Advent Diamond, a startup by ASU scientists, is attempting to monetize diamonds through their electrical properties.

The research team behind Advent Diamond is collaborating with NASA to create electrical components made from diamonds they grow in a lab, with the intention to commercialize the technology.

“We’re getting close to making the first (diamond) power transistors, more or less, in the world,” said Robert Nemanich, a physics professor at ASU and co-founder of Advent Diamond.

Normally, transistors are made from silicon introduced to impurities in a process called "doping," but Nemanich said the semiconductor has its limitations.

“It only takes a small chip of diamond to do what a much larger piece of silicon would need to do it,” he said.

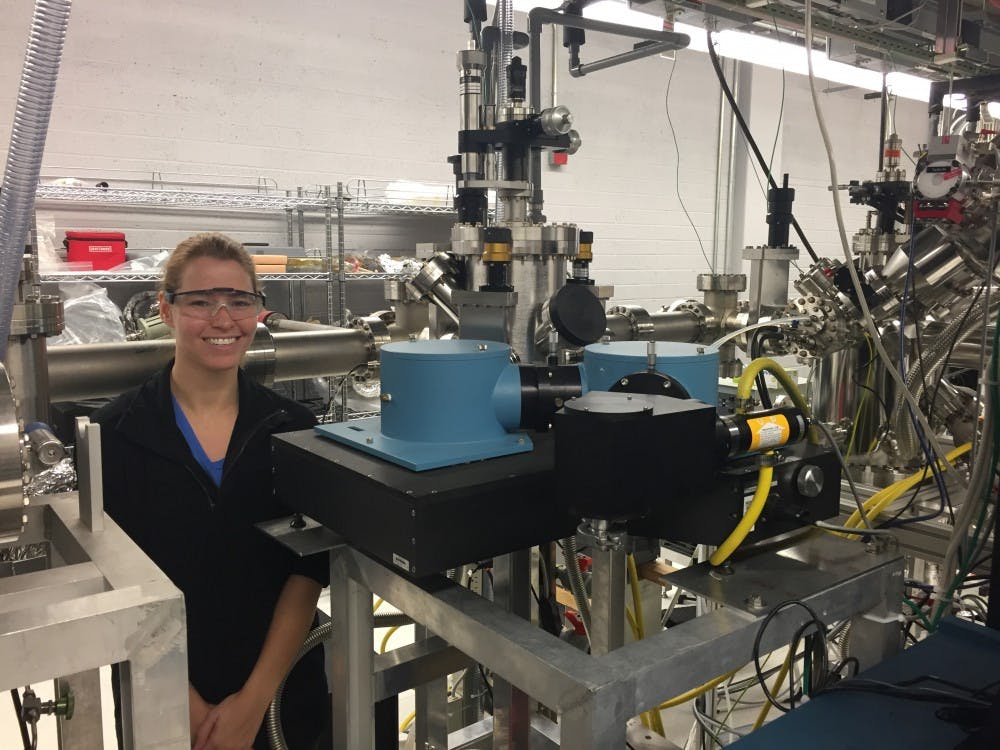

Brianna Eller, the professor leading the startup, said the limitations do not stop there. She said that silicon does not function very well in extreme conditions.

“Diamond is great for high temperatures, diamond is great for pressure …. It’s just a very robust material,” she said.

Still, Eller said, competing against silicon could be difficult.

“Silicon is such an established competitor in the market,” Eller said. “It’s so mature that it’s really, really cheap.”

She said the overwhelming prevalence of the element means its weaker durability does not impede its usage. When silicon chips break, Eller said they can be cheaply replaced.

“We want to focus on the areas where silicon can’t compete,” she said.

One such area is space, and more specifically Venus, Eller said. The team said NASA confirmed that they will contract ASU’s research team to make electronics for a Venus rover.

“The surface of Venus is so hot that anything you put down there burns up really quickly,” Eller said.

She said Russia has sent a probe to Venus, but the conditions there destroyed the instrument in a matter of seconds.

Despite the challenges, researching Venus could provide scientists with information about climate change, Eller said.

“There’s kind of this idea that Venus is what the Earth would be post global warming,” Eller said.

Erik Asphaug, a professor at ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration, said that many technological challenges arise in space.

“You can’t just translate a device built in a one bar atmosphere on earth at 70 degrees Fahrenheit and then expect it's going to work in much hotter or much colder temperatures in vacuum,” Asphaug said.

He said this makes developing space exploration equipment laborious and rare.

“Places like ASU, that do develop instruments in-house … it’s not something that you just do some day,” Asphaug said.

NASA tends to use tried-and-true technology, Asphaug said. Still, he said there is room for improvement.

“We take it for granted that heat is just going to dissipate into the air or radiate away.” Asphaug said. “In vacuum, there is no air to convect the heat away.”

Eller, Advent Diamond’s cofounder, said diamond’s extraordinary heat capacity makes it perfect for these conditions, and the applications do not stop there.

Because diamond chips are lighter-weight and can carry more voltage than their silicon counterparts, Eller said they could be used in drones and for geothermal energy drilling.

She said ASU will benefit from her startup, as they own much of the business’s foundational intellectual property.

Advent Diamond's collaboration with ASU has allowed Eller to grow her own diamonds in a lab, which comes with its own benefits, Eller said.

She said the chips can be produced for about $3. Although this is much more expensive than silicon, she said it is surprisingly cheap and avoids ethical concerns.

Eller said what the researchers are growing in the lab is chemically identical to what would be mined, adding the only difference is that "you don’t have to exploit African children to get it out of the Earth."

Reach the reporter at chawk3@asu.edu.

Like State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.