Carlos Diaz was watching the news when the solution to a problem that’s haunted him for a decade happened to air in the evening broadcast.

About 10 years prior, an officer pulled Diaz over for a broken headlight. And what started as a routine traffic stop, escalated to two sobriety tests – both of which Diaz passed.

Then, officers asked to search his vehicle. Diaz obliged, certain he had nothing to hide. But unbeknownst to Diaz, the butt-end of a burnt joint sat silently under his passenger seat.

It didn’t take much searching in his two-door Mazda Miata for the officers to find the remains of the marijuana cigarette. And soon after, he was escorted to the nearest police station and charged with a misdemeanor for possession of paraphernalia.

The charge clung to Diaz for a decade, pervading every job interview and new opportunity he dove into during this time.

But in April, as the anchor clearly dictated on the TV screen, a dispensary in Phoenix was hosting a free legal clinic for those with expungeable marijuana convictions, and Diaz was among the eligible.

Six months after recreational marijuana sales took effect in January, the courts rolled out a process allowing for those with pending or past marijuana charges a pathway to a complete expungement.

The courts started accepting petitions in early July, and advocacy groups moved to help eligible people navigate the expungement process.

But despite their best efforts, advocates say the opt-in format makes it difficult to reach the people who need expungement most, and differences in legal opinion across county lines still pose significant barriers to a clean record.

Basics of Marijuana Expungement

Voters passed the Smart and Safe Arizona Act, a law legalizing recreational marijuana, in November 2020. The initiative, commonly known as "Prop. 207," included a provision allowing anyone with a charge for possessing, consuming or transporting under 2.5 ounces of marijuana, six marijuana plants or any related paraphernalia the chance to start anew.

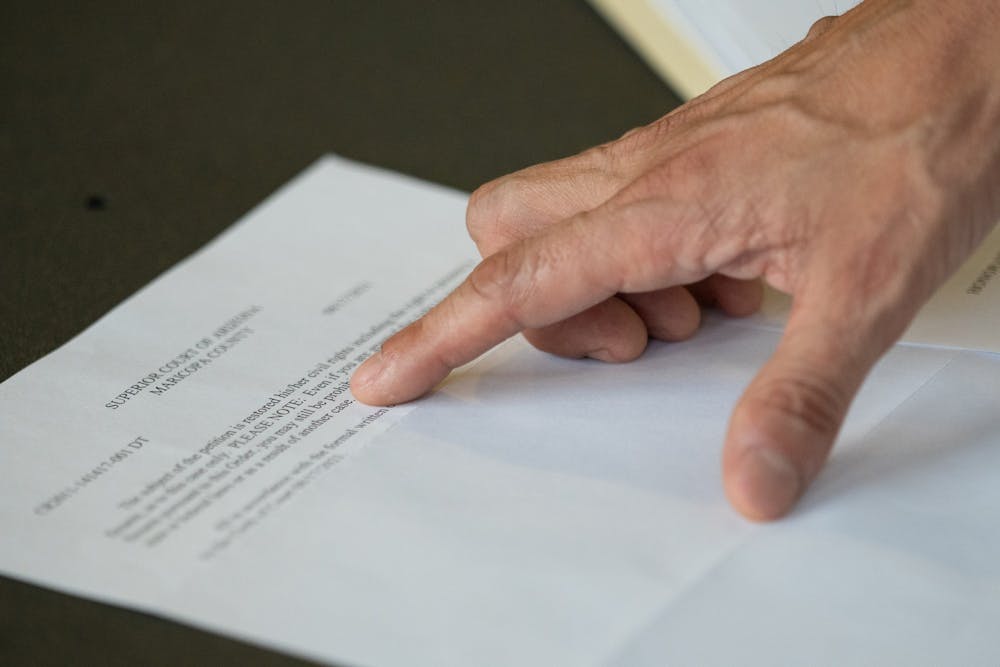

Applicants can provide their information, petition the court and, if successful, see the charge disappear completely, a type of expungement previously unseen in the Arizona legal system. Before the passage of Proposition 207, convictions could only be set aside, meaning the charge still shows up on the records but reinstates civil rights.

Expungement guaranteed by the passage of Proposition 207 reinstates civil rights, like voting, serving on a jury and owning a firearm, and dispels many of the burdens a misdemeanor or felony marijuana conviction brings.

May Tiwamangkala, a criminal justice organizer for Puente Human Rights Movement, an advocacy organization and member of the Arizona Marijuana Expungement Coalition, was pulled over while on probation in 2015.

Officers reserved the right to search the car, and once they did, found a small amount of marijuana. The charge extended Tiwamangkala’s probation by four years and resulted in additional fines and penalties.

For most, a marijuana charge complicates securing employment, quality housing, financial aid and citizenship.

And marijuana convictions historically hit underserved communities hardest and statistically skew based on race.

Marijuana possession charges historically show up in the top reasons for deportation. And even with full-fledged expungements, charges still hold weight in immigration court and can be weaponized against noncitizens.

Black and Hispanic people prosecuted by the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office face longer sentences for marijuana possession than their white counterparts, a report by the American Civil Liberties Union found.

Tiwamangkala and other advocates expect the same disparities in arrests to carry over into expungements. And through work with Puente, Tiwamangkala hopes to expunge their own record and help others impacted by marijuana criminalization.

Diaz went to one of the first free legal help clinics hosted by National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws and Minorities for Medical Marijuana in April, and when the court started accepting petitions in early July, Diaz was one of the first to send his in.

And the process was relatively straightforward, Diaz said. He filled out his petition form and included with it his name, address, date of birth, email address, name of the law enforcement agency involved in his arrest and his case number.

Then he sent the petition off to the court. And on August 8, 28 business days later, he received an email notifying him of his expungement.

“I was beside myself,” Diaz said. “I had been carrying this thing around with me for 10 years.”

Complications with expungement

Diaz saw a textbook turnaround on his petition, others are not so lucky.

Splintering interpretations of the expungement statute have started to complicate what was intended to be a quick, easy process.

Under the expungement law, people with charges under 2.5 ounces are eligible. But the amount of marijuana in a person’s possession at the time of each arrest is rarely listed on the police report.

This leaves county attorneys and courts to rule on a number of cases where it is not known whether or not a person is truly eligible for expungement.

In Maricopa County, the courts have granted over 3,500 expungements so far and objected to 19. Lawyers and advocates assisting in the expungement process say many did not include the amount on the report, but were approved anyway making the law more lenient.

But in July, Pima County ruled that without the amount listed, or proof the charge did involve less than 2.5 ounces, the court must issue an objection and send the petition to a hearing, making it more difficult to get records expunged.

According to Julie Gunnigle, director of politics at NORML in Arizona and former candidate for Maricopa County attorney, this was a “nightmare ruling,” further complicating a process she believes to be problematic in the first place.

Gunnigle is of the opinion that the expungement process shouldn’t have been a process at all. It instead should’ve been universal and automatic, which she emphasized in her bid for county attorney.

She believes the opt-in system poses unnecessary barriers to a clean slate.

Coalitions + legal help groups

Free legal clinics are trying to bridge the gap. And as they gain more traction across the state, advocates hope to augment access, education and legal help when it comes to the petition process.

It’s free to submit a petition. And under a provision in Proposition 207, the state allocated a $4 million grant later awarded to the Arizona Marijuana Expungement Coalition, a collection of eight legal, advocacy and education groups, to provide free, accessible legal services.

Among the eight is the Post-Conviction Clinic at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at ASU. Students involved in the program typically investigate claims of wrongful convictions, but this year, the focus is on marijuana expungements.

Randal McDonald, supervising attorney for the program, said they plan to help get the word out, assist with expungements and tackle more complicated cases as they arise.

McDonald expects some cases like Gunnigle mentioned — where the amount of marijuana is not listed, or cases where the charge happened decades ago. But some cases, he thinks, may lay beyond the bounds of expectation.

“I anticipate that we will come across some issues that we have never imagined,” McDonald said.

And when the unimaginable comes into play, students will be responsible for communicating with clients, researching their case and appearing in court under Ariz. R. Sup. Ct. 39 to provide pro bono litigation.

“There's a lot of gray area,” McDonald said. “So I think there are going to be a lot of arguable issues where we can step in.”

ASU is part of a larger partnership with other legal and educational programs across the state.

Other members of the coalition include the Arizona Justice Project, D.N.A People’s Legal Services, Southern Arizona Legal Aid, Puente Human Rights Movement, the Arizona American Friends Service Committee, Community Legal Services and the U of A James E. Rogers College of Law Civil Rights Restoration Clinic.

The coalition plans to launch the program in full force on Sept. 1, and the joint hope is to spread the word about expungements and get as many records expunged as possible.

Diaz adopted a similar personal mission.

Since his expungement, Diaz talked to a handful of journalists across TV, radio and print to spread the word about the process and the benefits it can bring.

“Luckily, I heard the message that day, I saw the program,” Diaz said, referring to the segment on the evening news, “It's just kind of one of those things where it's going to take exposure for people to realize.”

Reach the reporter at kiera10riley@gmail.com or follow @kiera_riley on Twitter.

Like The State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter and Instagram.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.

Kiera Riley is a managing editor at State Press Magazine. She also interns at the politics desk for the Arizona Republic