The world was no bigger than the cul-de-sac I lived in until I went to elementary school in Mesa.

Before my eighth birthday, the economy collapsed in the housing crisis of 2008. I didn't know it at the time, of course, but my mom was lucky to have moved to Mesa just before the crash.

I knew from an early age that I was different because I was one of only a handful of Hispanic kids at my school.

I wanted to be like the white kids. I looked for anything we had in common.

My family was just one of many Hispanic families in Mesa at that time. According to the 2010 Census, Mesa's population was 26.4% Hispanic and 2.5% Native American.

I thought I was Mormon because everyone else at school was. When my classmates talked about a boy scout meeting they had the night before, I imagined myself among them.

I started noticing the little things that other kids did, like pronouncing “tortilla” incorrectly or calling their grandma “grandma” instead of abuelita. They went to birthday parties where there wasn't a pinata.

As for the few other kids who looked like me, I oftentimes would find myself annoyed to hear them say words in Spanish like “Tia” or “Tio” because I thought they were trying too hard to let other people know they were Hispanic. It just felt like they were performing for the white kids. I was only 6 and I was made to see my heritage like a performance.

They’d always ask, "what does that mean?" which would lead the other kid to say, "Oh you don't call your aunt 'tia'?" Obviously, a white person wouldn't call their aunt "tia." It felt like they were just trying to show how different they were.

But one time, a new girl started at my school. She was in my grade, but she didn't speak much English. The teacher thought it was a good idea to pair her up with someone who spoke Spanish.

The teacher asked the class if anyone speaks Spanish and would be comfortable talking to her in Spanish. Some white kids raised their hands, and something clicked.

I sat there thinking: "What the hell do they think they're doing? I'm Mexican! And my Spanish isn't even that good, but there is no way these kids from Mesa that don't even pronounce "tortilla" properly can speak Spanish.”

So I raised my hand. Maybe my teacher was thinking the same thing as me, or maybe it was my enthusiasm that lead her to pick me. From then on, teachers would ask me to explain things to her in Spanish and I felt so cool.

I remember one of the Hispanic boys in my grade speaking Spanish to me. It was during recess when we were playing kickball. He told me that he didn't like the kid that was pitching and I laughed.

I had a sudden realization that we could communicate in Spanish and no one would know what we were saying.

I felt like I was part of my own little club. I didn't need to have things in common with the white kids because I had things in common with other kids.

I'm so glad my attitude changed and that I started noticing those things that made me and my peers different, because now I embrace those differences. Diversity is what makes humans so remarkable and I love being able to bring diversity to a room — whether it be because I’m Hispanic or because I live in a different tax bracket than other people.

Going to Costco and getting "only the essentials" was normal in my family. Only recently did my mom officially become middle class.

In high school, going to gated communities and having to ask my friends for the gate code was something I had never experienced. The first time I had to put in a gate code I panicked trying to find the code in my phone because I forgot I needed it.

Even into my teenage years, the differences that I noticed in elementary school took a different shape. There were kids getting cars for their birthday when I still called the car my mom bought 4 years ago "new."

Being grateful was its own hand-me-down. I would think of my grandpa who had to take the first job he was offered when he came to the U.S. He never took a day off. Because of that, I'm able to go to college and have my writing published. I also have an internship that will hopefully lead to a job in the future.

Mom and Pop

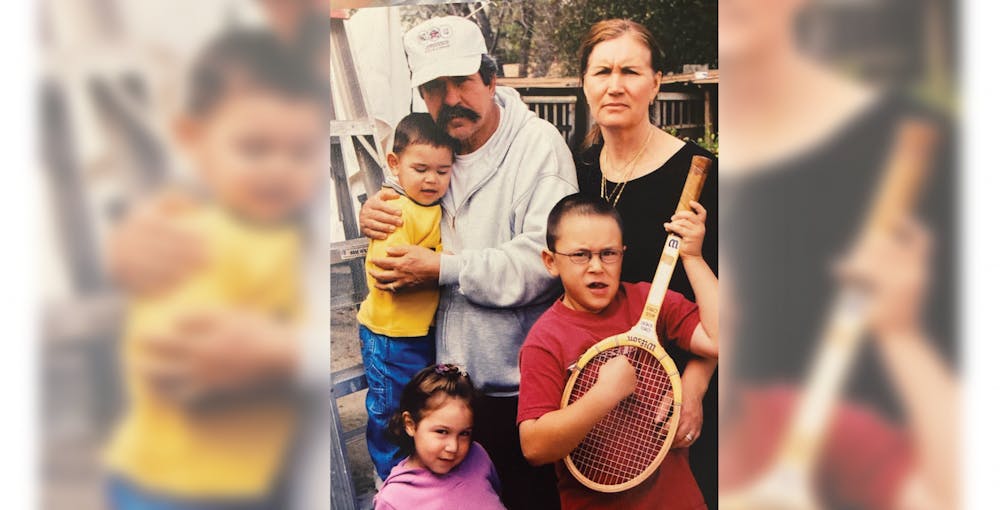

I love being able to live out the reason my grandparents came to the U.S., but my story would be incomplete without talking about my parents.

I think one of life's greatest pleasures is learning about a person; where they grew up, how they grew up, where they went to school, what they were like and how they've changed. I try and reconstruct my own cul-de-sac with their memories.

For that reason, I'm very fortunate to have the parents I have, because whenever they tell me a story from their childhood or from when they were in college, I feel like they're giving me a little slice of their life.

It makes me feel proud not only because of what they've both been through, but because the more I know about their lives the easier it is to tell their story.

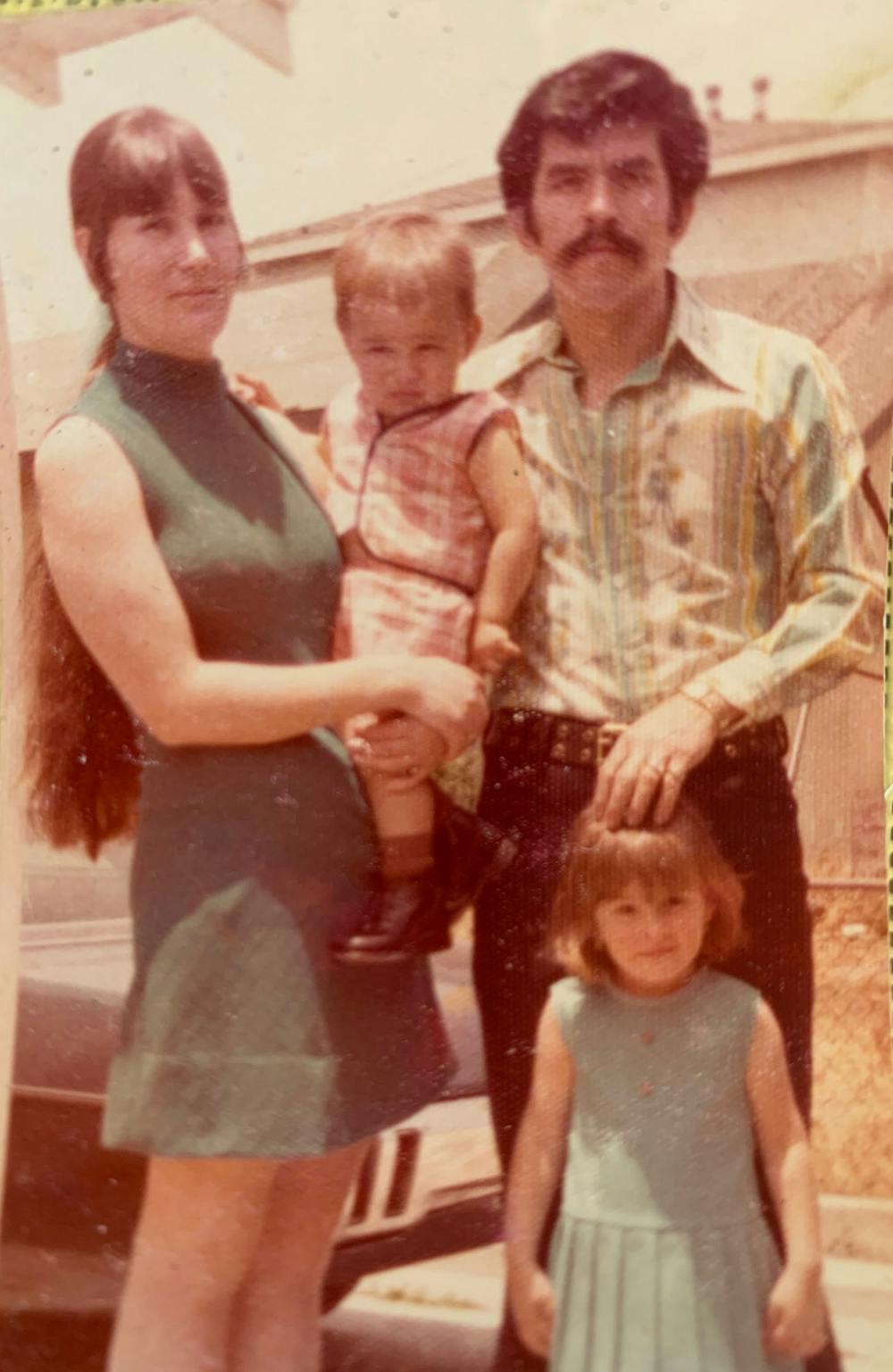

My mom, for example, emigrated from Guatemala with my grandparents when she was only four years old. Getting here was easy for my family, but staying here was a different story. My grandfather was in the Guatemalan military and a drum and trumpet player, but when he came to the U.S., he found work as a garbage man in San Francisco.

This was all happening during a big shift in U.S. immigration where people from Latin America were parting with their home countries.

In 1960, U.S. immigration was dominated by people from Europe and Canada who accounted for 84% of immigrants. By 1970 that number dropped to 68% and dropped again to 42% in 1980.

My grandparents were part of a surge of Latin American immigration to the U.S. in hopes of giving my parents opportunities that wouldn't otherwise be available to them in Guatemala or Mexico.

My parents were lucky enough to be first-generation college students, but they both had to drop out when my mom became pregnant with my older brother. They both eventually went back to school and completed their degrees. It was really special for both of them.

My mom was able to graduate summa cum laude with a 3.97 GPA. My tia was so proud she cried. Suddenly all the sacrifices my grandparents made were worth it because my mom was a college graduate.

She could get a job at a time when the unemployment rate ballooned from 5% at the end of 2007 to 10% in 2008 thanks to the housing crisis. She could make money to support her three children. She could break the cycle of poverty in her family.

My dad was able to start his own business thanks to the sacrifices of his parents. He went from a food truck to a restaurant that had a location in Glendale before he was forced to close shop due to the pandemic.

Family Legacy

My parents are who I want to be.

I want to be able to take advantage of the opportunities presented to me by my grandparents. I want to be able to make them proud and continue their legacy.

People assume that I'm a first-generation college student and I feel like that is almost insulting to my parents.

My situation can almost be a double-edged sword sometimes, especially when I mention that my parents had to drop out of college. They were able to go back to school and find success beyond that.

They inspire me everyday to not only do what they did, but to do it better, all while acknowledging my grandparents who made it all possible.

I'm going to college and getting an education. I’m working two jobs. I’m telling their story.

Reach the reporter at ajgamiz@asu.edu and follow @systemupgraidan on Twitter.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter.

Aidan Gamiz is the Spanish translator for the State Press Magazine. He was born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona in a bilingual household where he learned both English and Spanish.