When political science junior Jonathan Alanis was hired as a policy intern for a research center at Arizona State University last summer, he never expected that university-wide budget cuts would render him jobless within a few short months.

“I heard that budget cuts were coming,” says Alanis, 21, “but I always felt like [they] would never hit me. I felt like I was off to such a great start with that job…I was part of something, and then all of a sudden it stopped.”

One of three student workers employed by the North American Center for Transborder Studies (NACTS), Alanis abruptly found himself with a difficult choice to make: either keep the internship without pay, or find a new job elsewhere.

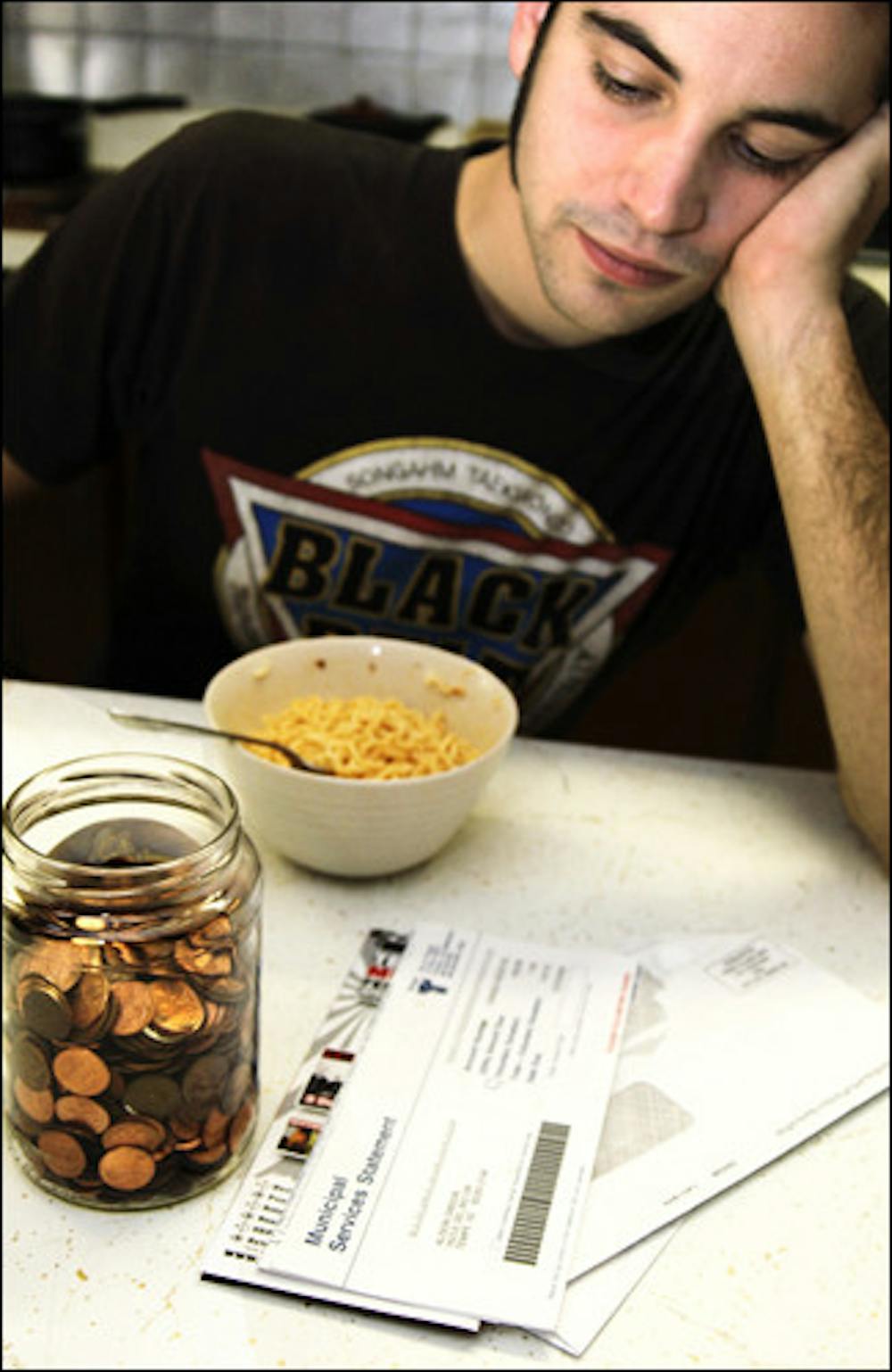

Faced with mounting bills and other living expenses, he chose the latter.

“I couldn’t afford anything…” he says. “I knew I had to leave. I made some calls, called about seven different business owners I knew, different departments at ASU, but no one had anything.”

The timing of the center’s layoffs was particularly unfortunate, as they came barely a week after President Crow distributed a video message to students assuring them that tough economic times would only minimally affect them — if at all.

“You all are […] in one of the safest ports in the storm,” he said in his video, which was sent to students via email. “College students are well supported overall by the infrastructure that we have, […] by Pell grants, by university financial aid … and many of you have that support in addition to strong support from your families.”

While clearly intended to be more of a statement about educational costs than student livelihood, the message nevertheless underplays the negative impacts of budget cuts on students — especially considering that 61 percent of ASU students work at least part-time, with 5,553 of those employed by the university. Then again, much of the information presented by ASU regarding their responses to the recent economic downturn has underplayed its potential (or actual) effects on students.

While the university admits to eliminating 550 staff positions, including deans and department chairs, and warns of potential additional lay-offs to come in 2010 , no concrete information is available regarding budget-related elimination of student positions or reductions in student worker hours or pay (though anecdotal evidence may abound).

While most students probably won’t experience the impact of budget cuts as profoundly as Alanis has, they are nevertheless feeling them in different ways — as can be surmised by the1,000 student strong protest of proposed budget cuts that took place last January at the State Capitol.

Lindsay Cashen, a freshman at ASU, is one of many new students who are increasingly worried about the budget cuts and the impact they will have on her life. In particular, she’s concerned about the impending tuition increases and her family’s inability to help cover her educational costs.

“I have a small scholarship,” she says, “but it doesn’t go up with the rising cost of tuition.”

The increasing cost of attendance has become an ever more prevalent concern for students in the last several months, as per student state funding has decreased from $7,976 to $6,400 — which is only $4 greater than per student state funding a decade ago. According to a statement issued by President Cross last January, “This amounts to having more than 30,000 of our 67,000 students with no state investment whatsoever.”

Additionally, the university has suspended AIMS scholarships.

Rising attendance costs, paired with decreased funding sources, has many students concerned. Cashen plans to take out a private loan that will help her pay for school, but worries that banks’ reactions to the economic crisis will inhibit her from doing so. “If I don’t get approved, I won’t be able to continue at ASU,” she says, “It’s really challenging and frustrating.”

Alanis expresses similar feelings of frustration about his own situation. While he’s grateful to be employed again, he says he still feels the pinch of tough economic times. A two-dollar pay difference is a lot when you’re living paycheck-to-paycheck, he stresses — not to mention the daily cost of his new 30-40 minute commute.

While he and Cashen, admittedly, receive support from their families, President Crow might be disappointed to hear that this family support is not so strong nor as certain as his video message implies.

“My family struggles to help me with my household expenses,” he says, adding that his precarious financial situation has drastically changed his and his family’s plans for the future. “I am under a lot of stress…I probably won’t be able to go to grad school right away now, because I’ll have to enter the workforce right away to start making some money…My parents told me they couldn’t afford me anymore.”

His situation has presented other challenges, as well. The stress of being laid off from a professionally rewarding position played out in his new job, for which he felt overqualified. “I didn’t feel motivated,” he says. “I was used to being part of something, and now I’m serving coffee. I got kind of depressed.”

Alanis and Cashen are not alone. Most of the country appears to be worried about the financial situation, with stress levels increasing accordingly. It’s such an issue, in fact, that Counseling & Consultation (C&C) services at ASU has added resources to their website specifically for students who experience difficulties coping with tough economic times.

While the C&C does not report a surge in new cases, they are noticing that their current clients are talking more and more about financial issues.

“The reality is that students are talking about these stressors,” says Martha Christiansen, the director of C&C, “Money and work are already the two top sources of stress for about 75 percent of people in the United States…Stress during these difficult times may be more constant than that associated with the academic calendar and achievement of academic goals. We like to be proactive. We’re the only [university] that has material reaching out to students in this way.”

In addition to financial and emotional effects of budget cuts and the economic downturn, students are also — understandably — concerned about how these issues will affect the quality of their educations.

ASU has already closed nearly 50 academic programs, disestablished the School of Applied Art and Sciences, and officials say that cuts possible in 2010 could result in the closure of the Polytechnic and West Campuses.

In a state already infamous for its poor educational system, such drastic cuts have had, and will continue to have, profound effects on the quality of education of in Arizona.

A recent report from the W. P. Carey School of Business’s Office of the University Economist affirms this, stating that not only does “the higher education system in Arizona receives resources far below the national average,” but that the level of these appropriations has not been adequate enough to satisfy the state of Arizona’s constitutional requirement for education funding.

This is occurring “despite increasing evidence that investments in higher education yield quantifiable societal returns in addition to the widely recognized private financial returns,” the report reads.

While the university is obviously not itself responsible for the statewide cuts to education spending, having repeatedly and publicly decried them, the reality of decreased education funding and the university’s apparent lack of attention to its widespread and multifaceted impacts on individual students and their wellbeing begs the question: What is the New American University becoming?

For more information about how to deal with stress related to money and the economy, visit: http://students.asu.edu/counseling

Reach the reporter at Catherine.Traywick@asu.edu.