Jamal Cadoura has been posting poetry on Instagram since 2015. The 25 year old Michigan-based writer is known online as @Writingtoinspire, and typically posts simple black text over a white background, but he allows himself room to experiment with different designs.

Every post explores a new emotion, diving into feelings of emptiness, imperfection, picking oneself up by the bootstraps and more.

“A way for me to vent and a way for me to heal was to write what I was feeling, to allow my feelings to materialize in a different way, to give credence in a way that I was unable to,” Cadoura said. “And I've always noticed that no matter what you have in life, the things that will stand the test of time have been words.”

He said he wants his Instagram to stand as a virtual museum where users can explore any post on any particular day.

“You can see the relics of pain that I've overcome, the portraits of beauty that I could be experiencing on a daily basis, all of these things are on full display and I'm proud of them,” Cadoura said. “I want to put them out there because the point of art is for art to be seen.”

Blunt line breaks, emotions expressed in a handful of words and a thought that fits within a few lines pasted over an aesthetic background; these qualities make up the art form dubbed “Instagram poetry.”

Instagram poetry is reshaping the way people view and approach the medium. It is setting a mold for a new, highly accessible means of millennial and Generation Z communication, acting as a voice to those who feel underrepresented and existing as an outlet people can claim as their own.

Over the past few years, the new genre has risen to the top of publishing charts. As poetry consumption increases with great success from Instagram poetry collections like Rupi Kaur’s “Milk and Honey” and R. H. Sin’s “Whiskey, Words & a Shovel I,” prove social media’s significant impact on the consumption of information and published works.

The number of adults reading poetry within the past decade has nearly doubled, according to a survey conducted by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Young adults between the ages of 18 and 24 have the highest increase in poetry consumption rising by 8.2% in 2012 to 17.5% in 2017. Adults between the ages of 25 and 34 increased their consumption by 6.7% in 2012 to 12.3% in 2017.

Though Instagram poetry has a noteworthy fanbase, the art form remains a controversial subject in the poetry community. Some poets point out the differences between Instagram poetry and other forms of written art, contrasting qualities and drawing strong opinions. Some are even calling for Instagram poetry to be disassociated with traditional forms of the craft.

Contemporary poet Kristen Brida said the key impact of Instagram poetry, which is reflected in its structure, is immediacy.

“For instance, short lines (and) very casual language,” she said. “I personally view it as a kind of quote that floats around or a saying, and then separated by really short line breaks and still has a very simple grammatical structure to it despite the line break.”

Brida said Instagram poetry's simple structure provides a form of immediacy. When visuals and feed aesthetics come into play, those details can further drive the evolution of poems online, she said.

“I don't think the aesthetic necessarily interacts with the poem, but I think it kind of fits with what the genre of Instagram is about,” she said.

When considering the cultural phenomenon of Instagram poetry, it’s hard to overlook the work of Canadian Indian poet Rupi Kaur. Her debut collection, “Milk and Honey,” has spent 103 weeks on The New York Times Trade Paperback Best-Seller list since its inception, and her second collection, “The Sun and Her Flowers,” has spent 26 weeks on the list at time of print.

Kaur, @rupikaur_, has 3.7 million followers on Instagram. Her posts range from her poem history, new and old, to photos of herself. Each post creates a consistent theme on her Instagram layout.

On June 30, Kaur shared a poem written in all lowercase letters, from page 180 of “The Sun and Her Flowers,”

“they should feel like home

a place that grounds your life

where you go to take the day off

the one — rupi kaur.”

The post reached over 200,000 likes.

But Instagram poetry doesn’t stop at the success of Rupi Kaur.

Canadian Instagram poet Atticus, @atticuspoetry, currently has 1.2 million followers on the app. He keeps his identity anonymous, wearing masks during public readings. He posts poems on his feed with small, black font over white backgrounds, or white on black backgrounds.

A poem he posted on Aug. 7th, 2019,

“I didn’t see her love

I felt it

As plainly as the sun

ATTICUS.”

The poem received nearly 40,000 likes in two days. The New York Times bestselling poet has two books under his belt.

New York City-based poet and activist Cleo Wade, @cleowade, published "Heart Talk: Poetic Wisdom for a Better Life," a bestselling collection of poems. Marie Claire, an international monthly magazine, named her one of America's 50 most influential women. Her second collection of poems, “Where to Begin,” is set to release Oct. 8, 2019.

Wade’s popular posts are self-help oriented and oftentimes gather over 10,000 likes per post.

In capital letters and scrawled writing, Wade, on July 19, 2019, shared;

“I believed I could —

Mostly because constantly

thinking I couldn’t got

Really boring after a

While.

Love,

Cleo.”

The post received over 13,000 likes with comments like “Amen!” by @jlhgardner and “Needed to hear this *octopus emoji*” by @the.anxious.poet.

Brida said Instagram poetry has the ability to evoke genuine feelings because of the relatable and accessible language used. It allows readers to reflect and insert their own personal history into what they’re reading.

“When teaching poetry, teachers don't necessarily encourage students to insert themselves into the poem,” Brida said. “What are they feeling? What are they experiencing? Whereas I think with Instagram poetry, it actually allows more of that.”

Through its popularity with poetry lovers, Instagram poetry has received a wide amount of criticism from poets and literary critics.

Poet Elizabeth Deanna Morris Lakes is a co-host of The Smug Buds podcast, which is devoted to discussing topics ranging from creative writing to gender (including an episode discussing the qualities and criticisms of Rupi Kaur).

When it comes to considering Instagram poetry a true form of the craft, she said she draws a line.

She said a lot of poems written by Instagram poets do not quite fit her definition of what a poem is. She considers the length of Instagram poetry a part of why it should be its own genre, separate from other forms of poetry.

“With short things, you can only edit and revise so much,” Deanna Morris Lakes said.

“It's written fairly quickly, because it’s being produced really quickly,” she said. “I think Instagram poetry sort of falls within that inspirational Instagram post area where it's like image texts, supplemental photography, drawings or whatever along the side.”

Deanna Morris Lakes said that a large part of writing poetry is revision.

“There is a craft that goes into poetry that does involve revision,” she said. “I think that a large part of writing poetry is revision, so I think that if you're just producing and not revising that isn't really fitting into the genre in the same way.”

English Literature graduate student at ASU and poet Natasha Murdock said she believes that no work of art is the same, and though Instagram poetry is different from literary poetry, it should fall under the same category.

Murdock was browsing the poetry section of her local, suburban Target and was taken aback by a literary book she saw on the shelf — “If They Come For Us” by Fatiah Asghar, a poetry collection that discusses topics of nationality, age and gender through the experiences of a Pakistani Muslim woman living in America.

Murdock said the book was presented in a way that if readers liked “Milk and Honey” by Rupi Kaur, they would also like “If They Come For Us.” She said a critically renowned book like that might not have been accessible to people in the suburbs without Instagram poetry.

“Most of them would never even know that book existed, and that happened because of an Instagram poet,” Murdock said. “If you want to stop calling it poetry? Fine, but you're throwing a bunch of readers away. It's worth the risk to me because we're risking nothing.”

She said if anything, people are risking getting more people to read poetry. The mechanism of questioning poetry and the boundaries of the craft is something writers, academics and others should constantly be doing, Murdock added.

“But when the answers limit what poetry can be or become exclusionary, it's hard for me to believe that we've answered the question correctly, or that we're asking the right questions to begin with,” she said.

Murdock said that in classes that teach poetry, teachers often give students poems to read that are from generations before them that cover feelings or topics they have yet to and perhaps never will experience.

“Especially in high school, or even in literature classes in college, introduction to literature classes use really outdated poetry,” Murdock said. “I'm not saying we should or shouldn't return to the classic literary canon, but maybe we can look at Instagram poetry as a gateway for people who would never otherwise read poetry ever.”

Brida said Instagram poetry is a starting point for those interested in reading or writing poetry.

“I think that's what a lot of maybe more literary poets forget, is that to get people to read poetry or to understand the nuance,” she said. “You have to start with something that they can relate to.”

Instagram poetry has the potential to speak to younger generations, Deanna Morris Lakes said, and make them feel more emotions they may not understand yet.

“Part of the reason people it resonates with people so much is that (Instagram poetry speaks) in ways I would consider to be cliches a lot of the time,” she said.

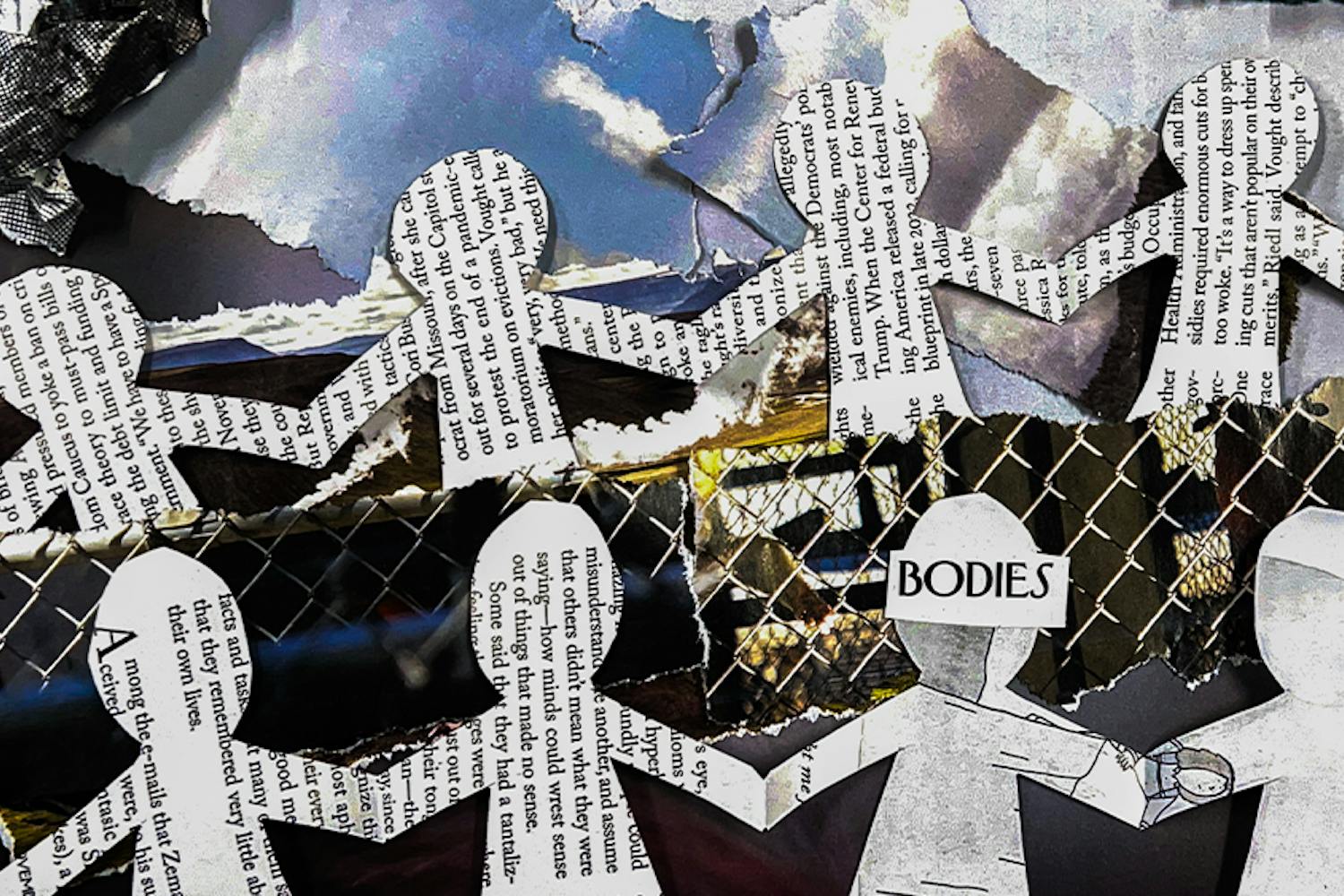

The survey conducted by the National Endowment for the Arts showed that poetry readership has increased significantly for those who fall under different ethnic backgrounds. The number of people who reported reading poetry doubled for groups like African Americans and Hispanic Americans, and some almost tripled for groups such as Asian Americans.

The medium also has an opportunity to act as an emotional outlet for a wide audience, an art form that people can take and alter to fit their own unique identities.

Murdock said that in the era we live in, surrounded by a culture “based on colonialism and racism and sexism and the abuse of so many different people,” a lot of individuals are feeling a heavy weight of emotions.

“I don't think as a culture we're taught very well how to communicate those feelings,” Murdock said. “So we're scrolling through Instagram or Twitter and we see a little post and it catches our eye. It says something and it expresses something that maybe we couldn't express ourselves.”

Instagram poet Cadoura said that Instagram not only provides him a platform for artistic expression, but also helped him discover and understand the fluidity of what poetry can be online.

“This is art and this is life, things evolve and things change and it feels even better to be a part of this wave and to be an innovator of this field,” he said. “To say ‘Hey, this is what you can do.’”

Cadoura said that he wants his readers to know that they are not alone in their struggles, and that there is “a universal struggle that interweaves all human beings.”

One of the main reasons he posts his poetry online is to connect with people from different places and backgrounds, individuals he may never have crossed paths with if he did not share his writing on Instagram.

“The beauty in art is seeing the way it binds all of us together,” he said. “I wanted to show people that there is hope in the struggle. There is a voice out there that's calling to you and that will bring you back home to yourself.”

Reach the reporter at jlmyer10@asu.edu or follow @jessiemy94 on Twitter.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter.