In "Million Dollar Baby," actress Hilary Swank plays a stubborn woman who will stop at nothing to establish herself in the boxing profession.

The movie, and what trainers say is an all-time high enrollment for female competitors, have taught the public two things: one, Hilary Swank can kick ass and two, male-dominated sports like boxing and Ju-jitsu aren't just boys' clubs anymore.

Taking hits

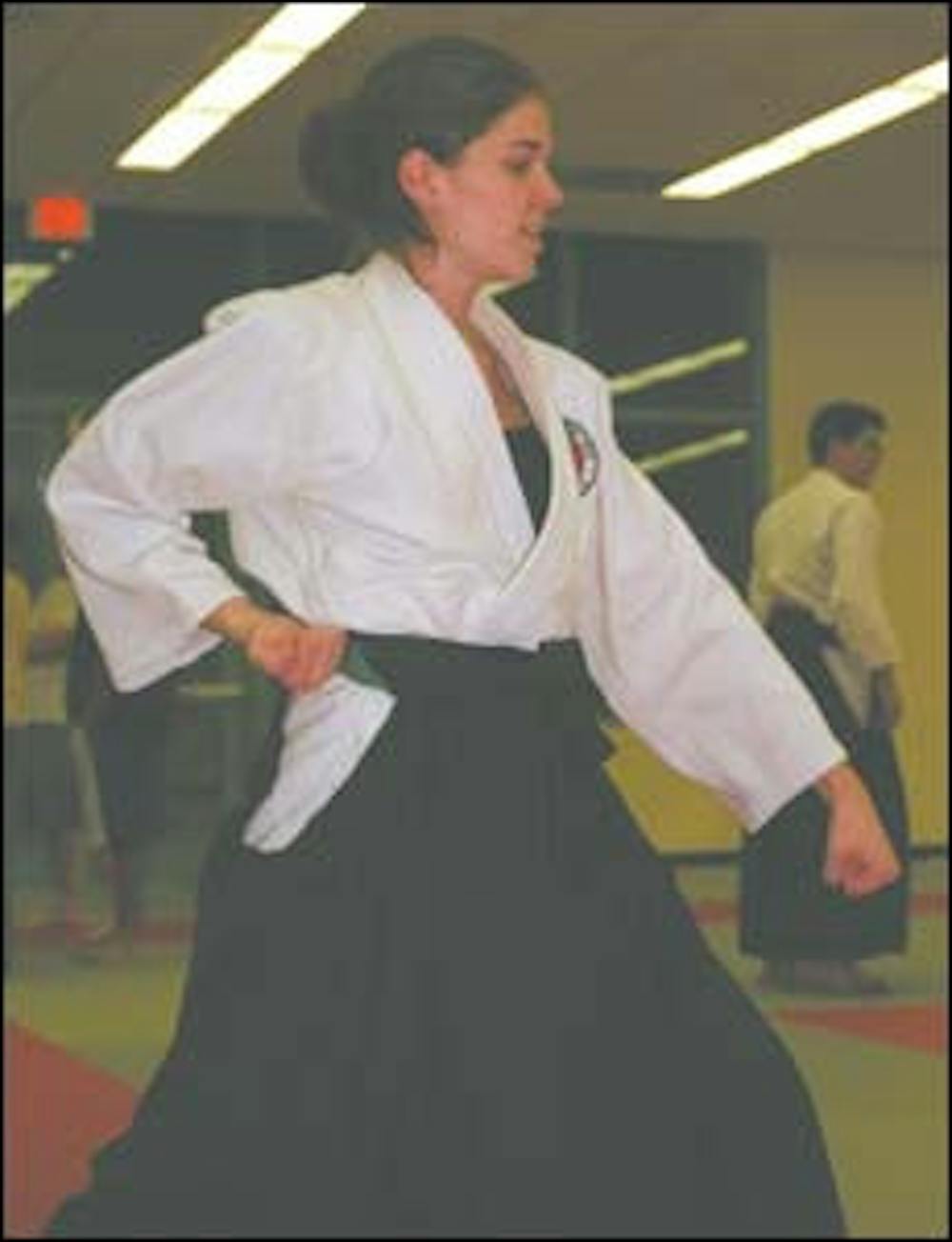

Julie Lorenzen grabs the man standing behind her by his head and throws him over her shoulder.

He thumps onto the mat, the vibrations of the impact reverberating off the floor.

At about 5 feet 6 inches, Lorenzen is smaller than the men in the club, but she throws them effortlessly, as if they weighed nothing.

"A little whiplash never hurt anyone," says the psychology senior.

It's Wednesday night, and Lorenzen is sparring at a practice for the ASU Ju-jitsu Club. There are about 30 other members, ranging from white to black belts.

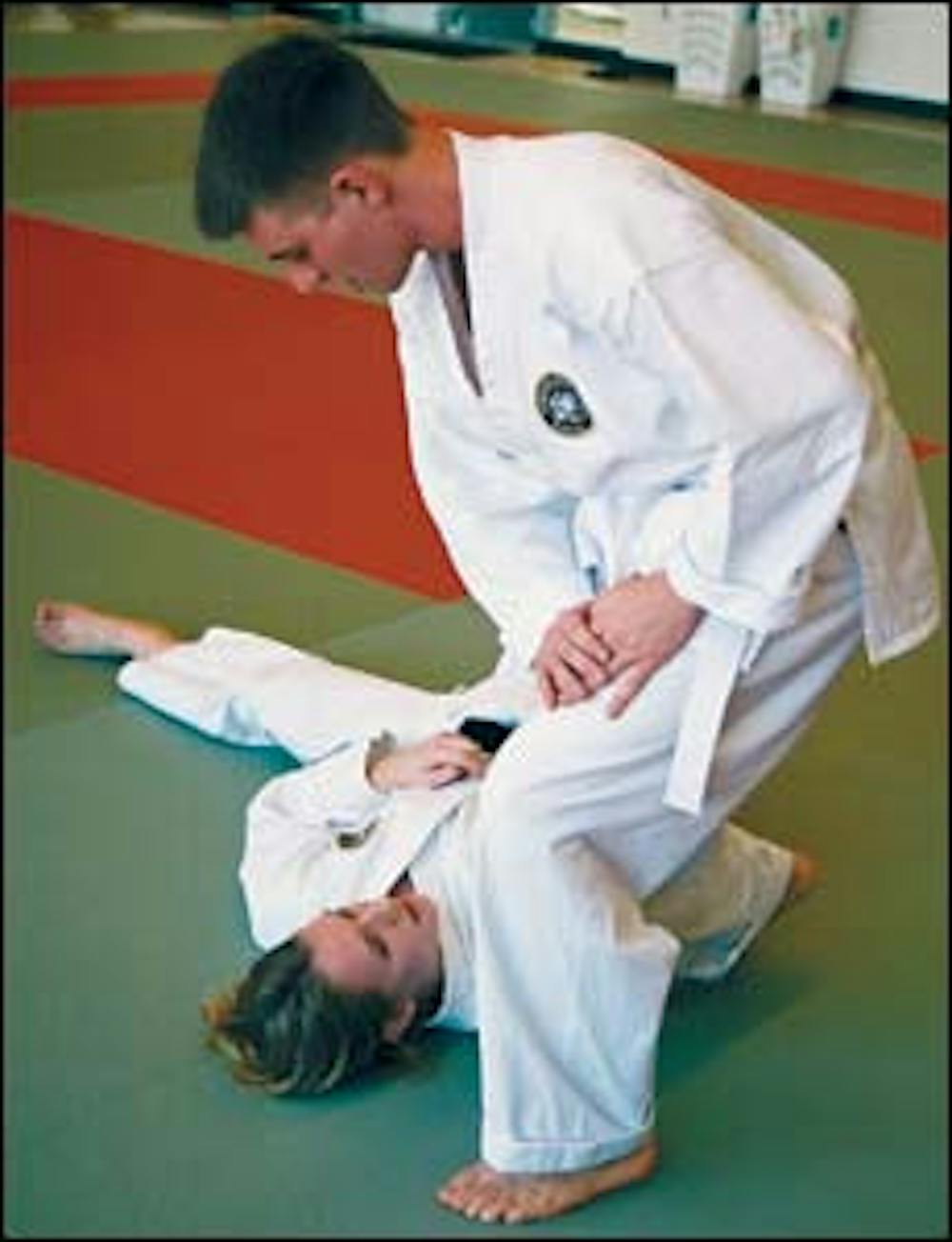

Ju-jitsu, a grappling sport with submission holds including arm bars and chokes, was the primary unarmed fighting skill used by the Japanese Samurai and is considered the mother of all Japanese martial arts. In Ju-jitsu, knowledge of holds is what dictates who wins, no matter how small the competitor.

At the ASU Ju-jitsu Club, the higher-ranked fighters wear long, flowing black hakamas over their traditional Japanese martial arts uniforms, which look like long skirts with high slits cut on the sides. Hakamas represent rank distinction and are only reserved for the most skilled.

Lorenzen is wearing one.

In a room full of men, Lorenzen is one of only three females. Of the three, she is the most skilled and is the president of the club.

Although she trains side-by-side with male students, Lorenzen says gender is not an issue.

"Male-to-female ratio fluctuates, but you wouldn't notice it around here," says Lorenzen, whose short, brown hair is tied back in a ponytail. "It doesn't feel gender-dominated; it feels like a club. Everyone is treated equally."

Lorenzen says she takes her fair share of hits.

"Once you've taken enough falls, they [the men] understand that you're going to walk it off. When you're being thrown on a mat, you're being thrown on a mat. It makes no difference if you're a boy or a girl."

Lorenzen, whose bright eyes glisten like the sweat on her forehead, says when she first started Ju-jitsu in the beginner's class, the male-to-female ratio was almost equal. But as she rose in rank, the presence of women dwindled.

But that didn't disappoint her.

"I have an advantage because my female body is different, in terms of balance. I have a low center of balance, and that's good in any sport that involves judo-style throwing."

David Winters, a Ju-jitsu instructor who trains Lorenzen, says the physiological fact that women have less muscle than men might actually be a blessing in disguise.

"Women really tend to learn the techniques faster because they can't rely on muscle," he says.

Lorenzen says when she began the sport, sparring with men was awkward because so much of Ju-jitsu involves close, physical contact. However, she says she is over that and realizes that the true meaning of the sport surpasses any gender obstacles.

"Ju-jitsu's about becoming a joshu, a helper," she says, "It's not about becoming one of the guys."

However, Lorenzen says she feels a sense of accomplishment for being one of the few women to truly commit to the Ju-jitsu club.

"I've learned that I can take a hit. I can get thrown to the ground, get beaten up a little and I can get through it," she says. "It makes no difference that I'm a girl. I am no less than anybody in the club."

Walking tall

For Japanese sophomore Ellen Kincaid, Kokondo came in lieu of basketball. At 6-feet-tall with blonde hair and a contagious laugh, Kincaid started Kokondo, a hybrid of Karate and Ju-jitsu, when she got bored with conventional high school sports.

"If I had been the only girl on the first day, it would've been weird," she says. "But I went in with a girlfriend and by the time I was really into it, I knew everybody really well."

Unfortunately, many of the girls dropped out and it became lonely on top. For a long time, she was the only girl, which she says was a challenge.

"I feel like I'm more out there because of it. I feel like I have more to prove ... but it's OK with me."

However, Kincaid says she is not OK with being treated differently because of her sex, an experience she says she has encountered throughout the years.

"People won't throw or punch me as hard. It kind of bothers me," Kincaid says.

Aron Cummings, who is president of the ASU Kokondo club, says Kincaid's natural physical talent and tremendous level of dedication contribute to her excellence in the sport.

However, he adds that Kincaid faces more challenges as a woman because of the male ego.

"Men are supposedly physically superior to women, so when a woman competes in a male-dominated sport, many of the male participants see that as a threat to their manhood."

Seth Pate, Kincaid's sparring partner, says at first, he liked that Kincaid smelled better than most of the guys, but that he soon realized those traits don't make a difference.

"I used to offer her my hand to help her up off the floor after I had thrown her, but she laughed at me. So I got over that habit quick," he says. "It's just a matter of learning to think of your partner as a fellow student, not a male or female."

Pate says that unlike some men, he doesn't feel awkward or embarrassed fighting a girl.

"There's always going to be folks that think it's wrong to let a girl into Karate," he says. "But then again, Ellen can probably kick their asses."

Kincaid says Kokondo has definitely contributed to a better way of life for her. She mentally and physically calms herself with Karate techniques and believes the spirituality of it has helped her tremendously. As a result, she says she has learned to trust others more, especially those with whom she spars.

"You really learn to trust the people you're hurting ... and being hurt by."

She says her self-confidence also has improved. She walks differently now, her head a little higher, her shoulders raised, but she doesn't care if that intimidates some men.

"The way I see it," she says, "my height scares guys just as much as my being a black belt."

Pushing herself

Jenah Duea looks like a supermodel.

The management senior from Iowa has long limbs, a killer physique and a touch of naivete; she doesn't understand why her family doesn't support her decision to box.

"My parents didn't think it was a good idea at first. It's a hard sport to understand," she says. "No one gets it until they do it."

As an accomplished high school athlete, Duea played volleyball, basketball, softball and golf. Being physically active was always a part of her life.

During the 2002 winter break, she went looking for self-defense classes. To her surprise, many of the gyms she visited didn't have any. When an employee suggested boxing classes, she decided to give it a try.

"I had tried other things, like yoga, but it was so boring," she says. "And I wanted to do something different than an aerobics class."

Eventually, Duea found the ASU Boxing Club and that's what put her in the competitive field. But she has yet to test her skills."I've tried to get matches, but there aren't any girls in my (145-pound) weight category. There aren't many female boxers in Arizona," she says.

Duea makes up for the lack of matches by additional training at Club SAR, a gym in Scottsdale.

"They [the trainers] didn't know what to do with me," she says. "They had never trained a girl before. But once I got in there and proved I could work just as hard as the guys, they trained me like just like everybody else."

Duea's practices run for 90 minutes a day, five days a week. She also runs in the mornings but does not lift weights. She says that's because it's important to be flexible, and getting bulky could slow down the movements needed for quick jabs. However, Duea says she has gained more muscle because of the physical regimen of the sport.

"I realized how fit I can be and how much I can push myself. It's all about pushing yourself," she says.

She attributes boxing to her rise in self-confidence. Work in the ring has improved her mental focus, and therefore, her work in the classroom.

Boxing also filled her need to learn self-defense.

"Sometimes I'll be walking along and I'm like, 'OK, if someone attacks me, I'm going to do this ... or that,' " she says with a laugh.

But Duea says her major problem isn't fighting off bad guys in the street or other competitors in the ring. She says fighting gender stereotypes that come along with being a female boxer has been her biggest challenge.

Duea says people tell her she should act more like a girl, but she says she'll always be more interested in finding one to fight.

And although she has sparred with guys before, many of them find it difficult to hit a girl. But only at first.

"They get over that," Duea says. "They'll hit me back once I hit them."

On the rise

Joe Leinhauser, owner of Irongloves Boxing Gym and a former amateur boxer, says he's never seen such an increase in female boxers than in the last five years. Of the total number of boxers enrolled at his gym, he says between 40 to 60 percent are female, depending on the season.

Leinhauser attributes the increase to how mainstream boxing has become. More and more celebrities are doing it, HBO now televises female boxing matches and movies like "Girlfight" and "Million Dollar Baby," which was nominated for seven Academy Awards, are showing the public that girls can fight, too.

Leinhauser says his clientele alone proves how mainstream boxing is.

"We get females from all walks of life in here, from 19 to 42. We have college students to housewives," he says. "They're figuring out that boxing gives better results than weight training and it also improves their self esteem and confidence because there's something liberating about punching a bag and releasing all the tension."

As if positive emotional and physical results aren't enough, females might actually be better boxers than males, he says. Women have the innate ability to do what so many guys don't: listen.

"We train the girls just like the guys," he says. "We don't treat them any differently, but I've noticed that they listen more carefully to what the trainers have to say so they catch onto the techniques a lot quicker than the guys."

Leinhauser says the versatility of boxing also attracts women to the sport.

"It's for girls who are already physically active and want a change, and it's tough enough for girls who want to lose weight and get fit."

And it's also for girls like Duea, Kincaid and Lorenzen, who are out there proving that sports like boxing, Kokondo and Ju-jitsu, aren't just for men.

"Most people are actually cool with it, but a small percentage aren't," says Duea. "If it comes out in conversation that I'm a boxer, they're just like, 'You shouldn't be doing that. You're too pretty to be doing that. It'll ruin your face.' "

Reach the reporter at mindy.lee@asu.edu.