Editors Note: This story contains strong language that has been censored throughout.

I didn’t know I was Asian until I was 7 years old and got in trouble at school for calling somebody a “c---k.” Let me explain.

My parents are both from a small southeast Asian country called Laos. My dad came to the United States as a refugee during the '70s, whereas my mom came sometime during the late '80s. Long story short, they met at work, got married and had me. According to my mom, "it all went downhill from there."

I blame my Asian identity crisis solely on my parents — they just assumed that I automatically knew I was Asian, but they never told me outright. For those of you who don’t know me, I am what you might call "ethnically ambiguous." You’ll see me and run through all the different ethnicities in your head and try to guess the correct one, but most people don’t. It’s OK, I don’t blame you — I’d guess wrong too.

On top of that, my parents didn’t really monitor the TV shows and movies that I watched. In fact, they encouraged me to see movies like "Die Hard" or "Predator" simply because they were fun to watch, and oh man, were they right! Young me was especially obsessed with kung fu movies: “Five Deadly Venoms,” “Enter the Dragon” and “Drunken Master.” If it has been referenced in a Wu-Tang Clan song, chances are I’ve probably seen it.

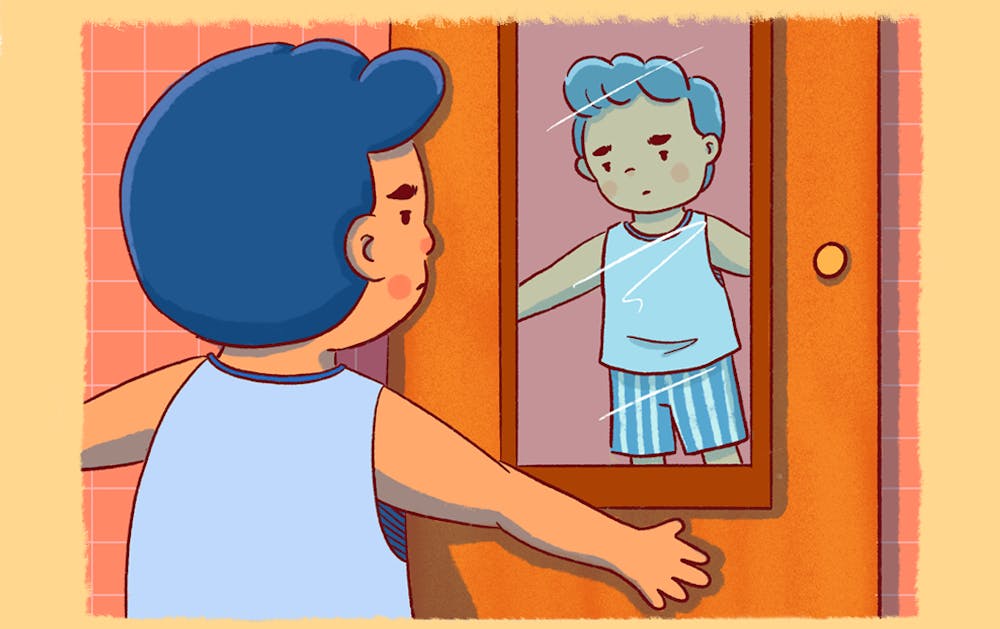

My dad always told me that these were “Asian movies.” Because of that, I would see stars like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Jet Li and immediately associate them as the archetype for Asian people. While I was enamored by these action stars and continuously practiced every single one of their moves, I was also overcome with sadness because I felt like I could never be like them — after all, I didn’t look like them. My skin was fairly darker than theirs, my eyes didn’t resemble theirs and my hair didn’t look like their hair. It was then when I was about five years old that I thought to myself, “Man, I wish I was Asian!” and carried this grudge with me.

I was born and raised in San Diego, California, which has a pretty sizable Asian population. Therefore, I went to school with many Asian kids. I always looked at them with a sense of jealousy and infatuation because, in my young mind, they had a connection to my idols that I never thought I would be able to attain. I thought about this a lot, but things came to a breaking point one day in third grade.

There was a kid in my class named Randall who kept bothering me about my new pack of Crayola colored pencils. Now, I want to take a moment to say that I hated Randall, but that hatred probably stemmed from him being the perfect Asian kid I didn't think I could be.

I was working on a very important drawing of George Washington for my social studies project when Randall and his group of flunkies surround my desk. "Hey Timothy, let me borrow a red!" he called out.

Now, this was a fresh pack of colored pencils. The top of the lid wasn’t even marked with the colored dots that would collect over time. All the pencils were pristine, and I wanted to keep them that way.

“No, I’m not letting anybody use these," I told him. "Go tell your mommy and daddy to buy some."

Randall wasn’t having any of it, so he made a grab for the box, but he wasn’t quick enough; I managed to keep it out of his reach. However, one of his friends snuck up behind me and seized the box from my grasp, taking out the red pencil and tossing it to Randall.

I don’t know what came over me. Maybe it was the fact that I was tired of Randall bullying me. Maybe it was because I bought those colored pencils with my own money because I was tired of using the pity crayons my teacher provided for the class. Whatever it was, I lost control.

I could’ve swung at him, but instead, I yelled out, "Randall’s a c---k!"

The whole room went silent. You could hear the drop of my colored pencils, but I didn’t even know that what I said was so offensive. I had just heard a character say that word in the Bruce Lee biopic “Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story.” All I knew was that Randall started crying, and I was sent to the principal's office.

My dad came into the principal’s office and sat down next to him. While he was calm on the outside, I could feel the anger radiating from his body. They started by talking about me, and how they were both surprised to find me in this situation because I was normally a good student — I always raised my hand, never talked back to teachers and was even the type to stay after school to help the teacher clean up. Wait, was I a teacher’s pet? Anyway, the conversation then shifted to what landed me there in the first place.

"Well, Timothy said a racial slur," the principal said.

My dad didn’t say anything. He just looked at me, and it was at that point I knew I messed up.

“What did he say?" my dad asked.

“To be frank, he called another Asian student a c---k.”

I remember the look on my dad’s face going from anger to confusion and then to embarrassment.

“I’m so sorry, I don’t know why he would say that," he said. "My wife and I have raised him better than that. He certainly didn’t get it from us; my best friend is Asian.” Looking back on it now, it sounds ridiculous because my dad is literally Asian.

The ride back home was silent for the most part. I couldn’t bear to look at my dad because I wasn’t sure if he was still angry at me, so I just looked out the window watching the city pass by.

“Did you really call another Asian kid a c---k?” my dad asked.

“Yes.” I still wasn’t looking at him.

“I know you were angry, but that doesn’t make it right," he said. "People called me that all the time in high school. It’s a hurtful word to us.”

Finally, I faced my dad. “What do you mean? We’re not Asian.”

My life flashed before my eyes — my dad swerved the car, and I thought we were going to get in an accident. Luckily, he regained his composure. “We are Asian! Your mother and I are from Laos!”

Anything my dad said after that went out the window as I became overwhelmed with happiness. I was really Asian! I was like Bruce Lee, Jet Li and Jackie Chan. I could be like them.

I was so happy that once my dad pulled into the driveway, I hopped out of the car and ran into the house. My mom sat on the couch with her arms crossed. I imagined she practiced more than 1,000 lines once she heard the news of my trip to the principal’s office. She ran through every scenario in her head, every excuse I would’ve given — the amount of crying I would’ve done couldn’t faze my mom. However, nothing could have prepared her for what happened next.

I rushed into the house and jumped into her lap. She was about to speak when I interrupted and said, “Mom! Guess what? I’m Asian!” Like my dad, her look went from anger to confusion. That confused look carried on to my dad as he entered the house. It didn’t matter to me, though. I left my mom’s lap and went into the den. I turned on the TV, popped in my DVD copy of “Fist of Legend” and did my daily routine of copying the moves displayed in the movie.

I wish I could tell you that I rode off into the sunset with a newfound sense of identity, but I’d be lying. Growing up, it wasn’t enough for me to know that I was Asian— I still wanted validation from the Asian peers around me.

However, that acceptance never came.

A teacher of mine, who was Filipino, once said to me, “you won’t ever fit in with the Asian kids because you don’t look or act like an Asian person.” It was a very messed up thing to say to a 13-year-old, but it was my reality.

That chip on my shoulder that I thought I had gotten rid of once I learned of my ancestry never fully went away. That is until I saw a little show from the '90s.

Confession: I never saw a single episode of “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” until I was in high school. One day, my friend was kind enough to let me borrow his series collection, and over the course of a month, I experienced the pinnacle of sitcoms. However, there was one episode that stood out above the rest.

In season four, there is an episode titled “Blood Is Thicker Than Mud." In the episode, the main characters, Will and Carlton attempt to join the same fraternity at their university. They go through intense hazing, and Carlton has it worse than any of the other pledges. Toward the end of the episode, Will is accepted into the fraternity, but Carlton isn't, even though he endured every ritual. He's told that it's because he isn't "black enough" for his fraternity, even though he tried hard to prove himself. Carlton defends himself with a very powerful speech.

"Being black isn't what I'm trying to be, it's what I am," he said. "I'm running the same race and jumping the same hurdles you are, so why are you tripping me up? You said we need to stick together, but you don't even know what that means."

As a teenager who had a very strained relationship with his Asian identity, the idea that I didn't have to prove my Asian identity was something I needed to hear.

I know it may seem ridiculous that this sitcom from the '90s opened my eyes to my identity, but isn’t that the reason why we watch movies? For the same reason that a book could keep us thinking about it even years after we read it? Or why some songs can move us to tears? We find our connections through these pieces.

The episode made me realize that it didn’t matter if other Asian Americans accepted me, and it stopped being about trying to act more Asian because, at the end of the day, that is what I am. My mom and dad are from Vientiane, Laos, and I am their child: that is the only validation I will ever need.

Reach the reporter at txayasom@asu.edu and follow @its_tim_x on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.