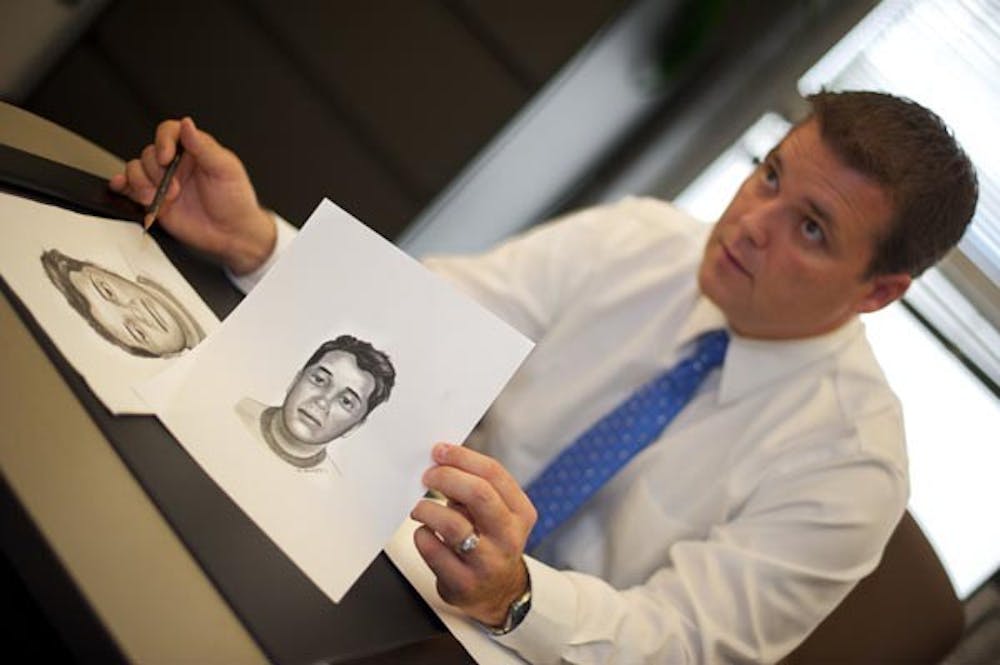

Some may not call law enforcement an art, but don’t tell that to ASU Police Cmdr. Mike Thompson.

Aside from his duties as the administrative commander of the ASU Police Department, Thompson is the department’s lone composite sketch artist, and his talent is in demand.

The FBI and several other agencies in the Valley have taken advantage of Thompson’s skill, contracting him to draw composite sketches of kidnapping and robbery suspects, and even cases in his own ASU backyard.

Last year, a recent graduate was leaving a get-together with friends when two men forced him into his car at knifepoint and made him drive, Thompson said.

When the student stopped the car to get gas, he fled and the two suspects drove away, Thompson said.

The student got a good look at the face of one of the suspects, and Thompson said he drew a composite sketch of the man to aid in the investigation.

The case is still open, Thompson said, but ASU Police are fairly sure they’ve identified the suspects and are now working to finalize the case.

Before coming to the ASU Police Department in 2008, Thompson started as a civil engineer for the city of Mesa. He then joined the Mesa Police Department in 1988, where he worked for 20 years, starting as a patrol officer and working his way up to detective by 1994.

ASU Police Cmdr. Jim Hardina said Thompson also benefits the department because contracting composite sketches can be expensive. Thompson, he said, alleviates these costs.

Political science and global studies senior Dominick Howard said it’s good to know there’s a sketch artist working with campus police.

“ASU Police are watching over 60,000 people,” Howard said. “It’s good they have a sketch artist because it can be an integral part in finding suspects and closing cases.”

When Thompson became a detective, he said he began to see his window of opportunity to start doing composite sketches.

“We had a guy in the department that was doing composites, but I thought the quality could have been a lot better,” Thompson said. “Other detectives wondered why all of his composites looked the same. One day I caught my boss in a good mood and showed him my drawings, and he said they could always use one more composite artist.”

From there, Thompson attended a weeklong police composite art class at Scottsdale Artists’ School.

That class covered all the basics on suspect drawing, but Thompson said he stayed another week at the school to take a class on reconstruction in case police discovered the skull of an unknown person. He could then work with an anthropologist to make sketches of that person.

In 1998, Thompson was invited to the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va., to participate in a month-long forensic art school. The class covered not only drawing composite sketches, but also how to create two- and three-dimensional reconstructions of a person.

After the completion of the course at the FBI Academy, Thompson said he was contracted by the FBI to do composites several times.

One case in which the FBI was very thankful for Thompson’s work, he said, was when keys belonging to a member of the FBI SWAT team were stolen, and the agent’s weapons and wallet were taken from his vehicle.

The suspect purchased three laptops from a Best Buy using the agent’s credit card, and a composite based on the description of the man from a cashier at the store led to the man’s capture and recovery of all of the agent’s weapons.

The art of composite sketches, however, isn’t always perfect.

“It would be fantastic if we could draw an exact portrait of someone and say ‘that is the guy,’ but you're talking about someone who only saw a person for a few seconds, and there's trauma involved,” Thompson said.

After completing a drawing, he said he asks the witness to rate it on a scale of one through 10 based on how much the drawing looks like the person. He said he has seen an average score of seven or eight.

Still, Thompson said, some drawings become very difficult based on witness statements.

“There are times where [witnesses] say ‘his eyes were bigger than that, bigger than that, bigger than that,’ and I’m thinking this guy should be from Area 51,” Thompson said. “I have to draw what they tell me. I wasn’t there; I have to report exactly what they tell me.”

However, Thompson won’t do a drawing if there aren’t good facts from the witness, because “a bad drawing can be more detrimental than no drawing at all.”

Even though unknown suspects in many cases may be identified by video surveillance or fingerprints, Thompson said he still does composites when he can “to make sure all the bases are covered” in an investigation.

“It’s not magic,” Thompson said. “It’s certainly a neat skill to have, and not every agency across the United States has a composite artist.”

Reach the reporter at mhendley@asu.edu