Sunday, Sept. 19, 2021, 3:45 p.m.

Everything I've ever known has been at the discretion of the U.S. government.

It would take 17 and a half years and tens of thousands of dollars before I would finally feel fully integrated into the country I grew up in, basking in the rights and freedoms its citizens enjoy.

Much of what my parents did during those years to attempt to gain citizenship happened behind closed doors; I was far too young to be worried about legal processes.

All I needed to do was tag along to the dozens of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services office visits — a tedious process involving fingerprints, identification photos and doctors offices over the years — while my parents tirelessly dealt with USCIS, raised two kids and worked full time.

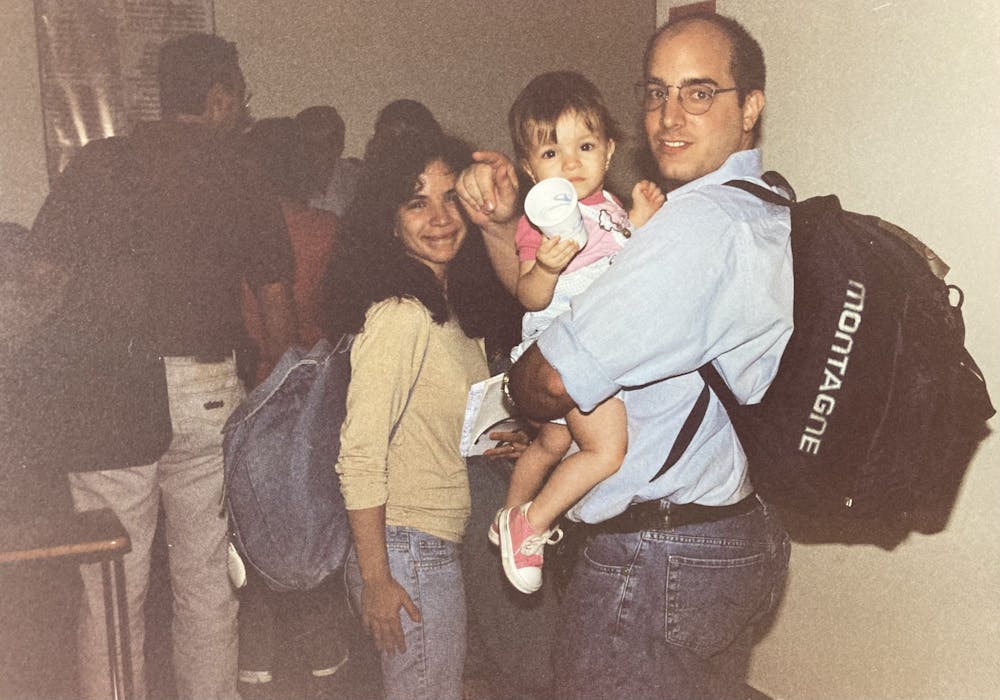

My mom has always impressed me. At 26, she successfully wrote and defended a doctoral thesis in organic chemistry while pregnant with her first child — I was born weeks before her graduation. She moved her young family across the world only a year later and built a life from the ground up.

Tuesday, Jan. 27, 2004, 7:43 p.m.

My family emigrated from Argentina to the U.S. in order for my mom to participate in a fellowship in Washington, D.C. at the National Institutes of Health after she received her doctorate.

My parents and I were escorted to the airport that morning by our entourage — my grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Despite support from our family, it served as a reminder that we would be embarking on this journey on our own.

In order to enter the U.S. for her fellowship, my mom had to obtain a J-1 visa. The visa allowed her to remain in the country for the duration of her fellowship, so long as she proved she was advancing in her career.

The J-1 visa is one of the two most common visas used by international students at ASU. The other, F-1, is meant strictly for full-time enrollment in U.S. academic programs.

Despite the issuance of more than 750,000 F-1 and J-1 visas annually, international students face hurdles throughout their time in the U.S.

According to ASU law professor Evelyn Cruz, international students cannot enroll in a University program while visiting on a B-1 or B-2 visa. They must be approved for a specific status change from a visitor visa to a student visa prior to enrolling.

Eventually, all visas expire and petitioners need to either renew theirs or find a new one.

At the end of their program, J-1 recipients must return to their country for at least two years in order to bring skills back to the countries they hail from. However, my mom learned a way to avoid this contingency: receiving a No Objection Statement from Argentina.

The No Objection Statement waives the return policy, essentially allowing the applicant to stay in the U.S. because their skills are not needed in their country of origin.

But either way, my mom couldn't keep her J-1 after finishing the fellowship, so she needed to find another that would allow her to work and live in the U.S.

She decided to apply for an O-1 visa, meant for individuals with extraordinary ability, a hefty feat for an organic chemistry researcher with less than 10 years in the field.

There are two options for proving exceptional ability in science.

One is receiving a Nobel Prize.

My mom obviously doesn't have a Nobel Prize, so she had to use the second option: presenting a significant amount of published material in scientific journals along with letters of recommendation from professors and peers proving she is among the top in her field.

After receiving 10 letters of recommendation, most from scientists she barely knew, her work was deemed worthy of a Nobel Prize-adjacent visa by USCIS.

Thursday, Feb. 5, 2015, 3:45 p.m.

Eleven years after arriving in the U.S. marked the beginning of stability for my family. We were granted our green cards, ensuring we would be allowed to live, work and study freely in the U.S. for at least 10 years.

I have never seen my dad as excited as the moment when he opened the three letters from USCIS and read our permanent residency application approval.

The process of applying for and receiving a green card is incredibly frustrating. My parents like to say if the person approving applications woke up on the wrong side of the bed that morning, an application would get denied.

My mom applied for a second preference immigrant worker green card, almost the same as an O-1 visa, three times before being approved. She claims the only reasons behind her final approval were corporate connections and dumb luck.

The vast majority of worker green cards require employer sponsorship, meaning an employer must submit the application on the employee's behalf and prove this employee is more qualified than any American to do their job.

The first company my mom worked for after the fellowship wasn't too enthusiastic to sponsor her green card. With her O-1 visa, she had to stay with that specific company unless USCIS approved an employer change, but with a green card, she could freely work anywhere.

They agreed to sponsor her, but the application was denied. Typically, employers will appeal a denial, but my mom never heard any information about an appeal from the company's lawyer.

She applied using the exact materials that granted her the O-1 visa, so she hired a private immigration lawyer to find out what happened and advise her on how to proceed.

It turns out, the company never filed the proper appeal paperwork and let her application fall through. The lawyer said this was a common tactic for companies to retain employees who cannot switch jobs, like my mom. She was now stuck with a visa and had to restart her green card application from square one.

On her lawyer's advice, she requested a switch from her O-1 visa to an H-1B, a skilled worker visa which doesn't tie an employee to a company, and quit as soon as possible. This was her second attempt at an H-1B visa, as she tried to obtain one after the J-1, but was unable to.

The H-1B visa has a cap of 65,000 issuances per year, which are currently given out in a yearly lottery system. My mom believes the system was set up to favor applicants who had access to lawyers who charge thousands of dollars per hour for their services.

Her next employer was far more cooperative with the sponsorship process, since her visa status already allowed her to switch employers. However, because they were a very small company, they didn't have the adequate connections to secure her a green card.

In a stroke of luck, the small company was acquired by a massive science corporation, instantly granting my mom access to some of the best immigration lawyers in the U.S. and securing her coveted title of "permanent resident."

Throughout my mom's various struggles with visa and green card applications and statuses, my dad and I's statuses altered accordingly. The three visas and one green card my mom obtained each had corresponding family visas, so my dad and I never had to figure out which category we would fall under.

Unfortunately, the family visa corresponding to the O-1 visa does not permit employment, so my dad was not able to work while we held that status. This means immigrant families can only have one extraordinary breadwinner.

Sunday, Sept. 19, 2021, 3:45 p.m.

After five years of living in the U.S. as permanent residents, my parents were eligible to apply for citizenship in February 2020. At this point, I was still 17, ineligible to apply for citizenship on my own, and forced to wait. Either I would turn 18 and apply or my parents would get their citizenship first, which automatically grants citizenship to their children.

Of course, the latter would soon prove impossible, and I filed in January 2021.

Ironically, my process moved much faster than my parents', and I received my citizenship Oct. 4, while they have yet to receive their appointment notice letter. They've been waiting a year and a half.

The applications my family filled out and lawyers we used cost about $35,000, most of which my family didn't have to pay for — most of the fees were covered by my mom's employers.

The steep cost is a severe financial barrier for low-income immigrants, many of whom are people of color. Restricting access to citizenship in turn restricts access to citizen rights for millions of immigrants.

The financial obstacle of naturalization blocks large groups of immigrants from voting and helping family members legally immigrate to the U.S. The majority of noncitizen immigrants are people of color, demonstrating systemic disenfranchisement and limiting pathways to legal immigration and citizenship for the family members of those potentially eligible for naturalization.

Armando, a senior studying psychology who asked his last name be omitted due to privacy concerns, immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico when he was seven.

"(Becoming a citizen is) something that I wanted to do before, but it's a lot of money," Armando said, "I just want(ed) to concentrate on paying for my tuition and college."

Despite financial struggles, Armando's father helped pay for a service in Yuma County called Montes Multiple Services that would file Armando's citizenship application and handle everything on his behalf.

According to Armando, the company is very popular in his community. Their immigration services span from helping with USCIS forms to providing an interpreter in a community where over half of the population speaks a language other than English at home.

A significant portion of the U.S. citizenship test requires the test taker to speak, write and read in English, despite the country lacking an official language. This is yet another problematic barrier to receiving rights reserved for citizens, raising the question: Who does the U.S. actually want as its citizens?

I'm aware my situation is highly uncommon, and I'm privileged to have parents with good connections who assisted in granting my citizenship in a mere 17 and a half years. I feel extremely grateful for the relative ease with which my application went through.

I'm thankful I wasn't cognizant enough to understand what was going on while I was a child. I now have a deeper respect for those who navigate the process as adults, especially those whose first language is not English and are experiencing financial struggles.

As this process comes to an end, I've taken time to reflect on the consulate trips, medical exams and excruciating waiting periods that defined much of my childhood.

Each person's process to obtain citizenship is just like the fingerprints frequently provided to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services — completely unique.

Reach the reporter at cpedrosa@asu.edu and follow @_camila_aldana_ on Twitter.

Like The State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.

Camila Pedrosa is the Editor-in-Chief for The State Press Magazine. This is her fifth semester working with the magazine, and she has previously written for Cronkite News, The Arizona Republic and The Copper Courier.