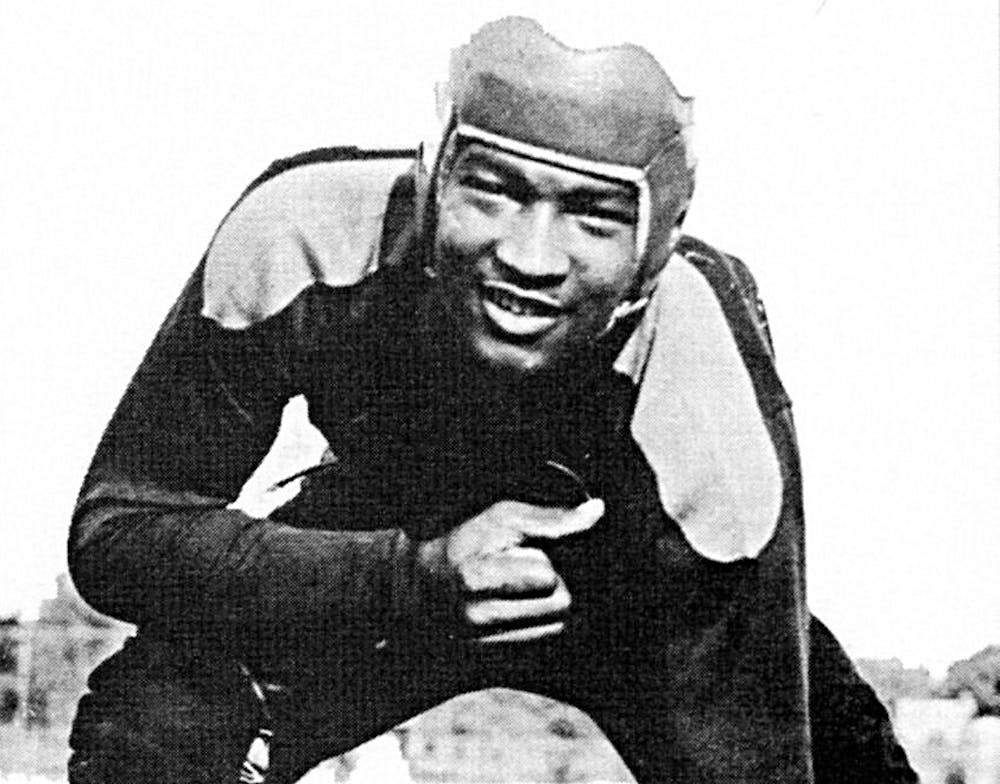

In 1937, during Arizona State Teachers College’s homecoming festivities, a new addition would be made to the Bulldogs' starting lineup. His name was Emerson Harvey, and he held the distinction of being the first black varsity football player in ASTC, now ASU, history.

Harvey came to ASTC as an industrial arts major. According to university archivist Robert Spindler, Harvey started his post-secondary education at Sacramento Junior College in California, but was invited to ASTC to play for the varsity football team.

“There was a man named Tom Lillico, who was formerly on the Bulldogs football team in the early 30s,” Spindler said. “He was hired to serve in a capacity called graduate manager for athletics at the Teachers College, and his role was in recruiting quality athletes to come to the Teachers College in those days. Lillico met Harvey in California and encouraged him to play football here.”

Harvey’s status as the first black varsity football player at ASU was seemingly a non-issue to his teammates. Spindler stated that he was treated well by his fellow athletes and coaches. Despite this, he still faced issues created by Arizona’s Jim Crow laws, which were still in full effect in the late 1930s.

“In 1937, the Arizona State Teachers College did not allow blacks to eat in their dining halls with the white students or to share living spaces in the dormitories of the Teachers College,” Spindler said. “As a result of Harvey’s attendance at the school, over time those rules were in fact relaxed.”

Spindler added that despite the Bulldogs' acceptance of Harvey, he was still the subject of harassment by opposing teams.

“Harvey received threats and taunts from the players on the opposing teams in those days.”

Harvey also could not travel with the team to face schools in Texas, where black athletes were not allowed to compete alongside white athletes.

“If you had a black player, you couldn’t play on a field in Texas,” Spindler said.

Spindler credits Harvey, as well as the Teachers College’s athletic director Rudy Lavik, for starting a “process of change” which led to the integration of schools in Texas as well as the other schools in the southwest.

“What you really see is the beginning of change and the beginning of advocacy on the part of athletic director Lavik that was precipitated from Harvey’s competition for the Teachers College,” Spindler said.

Victoria Jackson, Ph.D, a lecturer at ASU in the school of historical, philosophical and religious studies, stated that one of the more significant factors of Harvey’s story is it’s timeliness compared to other schools in the United States.

“It’s surprising in that it’s so early,” Jackson said. “Arizona has a southern heritage as much as it’s a western state, so a lot of the people who had migrated west brought the ideas and racial practices of the south with them as they moved to Arizona.”

Many of Harvey’s challenges were shared among black athletes who broke the color barrier. According to Ron Cox, Ph.D, an ASU professor of African and African-American studies, activities such as even finding a place to sleep during road trips to other schools proved difficult.

“Black players, when they went to play an away game, a lot of them couldn’t live in the hotel with the team,” Cox said. “So they had to make arrangements to live with a family of color.”

Like Harvey, many black athletes were not allowed to take the field in segregated states. College sports had an unofficial “gentleman’s agreement,” stating that if a school were segregated, any schools visiting would not bring black athletes with them.

“Those gentleman agreements are the same thing to me as Jim Crow laws,” Cox said.

Cox added that many integrating schools may not have been looking to do what is now considered morally or ethically right, but rather to gain an edge in competition.

“Americans like to win,” Cox said. “They compete to win.That’s what we use sport for to a great degree in our country. It teaches us how to compete.”

Cox went on to mention that no matter the reasoning taken by these schools, stories of athletes breaking the color barrier are significant because of the broadened visibility of black athletes.

“They got on a bigger platform,” Cox stated. “The media is a platform. You got a chance to see what they could do.”

Reach the reporter at jdarge@asu.edu or follow @jeffdarge on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.