Down the Navajo Reservation Trail and off to the side of Main Street lie ancient dinosaur tracks giving the local natives a financial opportunity. Once pulled over, a family offers to guide tourists through the tracks working for tips. All the while an American flag waves silently in the backdrop as a testament of perseverance.

Down the Navajo Reservation Trail and off to the side of Main Street lie ancient dinosaur tracks giving the local natives a financial opportunity. Once pulled over, a family offers to guide tourists through the tracks working for tips. All the while an American flag waves silently in the backdrop as a testament of perseverance.Photo by Mackenzie McCreary

It’s quiet.

There are no honking car horns, loud cell-phone conversations or static city noises that seem to come from everywhere and nowhere at once.

On the outskirts of the Navajo reservation in Tuba City, Ariz., the rocky, red terrain of the desert bakes under the harsh sun and endless blue sky freckled with white clouds. A conspicuous red and yellow billboard advertises a McDonald’s — it is the only remnant of civilization to be seen for miles. A car with a muttering motor passes on the road into the heart of the reservation. A light breeze skids across the landscape and ruffles the American flag planted near a roadside attraction advertising tours of dinosaur tracks.

Here, life is slow and steady. One would never suspect this serene landscape to serve as the backdrop to a community struggling to fight the odds presented by stereotypes and a traditional community.

The Navajo Nation is the largest Indian reservation in the United States. It covers about 25,000 square miles across Utah, New Mexico and Arizona. According to the Indian Health Service’s (IHS) website, anthropologists believe the Navajos arrived in the Southwest 800 to 1,000 years ago.

The reservation system in the United States really began with the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Americans’ insatiable thirst for land and westward expansion led former President Andrew Jackson to systematically remove Indian tribes from land east of the Mississippi River. In an essay titled, “American Indian Reservations: The First Underclass Areas?” Gary D. Sandefur, a professor of social work and sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said the expulsion of Native Americans continued across the country.

“The lands reserved for Indian use were generally regarded as the least desirable by whites,” Sandefur writes. “For most of the 19th century the policy of the U.S. government was to isolate and concentrate Indians in places with few natural resources, far from contact with developing U.S. economy and society.”

In 1851, the Appropriation Bill for Indian Affairs authorized funds for the movement of western tribes onto reservations as a way to “protect” Native Americans from westward expansion, according to newworldencyclopedia.org.

However, while Native American nations now had their own land, they were still commanded to conform to an impossible ideal of American culture.

The vast red desert spreads in every cardinal direction in Tuba City. And there are testaments of the Navajo culture everywhere one looks, too.

The vast red desert spreads in every cardinal direction in Tuba City. And there are testaments of the Navajo culture everywhere one looks, too.Photo by Mackenzie McCreary

The film, “The Long Walk: Tears of the Navajo,” produced by John Howe of the PBS station KUED in Utah, details the political and cultural torture the Navajo faced throughout their long history.

This cultural persecution was predominantly seen in the early days of the boarding schools set up for Native American children. According to the film, many vital aspects of the Navajo culture, such as language, clothing and hairstyle, were forbidden in the school.

Even the children’s names were changed to drive home the goal of complete Anglo-assimilation.

And while such discrimination against Native Americans is no longer under the limelight, stereotypes are still fueling the divide and as the problems increase, the progress of change remains at a standstill.

Many Native American students report hearing the stereotypical denouncement that the people living on reservations are all alcoholics and drunks. While students working toward a better future for the reservation are angered by this generalization, the Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation reports that 90 percent of the Navajo Nation Police criminal caseload is alcohol related.

Alcohol dependence and abuse can also contribute to the high levels of diabetes reported on reservations across the country.

According to the Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation, alcohol can affect a person’s body in a number of ways. It can stimulate a person’s appetite, which can lead to negative effects on blood sugar control. Alcohol can also increase triglyceride levels, blood pressure and can interfere with the positive effects of diabetes medicines, such as insulin. Coupled with these effects, diabetes has proven itself to be a deadly aspect of Native American living.

The Navajo County Public Health Services released its 2012 Health Status Assessment containing demographic, socioeconomic and other statistics about the Navajo population. While alcohol abuse and diabetes pose two of the largest problems to the Native American population as a whole, there are a myriad of other challenges to be faced.

It's a stereotype yet to be broke and an ongoing health issue: alcoholism.

It's a stereotype yet to be broke and an ongoing health issue: alcoholism.Photo by Mackenzie McCreary

According to the Health Status Assessment, the unemployment rate on Arizona Native American Reservations was two times as high as that of Navajo county, which had a 15 percent unemployment rate. In 2011, 33 percent of Navajo County was living below the poverty line.

Education has also proven itself to be a tough road for the Native American population.

Secondary education is more of a home-driven goal. Many Native American students at ASU say they are mainly encouraged by their parents and other family members to pursue college degrees.

According to a 2011 survey conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics, “Almost two-thirds of AI/AN eighth-graders report never talking to a school counselor about classes for high school or future plans.” The survey reported the students tended to talk about such things with family members and peers.

Many Native American students at ASU report instances of stereotyping because of the ethnicity’s minority status. They say they struggled to adjust to an outside culture that held very different values and modes of respect.

The report lists liberal arts and sciences, nursing and health, engineering, and public programs as the top-four degree programs Native American students pursue at ASU.

Maybe it has something to do with the desire to go back and help.

Four hours and 38 minutes —246 miles — separate the Navajo reservation from ASU’s Tempe campus. But the longing to return home and improve the community is deep-seeded and strong.

It is a tight-knit society built on a history of traditional culture and enduring perseverance. But, the students say it is desperately in need of change through the ideas of the younger generation.

These are the stories of four determined, Native American students from the Navajo reservation, who have battled cultural differences in pursuit of change for their homeland.

Derrick Manson

Kinesiology and pre-med senior Derrick Manson is eager to answer questions about his home.

“I don’t mind explaining things,” he says. “Not many people know about Native Americans so I’m never offended when someone asks a curious question.”

Although his roots are from a very rural, ceremonial-based place called White Valley, Manson lived on the Navajo reservation in Tuba City his entire life before coming to ASU.

“I loved it,” Manson says with a smile, remembering his family’s first house on the reservation. It was a one-acre lot that they shared with another family. He remembers kids running around and playing with each other, and says that everyone knew which kid belonged to which parent.

Manson says that it is the kind of community were everyone knows each other, and he felt there was never anything very bad happening.

“It was nice, it was safe.”

Manson says that the strength of the community translates to a very open and accepting society.

“We’re the majority on the reservation so everyone’s comfortable with each other and even if a minority comes in, we consider them family,” he says. Manson goes on to describe his childhood best friend, who was half-white and half-Navajo. “The community is very welcoming, it doesn’t shun anyone.”

His mother was his biggest influence.

Manson grew up playing with the handicapped and disabled kids his age at the group home where his mother worked as a caretaker.

“My mom has been a caretaker for people as long as I can remember,” he says. “I just got that warm feeling of how she cared for them and grew to really like the medical field.”

Manson says that one of the biggest issues on the reservation is diabetes and the absence of a healthy lifestyle.

“Personally what I would like to see change in the community itself is the awareness of health,” he says. “That’s another reason I want to go into the medical field, I want to educate and influence people to be healthy.”

In 2009, the American Diabetes Association conducted a study entitled “Diabetes in Navajo Youth, Prevalence, Incidence and Clinical Characteristics: The Search for Diabetes in Youth Study.”

The study reports that although adult Pima Indians have the “highest occurrence of type two diabetes in the world,” diabetes in Navajo people has been suggested to be 2-4 times higher than that of non-Hispanic white populations in the same area. The study also states that these levels have been rising over the past 20 to 30 years.

Manson concedes that, along with diabetes, there are many stereotypes about his community.

“A lot of people think we’re disconnected from the outside world, they think that we don’t listen to the same music or see the same things,” he says with a chuckle. “It’s exactly the same, we have satellite television, Internet and everything’s exactly the same.”

Although Manson says his experience living on the reservation was extremely positive, he says he wishes the image of his home could be cast in a more positive light.

“Everyone stereotypes and it’s up to you to find the details about it,” he says. “It’s hard to say what you want to see from people on the outside to perceive about you.”

Manson says that experience is the only way to break this barrier.

“It would be nice for [people] to understand it more but it’s something you really have to experience for yourself,” he explains. “It’s not just black and white, there’s a lot of gray areas. You literally have to go there for more than three months to understand what we’re talking about.”

Anisia Sieweyumptewa

Social work senior Anisia Sieweyumptewa has a soft voice that turns up at the ends of her sentences.

Her dark, highlighted brown hair is tied up in a bun behind her round, smiling face. She wears a purple shirt proudly proclaiming her sisterhood in ASU’s Greek life. Her eyes light up when she describes the homes she has had in rural Arizona.

“It’s a place you can really call home,” Sieweyumptewa says. “You can describe the scenery but it’s a feeling that you can’t really put into words because it’s just so surreal.”

Sieweyumptewa comes from three different tribes: Navajo, Hopi and Chiricahua Apache. Her Chiricahua Apache side comes from her grandfather, Navajo from her mother and Hopi from her father.

“My dad’s side of the family didn’t really accept my mom and that’s the reason why they separated,” she says. “They always treated my mom differently and that’s how it is now. My dad’s side of the family always treats me and my sister in a different way just because we’re half-Navajo.”

But there were other problems lurking within the family.

“My dad was a drinker, so my family struggles with alcohol and its presence in the household,” Sieweyumptewa says. Her voice falters slightly as she says, “I lost a cousin because of alcohol a year ago. It was a little bit harder to keep that in.”

The Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation publishes a monthly newsletter, “Healthy Directions.” In its April 2010 issue the newsletter featured an article on National Alcohol Awareness Month.

“It is a very sobering statistic that 26.5 percent of deaths among Native American men and 13.2 percent of deaths among Native American women are alcohol related,” the article reports.

But while 80 percent of former-drinkers on the Navajo reservation have stopped drinking, smuggling and alcohol dependence lives on in the community.

“Bootlegging alcohol onto the reservation and into the Tuba City area from the Highway 89 corridor is the number one problem,” the article says, as alcohol is not allowed on most reservations in the United States.

Sieweyumpteway says that although alcohol is a serious problem on the reservation, it is also a gross stereotype.

“Indians are always with that stereotype, like they’re always just drunk on the reservation, it’s hard to break that stereotype when it is always present,” she says.

These stereotypes can often lead to a type of underdog feeling — a feeling that the odds are against you. Sieweyumptewa says that getting reservation kids to think about higher education is an issue that is very important to her.

When Sieweyumptewa was old enough to go to kindergarten, her mother moved the family to Tuba City so that the girls could attend the same boarding school their mother had. Sieweyumptewa says her mother has been deeply invested in her education, always highlighting ASU as her school of choice for her children.

“I guess you could say that my mom picked my school for me,” she says. “And I’m fine with that because my mom has always been my number one supporter in education.”

Sieweyumptewa cites programs like the American Indian Resource Program, which educate reservation kids on the transition to college life. This includes workshops for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and exposure to life on a college campus.

“When we have programs like that for our younger generation, it kind of helps them to where they can see the potential in themselves,” Sieweyumptewa says. “It’s a lot more challenging when you know that society looks at you a different way. I think that’s the biggest challenge that our young people have to overcome.”

At first, Sieweyumptewa says she wasn’t sure which major to pursue.

“I just wanted to do something where I could go back home and help my people,” she says. “We see problems on the reservation and no one is trying to advocate to change or make a difference.”

Sieweyumptewa says the deep respect Native Americans have for their elders has led to an avoidance of change. She says that no one tries to question the decisions of an elder leader. But with the world changing at such a rapid pace, maintaining this type of leadership system is almost taboo.

“Things can change for the better,” she says. “But at the same time it takes a very courageous person to make a sudden change.” Sieweyumptewa says that the potential outcomes of changes within the reservation community can be worth the fear.

“It will probably take a lifetime of somebody to go forth with what they want to do. It’s going to be a long journey but, hopefully, I’ll get there,” she says, with a hopeful giggle.

After changing her major three times, Sieweyumptewa found social work and a cause to work for in domestic violence. She’s also discovered an accepting family in Theta Nu Xi Multicultural Sorority Inc. Because of her Navajo-Hopi background and her experience with her parents, Sieweyumptewa was glad to join the accepting community of Theta Nu Xi.

“All my sorority sisters are from different types of backgrounds, but we all have similar interests in breaking stereotypes,” she explains. “I found voice-empowerment and more understanding of other people’s cultures. They didn’t have the same types of issues but it all had the same meaning for us that we got out of it.”

While Sieweyumptewa found a community that accepted her for her heritage, she says she still experienced a type of culture shock when coming to ASU.

“I see it as two totally different worlds,” she says of the reservation and ASU. “They merge but I think they’re always going to be different because of the way the community is structured and the way the people within it are.”

“We don’t get the same treatment as the outside world because we’re Native,” she says.

Sieweyumptewa says that the sense of community and togetherness is so strong on the reservation, but at ASU, the lifestyle is very individualistic.

“When I come here it’s like I have to be successful, I have to be the number one person,” she explains. “But on the reservation, I feel like I have to better myself for these people.”

“On the outside people will ask me why I’m doing that,” Sieweyumptewa adds. “People don’t really understand the connection with going back to help.”

The idea of segregation is apparent in Native American history, and Sieweyumptewa says that this separation further entrenches stereotypes in the social mindset.

Sieweyumptewa says that the younger generation of Native Americans is trying to break the idea of segregation between reservations and the rest of the nation.

“There’s room for improvement and there’s room for growth going in a positive direction,” she says.

“It’s really hard to find someone who wants to sit down and talk with you and really understand what’s going on,” she says. “I feel like if we had more people like that in the world then these stereotypes would falter and we would find solutions by coming together.”

Corey Hemstreet

Justice studies senior Corey Hemstreet has a strong voice filled with passion as she talks about the present problems on the reservation.

“I think as a child you don’t really see the hardships as much as people who are older and understand things,” she says.

Hemstreet says that alcohol was a big part of the problems she and her family faced living on the reservation.

“All you have to do is drive 30 minutes away and there’s an alcohol store right there, so it’s easy access to alcohol,” she says. “Even if they made alcohol illegal, it’s still going to be there.”

These realities only help to perpetuate the stereotype of drunken Native Americans on the reservation. Hemstreet says, “it’s just a few bad apples that make it harder for everyone.”

Hemstreet tells the story of when she experienced how widespread and accepted this stereotype has become outside of the reservation. She talks about how she had been on the lightrail and a drunken man came up to her and started speaking to her in Navajo. Hemstreet got away from him because she was worried about her safety in his presence. However, when she was talking about this incident at work, her coworker said, “Aren’t all Native Americans drunks?”

“At first I got offended and you don’t want to throw back a racial slur because that’s not me,” Hemstreet says. “So I asked her, “Do you think I’m intoxicated right now?”

Her coworker said no. She said: “Native Americans aren’t all drunks.”

Along with this shock of outright stereotyping, came a cultural shock in the form of the education system.

“I noticed that when the teachers were trying to settle down the class, they [the class] were just so rude, and I had never experienced this,” Hemstreet says.

Hemstreet also says that the variety of different people was also a surprise to her.

“Typically on the reservation, Native Americans are the majority so if there was a black or white student, they would be the minority,” she says. “But when I came to ASU, there are just all different kinds of people, different races, nationalities, religions, sexualities, sexual orientation.”

Hemstreet says that it was heartwarming to her to see that there were so many kids that were so different from each other, and the differences don’t really conflict.

“In grade school you might have been teased about your sexual orientation, but here everybody kind of supports it and that’s great,” she says.

Hemstreet is passionate about her big dreams of fighting for people in need.

“I always wanted to be a lawyer, even when I was a little kid,” she says. “I want to work for people who are very vulnerable like women, children, people of color.”

Hemstreet also desires to defy expectations that are traditional to the Navajo Nation — one in particular, is politics.

“This is a big dream of mine,” she says. “I want to be the Navajo Nations President.”

Hemstreet says that, in the Navajo tradition, women are not meant to be leaders. Many say this was apparent in the last Navajo Nation presidential election in 2010. Former Navajo Nation Vice President Ben Shelley campaigned against New Mexico Senator Lynda Lovejoy. Hemstreet’s friend and fellow student Dakota Yazzie, says she went to see the two participate in a debate at ASU during their campaign period.

“In Navajo tradition, a woman is not supposed to be a leader or all these supernatural things will happen,” Yazzie says. “I felt that she was more qualified for the job because she was representing change and moving forward.”

If elected, Lovejoy would have been the first female president in the history of the Navajo Nation. Yazzie says she thinks the Navajo people just said, “No, she’s a woman, she can’t be an elected official,” and thus, Shelley became president.

Hemstreet hopes that both her major and her minor in women and gender studies, will help her accomplish her goal of presidency so that she may enact change in the reservation’s society. Like Sieweyumptewa, she wants to give back.

“You go out and come back, that’s what people expect you to do on the reservation,” she says.

Hemstreet says that there are a lot of problems that don’t get as much attention as they should. One of the main ones is the appearance and safety of the neighborhoods within the reservation.

“I would like to see a lot more recycling and a cleaner community,” Hemstreet says. “It’s always just beer bottles or anything laying around and that place could look so much nicer and prettier if there was no trash or if people actually valued their house and took care of it."

Hemstreet also says that she wishes roads could be fixed, but that it seems both the federal and Navajo governments leave it to each other.

“There are potholes everywhere, the road itself is a liability,” she says. “It is hazardous, especially for ambulances that are trying to get to people in need.”

In order for change to happen, Hemstreet agrees with Manson that people and federal government officials need to visit the reservation for a significant amount of time to really understand the things that need to be changed.

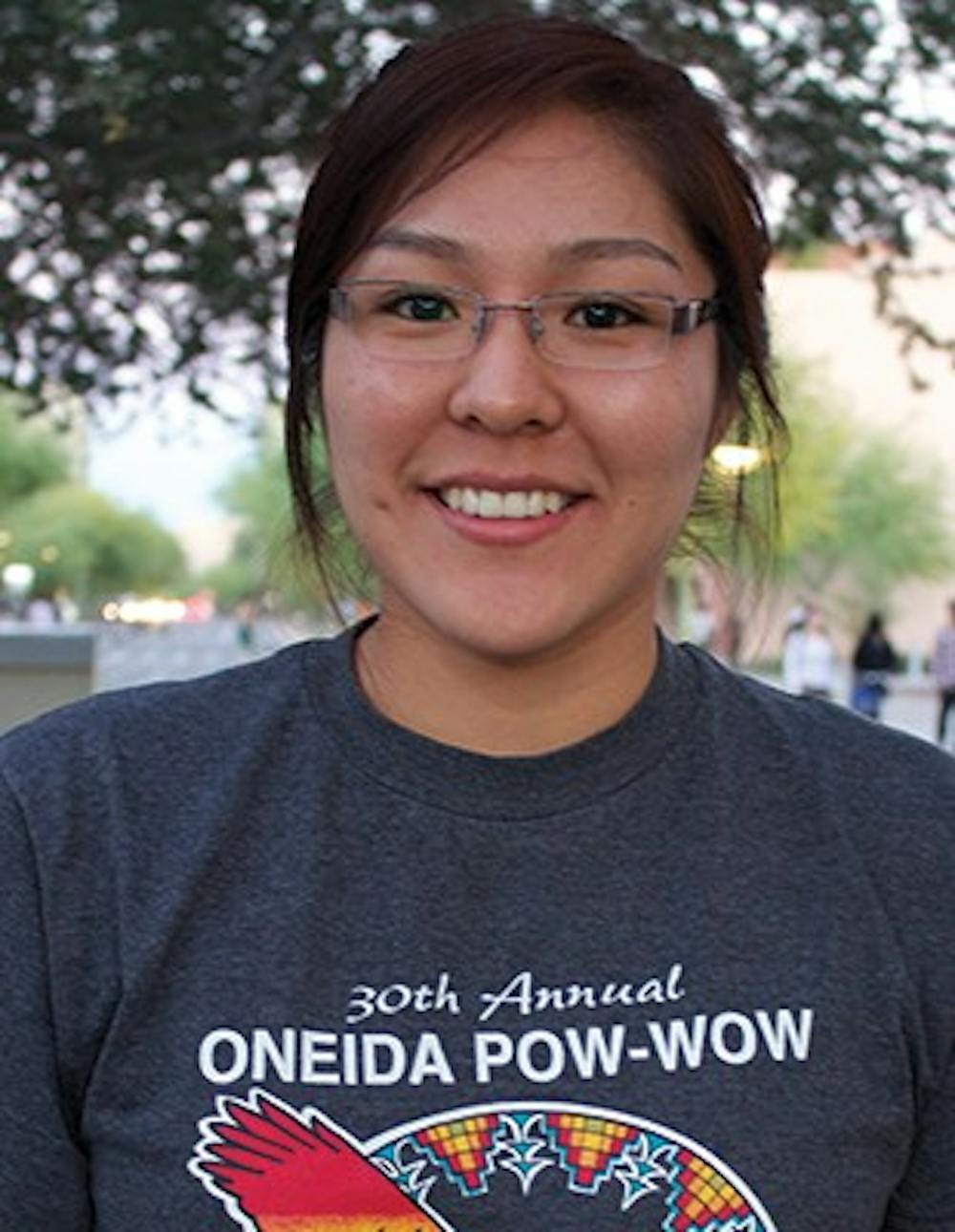

Dakota Yazzie

Secondary English education senior Dakota Yazzie is soft-spoken but open to discussing her life on the Navajo reservation. Her warm eyes behind thin glasses reveal a deep love for her homeland and the people there.

Yazzie comes from a more ceremonial background. She says she grew up attending "squaw-dances" — ceremonies also known as war dances that usually occur between the first rains in July and the first frost of winter. Yazzie also had a ceremony held for herself, called a Kinaalda.

A Kinaalda, Yazzie explains, is a coming-of-age ceremony that occurs when a girl gets her first menstrual cycle.

“I couldn’t shower for four days and I had to wear a buckskin in my hair to school,” she says, reminiscing. “There’s one of those four days when you stay up for the whole night and just sing songs. It’s a really great experience.”

Yazzie says the Kinaalda opens the path for womanhood in a healthy way, as it symbolizes the transformation from child to woman.

Education has always been a large part of Yazzie’s life.

“When I was younger, my mom really stressed education on me,” she says. “She would lock me in a room and make me read a book. I was so upset at her with that, but it really had an impact on me.”

Yazzie originally went into the journalism program to be a voice for Native Americans, but she says she felt that she could make more of a difference by being a teacher.

“I’m trying to be an educated Native American, someone who will enforce change on the reservation,” she says. And even with this goal in mind, Yazzie says she has faced much hardship and stereotyping in coming to school.

The Health Status Assessment reports that 26.9 percent of Navajo County has a high school diploma. The assessment also shows 39.8 percent of Navajo County has some college, whether that ended with an associates degree or no degree at all.

The smallest portion of Navajo County educational attainment is that of a bachelor’s degree or higher, which is reported at just 14.1 percent.

Students of the Navajo Nation make up the largest portion of Native American students attending ASU. According to statistics published in a diversity report put out by ASU titled, “Inspired by Our Elders: Leading with Conviction at ASU,” American Indian student enrollment has remained around 1,400 for the past seven years.

“I get a lot of: ‘You’re Native American, you got into school easy because of affirmative action,’ but I worked hard to get into college,” Yazzie says. “It feels like we’re always proving ourselves in our classrooms, I feel like I’m always trying to prove myself because of my ethnicity. It’s rough but it’s just something we have to deal with.”

One of the biggest things Yazzie says she would like the federal government to help with is protection from outside companies who want to utilize the land. Yazzie says that an outside company has tried to create a gravel pit on the reservation where her grandmother lives in Shadow Mountain.

“It’s really frustrating because those are sacred sites,” Yazzie says. “My grandma is 90 years old, she’s lived there her whole life. I think the federal government should be more involved in protecting Native American land.”

Yazzie says she thinks that because the Navajo Nations is such a young government, large corporations try to take advantage of that without thinking of the long-term effects.

“We’re not trying to say ‘leave us alone,’ we’re trying to say ‘respect us, respect that we’re here and we’re trying to move forward too,’” she says.

Incidents such as these cast non-Natives in a bad light, Yazzie says. She adds that she believes that many Native Americans on reservations are opposed to non-Natives coming onto the reservation and trying to change things.

“If you look at the history between Native Americans and the rest of society, it’s not really good," Yazzie says. "What we learn is that we’ve been screwed over a lot of times by the federal government and I think young Natives see that and they think they’re bad people.”

One of the best examples of conflict between Native Americans and the federal government is Colonel Kit Carson’s attack against the Navajo. The film, “The Long Walk: Tears of the Navajo,” places you in the thick of it.

The strategy was impoverishment.

“You burn their hogans, you burn their fields of corn, you slaughter their herds if you get your hands on them,” the film’s narrator says. “You just destroy their property and make it impossible for them to subsist.” This “scorched earth campaign” was a popular strategy, as General William Sherman would later lead a similar tactic in the South of the United States.

According to the film, Navajos began to surrender in large numbers upon promises of food, clothes and shelter. But the second phase of this strategy was already in effect; it was one of isolation. For this, Carson and his pack marched every Navajo they could get to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. “The Long Walk,” as the Navajo call it, was a hike over rough land with many lives lost along the way. Here they remained until a treaty allowed the Navajo to return to their designated lands, including the Four Corners area.

The history is a bloody one. It is settler’s colonialism at it’s finest.

Yazzie says the fact that history is being taught in such a slanted way really deepens the separation between reservations and the rest of the country.

“It divides Natives from non-Natives because we’re looking at somebody who’s not Native and we’re like, ‘They’re going to screw us over in someway,’” she says. “If you’re stuck on the reservation and you see it that way, you’re going to see it that way for the rest of your life.”

To Yazzie, Manson, Sieweyumptewa and Hemstreet, the solutions to the problems require a great amount of work by their generation to enact change in a society embedded in tradition. Yazzie says the reservation’s society is “caught on their old ways.”

“They’re not seeing that there’s a divide here, it’s like it’s their way or no way at all,” she says. “It’s great that they’re trying to keep the traditional ways, but realistically we’re moving forward and there’s no avoiding that.”

But change and progress start with students in school.

“I want to speak to Native Americans in the ASU community: The reservation needs them, they need them to recognize that they’re part of this community,” Yazzie says.

There’s a small catch in her voice, a dignified yet pleading call to action, as she says: “I just want them to really reflect on what it means to be Native American. I just want all Natives to come together and try to improve home because I really don’t want to let go of my culture or my traditions.”

Reach the writer at mamccrea@asu.edu or via Twitter @mackenziemicro