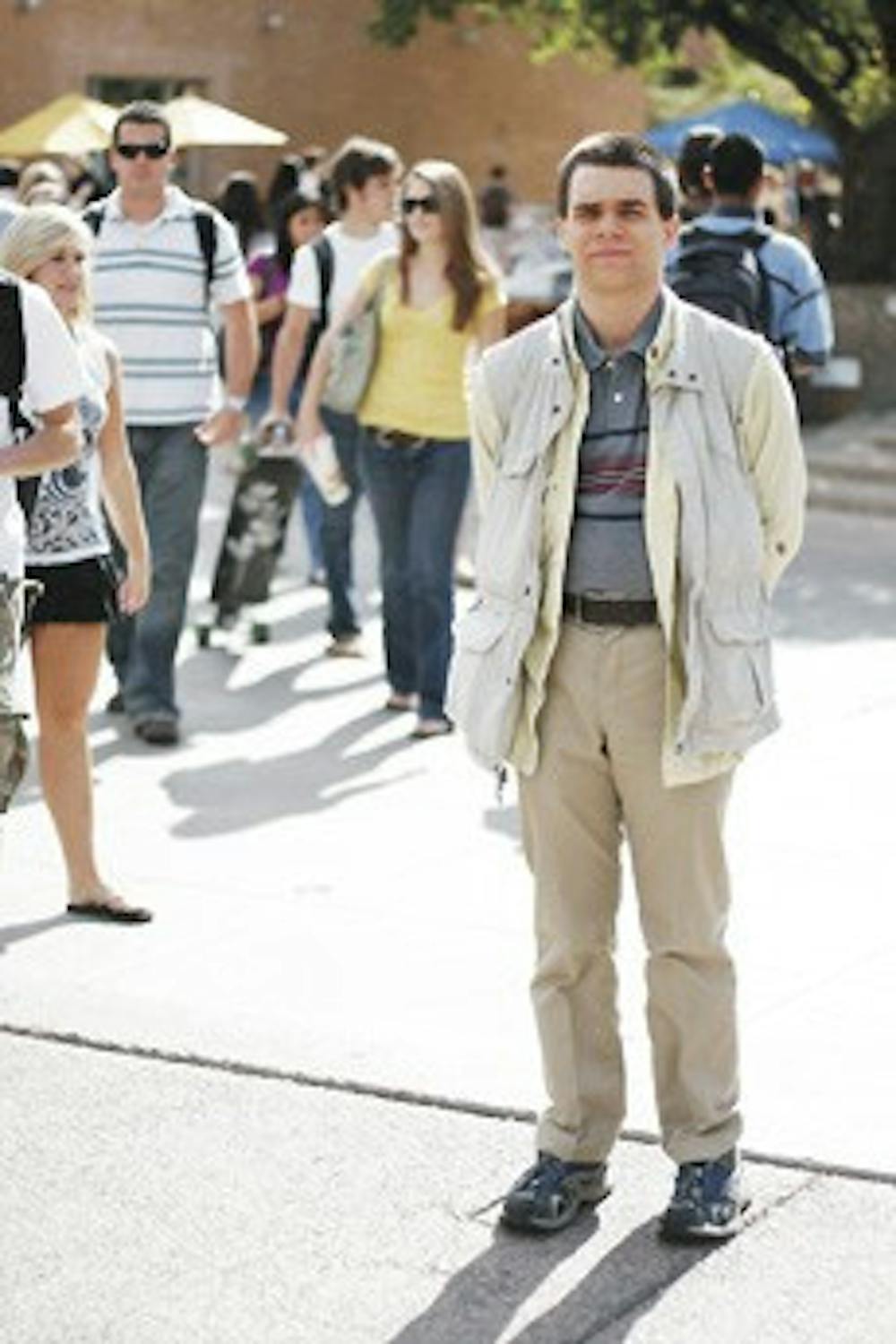

Mechanical engineering senior Matthew's* daily routine is much like any other student's. He gets up, goes to classes, studies in the library and heads home among the sea of other students at ASU.

But Matthew says he often feels very alone. He spends most of his free-time on campus in the Noble Science Library, where it's quiet and social skills are rarely necessary.

"I don't really have a lot of friends," he says.

When he was in middle school, Matthew was diagnosed with a form of autism, a complex neurological disorder that specifically impacts social interaction and communication skills. As a result, though one in every 150 American children is born with autism, most people with the disorder feel profoundly isolated.

People with low-functioning autism are too impaired to live on their own and attend college in adulthood. However, those with high-functioning autism, including some Arizona State University students, often perform well in a university setting.

But even high-functioning autism is considered socially crippling. For ASU students living with autism, attending one of the largest universities in the nation can make each day a difficult feat.

'The obstacles are huge'

When Matthew was diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome, a form of high-functioning autism, he says it came as "a package deal." Matthew has Attention Deficit Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Auditory Processing Disorder, in addition to AS. "The deeper you go into the [autistic] spectrum, the more it becomes a disorder," he says.

Those with high-functioning autism are often characterized by obsessive routines, insistence on sameness and an unusually high interest in a particular subject, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. AS, specifically, is characterized by impairment in language and communication, restrictive patterns of thought or behavior, and repetitive routines, according to the Institute.

Those with the disorder may also have an inability to interact successfully with their peers, problems with non-verbal communication, uncoordinated motor movements and the use of peculiar speech and language, such as speaking in a monotonous tone or taking figures of speech literally.

The obstacles that college students with autism face are huge, engineering professor James Adams says. Adams is the director of the Autism/Asperger's Research Program at ASU and president of the Greater Phoenix Chapter of the Autism Society of America. His 15-year-old daughter was diagnosed with severe autism when she was about 2 years old.

There is no way of gauging how many college students have autism, according to Bridges4Kids, an organization that aims to bridge the gap between schools and communities. The organization says that many students with autism go undiagnosed and are perceived as simply a little strange.

"It's not a question of ability. It's a question of fitting in," Adams says. The research is grim for autistic college graduates, he adds.

"Ninety percent [of autistic college graduates] are unable to hold down a job and live independently, and most have one or less social interaction per month," he says. "I knew a student [with high-functioning autism] who had a 3.5 GPA and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering. After he graduated, he couldn't hold down a job in computer-aided design, and now he's doing janitorial work."

Because of extreme social anxiety and a general inability to interact normally with others, people with autism are usually not prime candidates for job positions that require social skills.

Matthew says it's not easy for him to socialize with people because of the stress it causes him.

"I can't work in the social aspect," Matthew says. He doesn't fully understand the concept of "breaking the ice" when first meeting someone. "What is the ice? How do [people with autism] approach that? It's just not as easy to get my foot in the door. … I am sort of a loner."

A disorder with many misconceptions

Because the general public typically knows so little about autism, people often have many misconceptions about what the disorder truly is, according to the Autism Research Institute.

Those with autism simply learn and develop slower than those without the developmental disorder, Adams says. "An 18-year-old [with low-functioning autism] may be at the developmental level of a 6-year-old," he says.

There are also many assumptions that people with autism are antisocial, don't make eye contact and lack affection, according to the Autism Research Institute. Janet Kirwan, director of family services at Southwest Autism Research and Resource Center in Phoenix, says this is a misconception.

"A lot of people with autism are affectionate, especially with their immediate families," says Kirwin, whose 19-year-old son is autistic. She says that most ideas of autism come from the popular film "Rain Man." The film is based on Kim Peek, an actual autistic man with a photographic memory.

But Peek's autistic symptom is rare. "Fewer than 10 percent of people with autism have [this ability]," Kirwan says.

Unlike the film, those with autism are also not necessarily easily identifiable. The symptoms of high-functioning autism are rarely apparent within the first few years of life, so it is diagnosed much later than most neurological disorders. Most high-functioning autism is detected and diagnosed between 5 years of age and early adolescence, Kirwan says.

The general public cannot recognize people with autism by distinctive facial characteristics, like some disorders such as Down syndrome.

Matthew says he feels like most people aren't aware that there is an autistic spectrum with ranging intensities of symptoms. "You can't even spot us unless you know what to look for," Matthew says. "We come across as eccentric."

To deal with AS and the social anxiety it entails, Matthew says he has worked with Tai Chi, a Chinese form of meditation. Ultimately, he says he came to terms with his capabilities. "You have to accept what you can and can't do," Matthew says. "I can't take on the world."

Matthew says there are a few ways people with autism learn to cope in social settings. These methods include mimicking people without mental disorders and learning how people without autism operate in order to better understand.

Many people with low-functioning autism don't have the ability to master these coping techniques and can't live completely independently or deal with social settings such as a college campus.

Trying to compensate

Another common characteristic of those with high-functioning autism is obsession with one particular subject that may seem irrelevant or bizarre to people without the disorder. Often, they are trying to compensate for a common inability to interpret and make sense of the world around them.

Matthew says that the better a person with autism is able to compensate, the more high-functioning his or her autism is.

Matthew copes by using what he calls his "human behavioral model," which he says he formed based on observing other people and observing himself.

In the model, Matthew lays out what he believes to be the basic operating system for human beings. He says that the model is how he makes sense of the human behavior he observes every day. He refers to people without mental disorders as "neurotypicals," in that their brains function in a way that is typical of the masses.

Pages and pages of tables, diagrams, research, quotations and commentary make up the model, in which he often compares humans to computers. Matthew keeps the model on his computer, where he can add or change information.

"Just like a computer will not operate properly without the proper scripts and drivers, so it is with a human when they're operating in this lower-path processing," Matthew explains in his model. "This is part of the problem with people with Asperger's Syndrome being able to adapt, as they do not possess the built-in scripts and drivers to deal with neurotypicals in the same way neurotypicals can."

Matthew says he thinks the brain is the same among people universally. "There are just different biases in how the [brain] is operated among individuals," Matthew says.

Matthew's observations in his "human behavioral model" help him to cope and understand the way in which "neurotypicals" work and behave.

There was a certain amount of angst involved while forming his 'human behavioral model,' Matthew says. "I didn't want to believe people were so simple that I could construct a model," Matthew says. He says making the model was more out of necessity than fascination.

Often, concentrating on one particular subject is the only way people with autism can concentrate at all.

Going against expectations

But college students living with autism can overcome the obstacles, as Yeou-Luen Ni, a 40-year-old ASU graduate, has proven. Ni was diagnosed with high-functioning autism when he was 5 years old. At 6, Ni began to speak for the first time.

Ni was born in Taiwan, where there is even less research and treatment available for those with autism, says Ni's sister, Yo-Yi. When Ni's family suspected that he might have a mental disorder, they went to a doctor who diagnosed him with autism and told them there was no cure.

"Our extended family members tried to convince us to give him up," Yo-Yi says. "They said there was no future for him, no future for our family."

Yo-Yi says people with autism in Taiwan are often disregarded and institutionalized at an early age. "Our parents sacrificed a lot," Yo-Yi says. "My mother made three times the average salary in Taiwan, and she gave up her career to care for my brother. [Our parents] couldn't find a school that would teach him."

Ni went on to earn a bachelor's degree in mathematics in Taiwan, and moved to America in 1992 when he was 25 years old. In August 2004, Ni graduated with a masters' degree in computer science, after beginning the program in August 1996.

He says he went through language therapy for many years and worked with ASU's Disability Resource Center to get help for the things he needed. "They made accommodations for me," Ni says. "I would sometimes get double the time to complete assignments, especially exams."

Yo-Yi says Ni was the first autistic person from Taiwan to attend a four-year American university and graduate. "It changed the way people [involved in the autistic community in Taiwan] viewed autism," she says. "It meant that their [autistic] kids had a chance, too."

A blessing in disguise

Despite the social inconveniences that autistic people face, there are certain characteristics of the disorder that enable students with autism to go above and beyond non-autistic students.

Adams, with the Autism/Asperger's Research Program at ASU, says that autistic students are generally persistent, loyal and do what is asked of them. "I knew a girl [with high-functioning autism] that was asked to write a three-page paper on a particular subject," he says. "She ended up writing a 20-page paper because she was very interested in the topic being discussed."

Matthew says he feels that people with high-functioning autism are often more logical, perceptive and intelligent in general. "Because you've had to fight, you can work so much harder," he says.

Matthew is planning to graduate in December.

Many families, like Ni's, say they feel that having autistic children creates a close bond between family members because of the intense involvement required in the lives of their autistic children.

Yo-Yi says that having a brother with autism brought her family closer together and reinforced a strong trust among her family members.

"It's unfortunate that [my brother] Yeou-Luen has autism, but in a way, it's a good thing," Yo-Yi says. "The love and caring we experience is so strong and powerful."

*Editor's note: When this article was printed in our weekly publication, Matthew's full name was used. However, because anti-discrimination laws do not cover Asperger's syndrome, Matthew requested only his first name be used, so that he could not be searched online and potentially discriminated against by employers because of his condition. As a result, his name was edited at his request.