Ashley Edison, a member of the Navajo Nation, has spent the past three weeks assisting voters at an early voting drop-off site set up beside a Chevy truck outside the Leupp Chapter House in a small town north of Flagstaff.

"Nobody else wants to be out here doing this," said Edison, a junior majoring in American Indian Studies.

Edison attends her classes remotely on her phone next to the ballot drop-off truck during her eight-hour shifts outside, Monday through Friday. Her grandmother, who is working at the drop-off location with her, helps translate the ballots for Navajo speakers.

This is the first time either of them has worked an election.

"I would have never expected to work with my grandma, but in this case it is pretty awesome," Edison said.

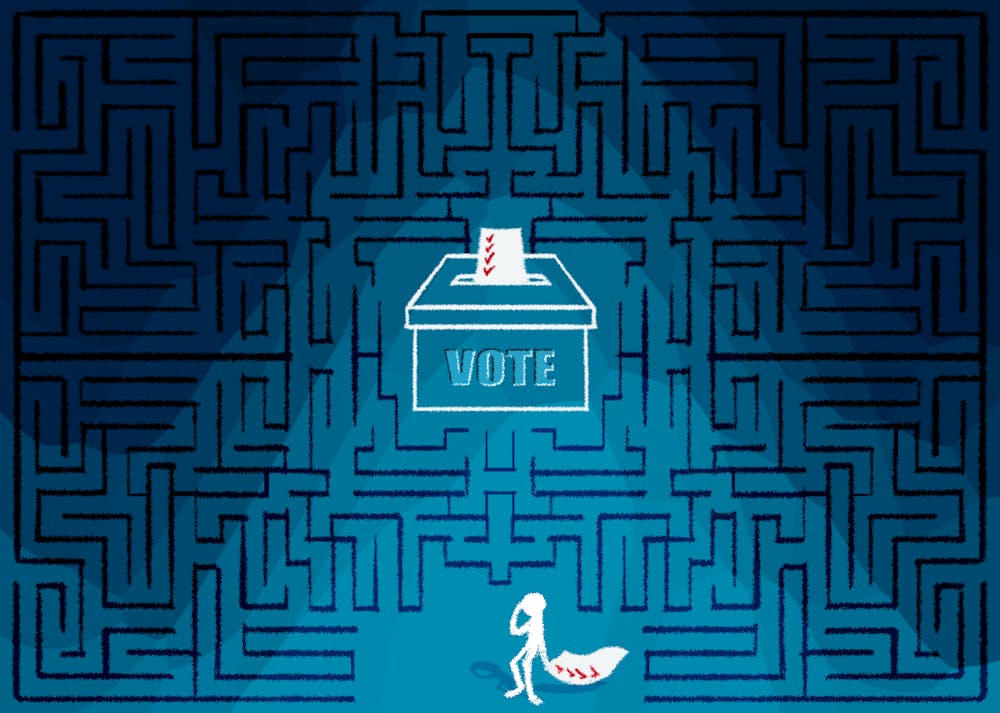

According to Torey Dolan, a fellow with ASU's Indian Legal Clinic and the Arizona Native Vote Election Protection Project, language barriers and remote polling locations are just part of the hurdles Indigenous communities face heading into Election Day.

Indigenous voters on reservations also have to navigate confusing county regulations, issues with identification, and, up until this September, those without a traditional address like ones on reservations were unable to register to vote.

In a Sept. 20 press release, Arizona's Secretary of State's Office announced voters without a traditional address could provide a description of their location, a Google Plus Code or the latitude and longitude of their residence.

According to Dolan, lack of communication between county recorders and tribal leadership is at the center of the confusion.

"Individual counties have a lot of control and discretion on how they administer elections," Dolan said. "Especially when it comes to tribal land, because there's no law mandating that you have to consult with the tribe or that you have to provide equal access on a reservation."

The confusion is only amplified on reservations stretching across multiple county lines and precincts, Dolan said.

In Arizona, ballots cast in the wrong precinct are discarded.

The Democratic National Committee sued the state over this practice, which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled has "a discriminatory impact on American Indian, Hispanic, and African American voters in Arizona."

According to a report cited by the court in its opinion, during the 2016 election Indigenous voters cast ballots outside of their precinct "at twice the rate" of white voters, with "the vast majority" of ballots that election cast outside the correct precinct in Apache, Navajo and Coconino counties were in areas "almost entirely American Indian."

However, the ruling does not repeal the policy. The lawsuit is still not over, with the U.S. Supreme Court agreeing to hear arguments regarding the case.

"That's really a failure on the counties to serve their constituents on the reservation, when they’re not willing to at least consult with the tribal government," Dolan said.

To help voters find their precinct, the Arizona Native Vote Election Protection Project created a user-friendly polling location tool for Indigenous voters.

Dustin Rector, a third-year law student and member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, said he and others a part of the Arizona Native Vote Election Protection Project will be working on Election Day to assist voters on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation.

Rector said on top of helping voters navigate the usual obstacles, they are taking precautions to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19 and to protect voters from possible intimidation.

"I think this is going to be a very interesting year," Rector said. "I don't think there's gonna be a boring moment."

The Arizona Native Vote Election Protection Project is aiming to support voters on reservations that do not have the same resources as surrounding counties.

"The more remote a reservation, the less support there is to provide," said Richard Breuninger, an associate professor of American Indian Studies.

For students living on reservations, access to the internet isn’t a guarantee — a burden shared by students and voters alike, who are unable to access critical information to meet deadlines.

"I've been to the places where my students come from, and I know how far away they are," Breuninger said. "They're there because they have to support family and their elders during the pandemic."

Support is often left up to poll workers like Edison at small satellite voting stations on reservations.

"Go vote and get your voice heard," Edison said. "Not everyone has the opportunity to vote and there are resources out here, such as me and my group who are willing to sit out here all day and wait for ballots."

Reach the reporter at kpirehpo@asu.edu and follow @kevinpirehpour on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.