teaches on Main campus once a week. He arrives in a flurry of black pants, blue shirt and red and blue tie. His golden brown eyes are bright and alert, despite the bags beneath them.

He cracks jokes and tells stories of his exploits, including one about hopping on a helicopter to explore the inside of a volcano. After a few minutes of casual chatter, he gets down to business. The students are alert as Crow moves easily from topic to topic, pulling numbers off the top of his head and speaking without notes. He never seems to stop moving -- or talking -- except to sip from a Diet Coke he won't finish.

After a couple of hours, he excuses himself early to meet with Phoenix Mayor Phil Gordon. On his way back to campus, he calls his office to order a turkey sandwich, which he scarfs down before meetings with Jorge de los Santos, ASU's Director of Pan-American Initiatives, and Jonathan Fink, vice president of Research and Economic Affairs, during which he will drink half of another Diet Coke because, he says, coffee makes him too jittery.

Then it's off to another appointment. This time, he spends it speed walking with Dean of Education Eugene Garcia, talking about financial aid to graduate students, and at the same time inspecting the progress of the new ASU Foundation building on University Drive. On the return trip, he greets students with friendly smiles and nods and picks up a cracker wrapper that someone has thrown on the ground. He drops the wrapper in the trash without pausing.

The afternoon is packed with more meetings, including one about selecting the new business school dean. At 5:30 p.m. he sits on a panel to field questions about a proposed tuition hike, and it's 8:30 p.m. before he slows down.

This is one day in the life of ASU President Michael Crow, who makes $468,394 a year to run

Arizona's largest university. Since arriving at ASU in the fall of 2002, Crow has raised ASU undergraduate tuition by more than $1,500, garnered more than $100 million in gifts from private donors, reorganized the University and been thrown out of the office of Gov. Janet Napolitano.

And that's the short list.

Almost no one is neutral about this man who has upset nearly every sacrosanct institution at a place where change has traditionally come slowly, if at all. They know him as a man hell-bent on change and impatient with those who aren't. They note the searing looks and acerbic comments, often accompanied by a little expressive eye rolling, that he shoots at people when he doesn't think they know what they're talking about. People on campus think of him as a force of nature, a no-holds-barred, take-no-prisoners whirlwind of ideas and directives.

They respect him, fear him, like him and despise him--often all at once.

Crow knows this is the way some people--maybe most people--see him. But it isn't the way he sees himself. In many ways, Crow still thinks of himself as the kid from a big family who attended four different mediocre high schools and was lucky to go to a state college; the guy who couldn't decide on a major because he was interested in everything; the geeky dorm rat who practically lived in the library and rarely dated.

COLLEGE?

Crow didn't think about college until his senior year of high school, having spent much of his time dabbling in sports and playing strategy games, such as five-dimensional chess, with his buddies. He applied late to the University of Illinois, Iowa State University, the University of Wisconsin and the Air Force Academy. His father, a Navy man without much money, wanted him to go to the Air Force Academy because he wouldn't have to pay for it.

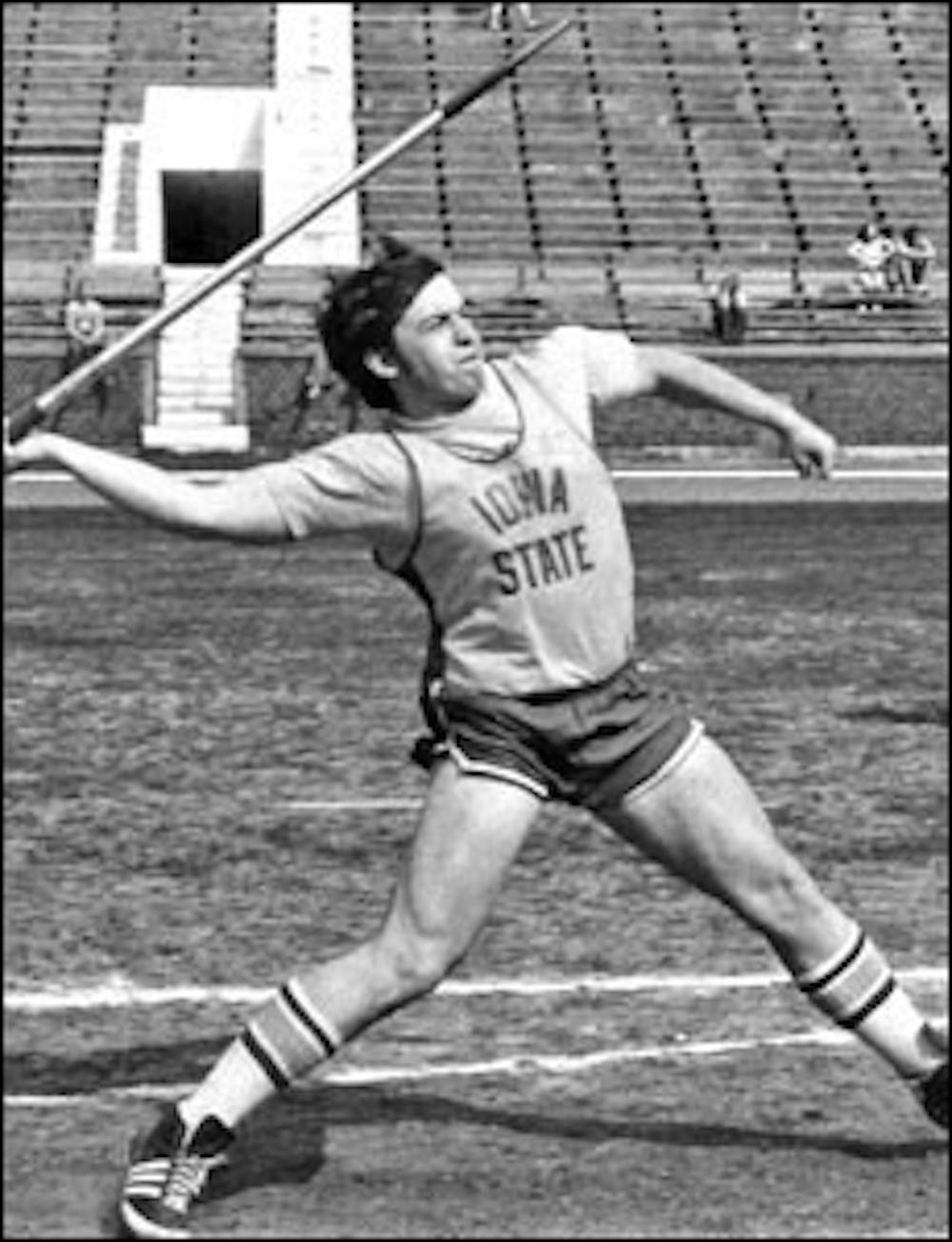

Although Crow was accepted, he says he wanted more flexibility. In the end, he chose Iowa State because the track coach wanted him to come and throw the javelin. He attended on a partial track scholarship with a small stipend for food and officially became an Iowa State Cyclone.

He was the first Crow to attend college since the 1840s.

DORM RAT

Once he moved onto the leafy, grassy Ames, Iowa campus, Crow became a dorm rat. While other college guys lived in fraternity houses or shared a place with friends, Crow lived in the dorms all four years, working as a resident assistant to pay for room and board. He lived on campus, spending almost every minute there.

In the Crow household, there were never many books around--"too expensive"--so when he got to school, one of his first stops was the library. "I remember going to the library and asking, 'How much of this can I use?' and the librarian said, 'All of it.' I developed a strategy to try and read or look through one book from every section of the library to see what it was about and how the library worked."

He lived in the library, surviving off whatever he could find in the vending machine and devouring books by the stack. Despite being a voracious reader, Crow says he couldn't write well. "Most of the high schools I went to were crummy," he says. So he divided his studying time between the library and the campus writing center, where he devoted hours to learning how to write an essay.

"College was a chance to stabilize," he says. "It was my one shot at education."

His appetite for learning carried over to his classes. Crow never really chose a major, but took as many classes as he could in a wide variety of subjects. He would take classes ranging from philosophy to water management. "I wanted to major in five things," he says. "I was kind of a nut."

Crow says he was in the honors program at Iowa, but dropped out because he was too busy with government and sports. When it came time for graduation, he just happened to have the most credits in political science and environmental studies so that's what he got his degrees in. He graduated with a GPA of 3.4.

While at Iowa State, Crow served as a student senator and worked as a liaison to the Iowa Legislature. He also worked as a research assistant for Jim Gulliford, a graduate student, investigating the environmental impact of coal extraction. Gulliford, 53, now works as a regional administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency in Kansas City. He says he and Crow both worked and "looked for opportunities to learn."

"Michael was--is--a high-capacity individual," Gulliford says. "I worked hard to keep up with and ahead of him, and to challenge him."

WEIGHT MAN

When he wasn't studying, Crow was on the field with the track team, throwing a javelin. Although he wasn't a gifted athlete, he was competitive. And because his sport required brawn, he was a "weight man" and had to keep up his calories. He and other team members would go out for pizza, each devouring a 16-inch, double-cheese, double-pepperoni pizza.

He knew a lot of different kinds of people, but he was definitely not a cool-guy, frat-boy partier, Crow says. He couldn't afford to join a fraternity, rarely drank and never used drugs. "I could get along with almost anybody," he says. "I had no hugely moralistic view of the world. I didn't look down on people who drank, but I did look down on people who used drugs."

Instead of parties, Crow would go to movies--nearly 10 per month. He also remembers watching "Saturday Night Live" with a room full of laughing classmates, "back when 'Saturday Night Live' was funny."

Gulliford says neither he nor Crow dated very much. "He didn't circulate with a large number of people. His was a pretty small circle of friends."

Crow was popular within the circle and with the faculty, but his self-confidence and intelligence could be intimidating, Gulliford says. "Like a lot of people, he expects performance ... he expects results," he says, "but he did not belittle or ridicule."

During the summer, Crow would lead backpacking trips to Montana, Wyoming and Colorado and canoe trips to Minnesota and Canada. The physical challenge helped him to become a whole person physically and mentally, he says. When it came time to graduate, Crow still didn't find the opportunity to do much celebrating.

Instead, he went to the funeral of his best friend from high school, who had been killed in a drunken-driving accident. While they were still in high school, Crow says, the two of them signed a pact to never drink and drive. But his friend and the driver of the car had both been drinking the night of the accident. "So not much celebration," Crow says.

FINDING HIS NICHE

As a young college student, Crow says he thought about how he wanted to contribute to the world and decided that his passion was education and learning. So after college, Crow enrolled in the Maxwell School at Syracuse University in New York, where he earned his Ph.D. in public administration. From there, he worked his way through associate professorships, directorships, full professorships and finally to vice provost at Columbia University.

In 2002 he was inaugurated as one of the highest paid university presidents in the country--a far cry from the nerdy dorm rat at ISU.

Students have changed since his college days, Crow says.

"Students seem richer. I never saw a cell phone on campus," he says. "Boys have shorter hair, [and] there are more tattoos."

But the way he feels about being at a college hasn't changed at all. "I have always viewed them as the most exciting places in any town or city," he says.

He still spends hours in the library, although now he can keep it at his fingertips. By strategically placing a couple of wireless laptops around his house, Crow can stop and Google a fact whenever he wants to--something he does about 50 times a day. He frequents the NASA Web site, CNN.com and the Drudge Report, although he doesn't always agree with what it says.

To make sure students can live in the library like he did, the ASU administration recently committed to keeping Hayden Library open 24 hours a day next semester.

To ensure that all students who want to can live in a dorm, he has put dorm construction on the fast track.

In the next couple years, an Academic Village is to be constructed on Apache Boulevard and McAllister Drive, creating 3,000 to 3,500 more beds for any would-be dorm rats. He's also behind an effort to get alcohol off campus.

His administration recently announced that Adelphi Commons, a residence complex slated to house six fraternities, will be alcohol-free.

Crow now lives with his second wife and their 4-year-old daughter in Paradise Valley, in a house that sits between a golf course and a country club. Not that he plays golf. On weekends, he'd rather hike or mountain bike.

He tries to catch a movie from time to time. Recent films he has seen include Fog of War, Girl with a Pearl Earring and Lost in Translation. On TV, he prefers "Law and Order," "CSI" and the surgery channel.

He's still restless, shifting from his role of administrator to that of a biotechnician, a politician, salesman, professor or performer, depending on what the circumstances call for. Just like his unfinished Diet Cokes, he starts things he doesn't finish, and throws out hundreds of ideas, "hoping maybe 40 will stick."

Many speculate that his impatience and ambition will lead him to leave ASU in the next couple of years for something bigger and better. But Crow says, no, he's not going anywhere--that there's enough here to keep him interested and challenged for a long time to come.

"I am always satisfied with what I am doing or I change it," he says, and "I am fully satisfied at ASU."

Reach the reporter at lindsay.butler@asu.edu.