Tempe police officers will now carry Naloxone, also known as Narcan, to help Tempe Fire Medical Rescue continue the fight the city's opioid epidemic.

The initiative was made possible through a $2 million grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

For the next four years, the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice will track data to see if the initiative is effective at combating opioid abuse in Tempe, according to a city of Tempe press release.

Narcan is a nasal spray that is used as a treatment for people experiencing an opioid emergency, which is when individuals experience difficulty breathing and may not able to respond to others.

Sgt. Robert Ferraro, president of the Tempe Officers Association, said after Gov. Doug Ducey declared a public health emergency for opioid abuse in Arizona, the city of Tempe decided to find a way to equip police officers with Narcan for the wellbeing of the Tempe community.

Tempe applied for the grant that offered an opportunity for communities to equip first responders with Narcan and also provide aftercare for people after they have been administered Narcan, Ferraro said.

Providing care after the incident is what will ultimately save lives, Ferraro said.

“That was really the attractive piece to this grant because it would allow us to partner with a nonprofit that specifically deals with these types of addictions and suicide prevention, and then ultimately partner with ASU to evaluate the grant, how it's implemented and ultimately if it works,” Ferraro said.

With this new program, Ferraro said after an individual who received Narcan goes to the hospital, they will have a crisis worker who becomes a navigator for them and shares resources. Before, people would get lost in a shuffle due to a lack of communication and not always receiving help.

"It's the follow up phone calls — it's a constant attempt at trying to get this person to accept help,” Ferraro said.

Andrea Glass, assistant chief for Tempe Fire Medical Rescue, said the grant will also fund a full-time police employee to administer the program and train officers, and each officer who administers Narcan will report the individual to La Frontera EMPACT, a crisis and community health behavioral provider.

Data collected by Tempe Fire Medical Rescue has been important for the city of Tempe to assess who in the community needs help, Glass said.

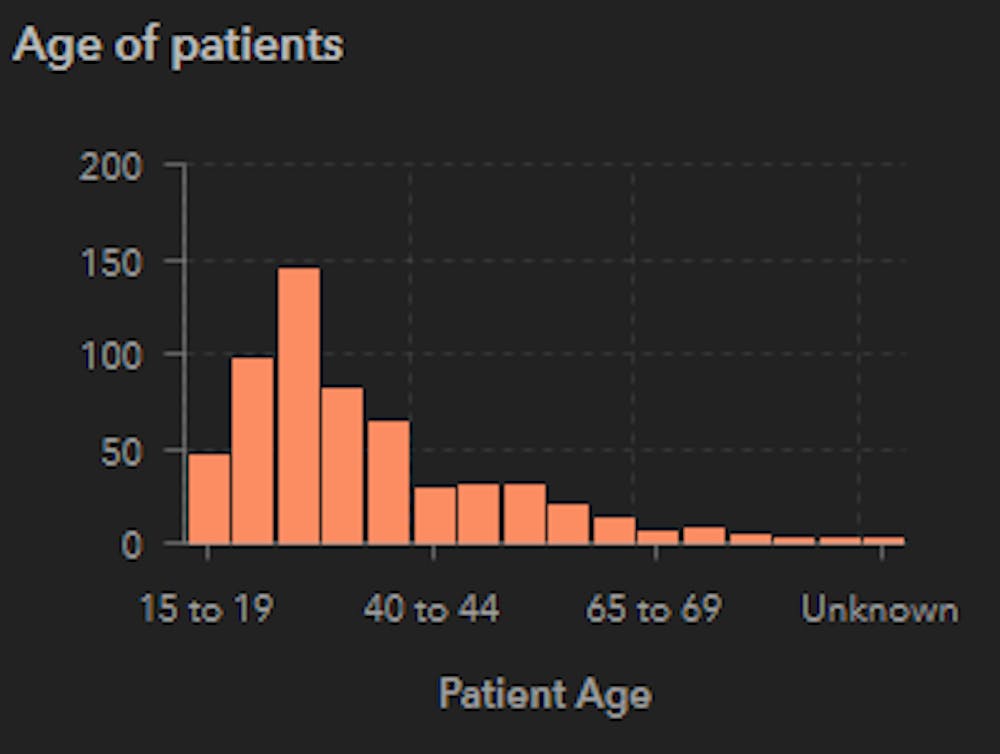

Using data collected since 2017, Glass said efforts have been geared toward the age groups that show the most usage, particularly high school students since the age range with the highest opioid abuse in Tempe is 19 to 29.

Graph of the average age of patients who have abused opioids from the Opioid Abuse Probable EMS Call Dashboard from the city of Tempe. Captured Nov. 12, 2019.

Mike White, professor and director of the doctoral program for the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, is leading the research for the program.

He said some of the research will involve interviewing people about their experiences with the new initiative and how police officers’ perception of drug abuse has changed over time while participating in the program.

"The goal is to get folks whatever services they need,” White said.

White said whether it's substance abuse treatment, educational services, employment or housing, the goal of the program is to improve the quality of life for people who have abused opioids so that they don't experience another overdose.

The city of Tempe is also trying to find the best strategies for informing ASU students in the 19 to 29 age range about the dangers of opioids that are sometimes cut with fentanyl or carfentanil, Glass said.

“People think that they're just getting a normal Vicodin or a normal Oxycodone,” Glass said. “What they don't understand is the people who are actually making these drugs are making them with the more potent form because it's cheaper to make it, so they often are overdosing unintentionally.”

Glass said people in the community often abuse opioids after recovering from normal injuries or take leftover pills from other medical procedures to aid with sleep or stress. However, the data is only one part of solving the opioid problem.

“We can have all the data in the world, but unless you have the resources, education and know where you can go to get help, it's not going to make a difference,” Glass said.

Reach the reporter at tmlane3@asu.edu and follow @tmflane on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.