Pitchforks: 3/5

(Photo by Murphy Bannerman)

(Photo by Murphy Bannerman)

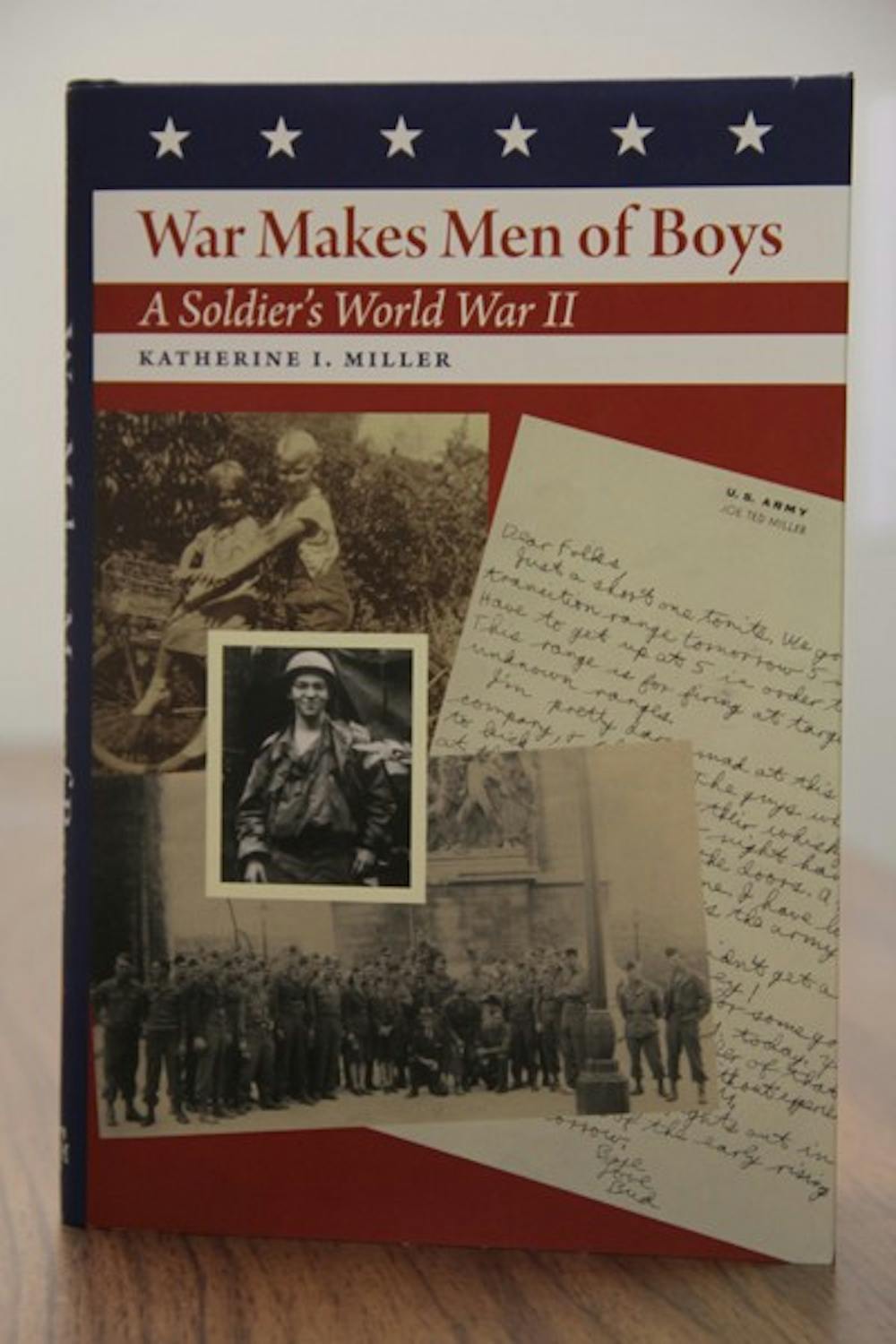

After the death of Katherine Miller’s father, Joe Ted “Bud” Miller, she stumbled across a plethora of wartime letters written by her father to his family. After consulting with her mother and sister, she decided to write a book chronicling the life of her father as he served as a soldier in World War II. This compilation of letters — supplemented with memoirs, research and interviews — eventually would become Miller’s nonfiction war book, “War Makes Men of Boys.”

The book can be easily separated into two parts: the story of Bud’s life in the army and the analysis of how the war changed the boys that were drafted, particularly Miller’s father.

The first half of the book is devoted to telling the story of Bud’s life. The reader is treated to descriptions of childhood memories, before being told about his time in the army. Miller then begins the main tale, so to speak, describing the draft of which Bud was a part, to when he was at basic training, to the time spent in Europe, both during and after the war.

What is important to note about this book is that this is not a typical “war book.” The reader does not “see” or “experience” the war through a first-person account that was recorded in letters or journals. Rarely does the reader see passages from the letters. Rather, Miller only pulls quotes from her father’s letters and analyzes them, giving the reader some insight into what he must have been feeling at the time.

The absence of a first-person account sometimes has a negative impact on the story. For instance, Miller presents a quote near the end of the book about a heart-wrenching scenario — that occurred during Bud’s training — analyzes it and moves on without informing the reader how the situation occurred or what happened to the other people involved. Simply quoting the letters and not presenting them in full can occasionally leave the reader with more questions than a detailed analysis can provide.

While this stylistic choice may discourage some readers from pursing this book, Bud’s time in the army is fascinating and well-worth reading about — even though Miller uses the first person while she analyzes the letters.

The second half of the book expounds upon Bud’s story presented in the beginning. Miller methodically examines the different stages of her father’s life and how the war, along with other significant life events, changed him. She uses multiple scholarly sources and interviews to verify what she finds in Bud’s letters and journals. The understanding and awareness her analysis provides allows the reader to have a new appreciation of what it meant to be a soldier in World War II.

Fans of “action-packed” war books may want to pass on this, as this book is not about war, but about the life of one boy drafted into World War II. The lack of a broader perspective on the war, given through the eyes of multiple soldiers consistently throughout the book, creates a narrow focus on Bud. This does not, necessarily, have a negative impact on the book; it does, however, create a limited audience. On the other hand, the obvious love and care Miller put into creating this book balances out many of the negatives.

If you are a fan of history or psychology and stumble across this book, skip the SparkNotes and actually give it a read — you may be surprised about how much you will enjoy the book.

Reach the reporter at kcbennet@asu.edu.