Across multiple events last week, ASU's Institute of Human Origins celebrated the 50th anniversary of the fossil skeleton "Lucy" – the most complete preservation of one of our earliest human ancestors.

Discovered in 1974 by Tom Gray and Donald Johanson, the founding director of the Institute of Human Origins, Lucy was the most complete fossil of her species, Australopithecus afarensis. Her discovery energized new questions about how early humans moved, ate and evolved, especially proof that they walked on two legs.

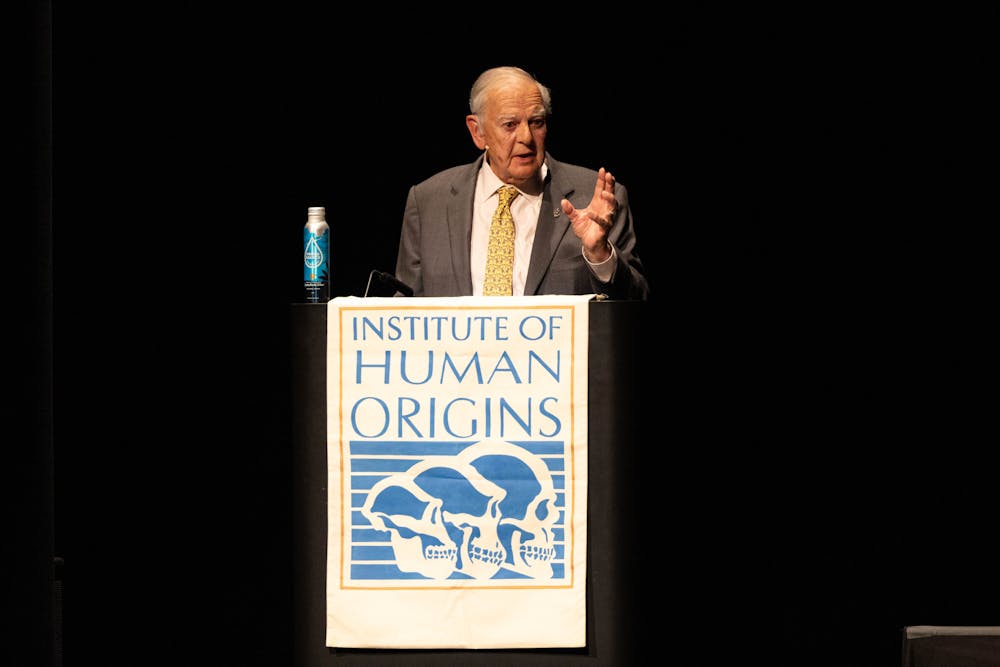

Johanson, now 80 years old, recalled the details of uncovering Lucy in Hadar, Ethiopia, at a lecture held at the Mesa Arts Center on April 4.

"If I had looked to my left, I would have missed the first fragments of the skeleton," Johanson said. "Fortunately, I looked to my right and recognized the little piece of arm bone, and that changed my life (and) changed the trajectory of a lot of research in paleoanthropology."

Lucy quickly became a paleo-celebrity to scientists and nonscientists alike, recently landing on the front cover of this year's Science issue. NASA even named a space probe after her. According to Johanson, Lucy is also a cultural sensation in her country of discovery.

"There's a Lucy bakery in Addis Ababa, there's a Lucy insurance company, there's a Lucy taxi service, (and) the national women's soccer team is called Lucy," he said. "She is known in Ethiopia both as Lucy and as Dinkinesh, as this very wonderful fossil, and is for many people the best-known fossil discovery in our human family tree."

The 3.2 million-year-old skeleton's head-turning appearance on the anthropological scene spurred further discoveries. Experts worldwide gathered at the Rob and Melani Walton Center For Planetary Health on April 6 for a symposium hosted by IHO to commemorate Lucy's impact on the field.

Ian Tattersall, the curator emeritus of the American Museum of Natural History, explained that Lucy was a tipping point in paleoanthropology that refuted the previous, oversimplifying theory that human evolution improved linearly.

"After Lucy had come onto the scene, demanding to be fitted into the larger picture, everything would change," Tattersall said. "The extra taxonomic space that Lucy created eventually allowed a much more dynamic, and actually, a much more nuanced picture of human evolution to unfold."

Zeray Alemseged, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Chicago and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences who started at IHO, discussed how Lucy's discovery led his team to uncover the fossilized Dikika Child. This discovery is also known as "Lucy's baby," despite the fossil being 100,000 years older than Lucy.

"She serves as the benchmark for subsequent discoveries," Alemseged said. "Hence larger than Lucy, smaller than Lucy, etc. She was a big inspiration for more fieldwork. I was inspired in many ways because of the discovery of Lucy."

Alemseged showed photos of him presenting Lucy's fragments to former president Barack Obama and Pope Francis to illustrate how she is also "an inspiration for institutional development."

Carol Ward, a curator's professor at the University of Missouri who co-leads the West Turkana Paleo Project, said that technological reconstructions of Lucy's skeleton show that she walked on two legs but retained some ape-like features like the shape of her rib cage.

"That suggests maybe even stronger climbing adaptations were retained," Ward said. "(But) she would have been capable of basically very effective and very efficient bipedal locomotion."

Ward also noted that apes had a longer digestive tract than humans, which meant they could thoroughly process the nutrients in vegetation.

"To go from something like Lucy to something like us would have involved shrinking the size of the digestive tract," Ward said. She said this points to a connection between a change in locomotion and a change in diet.

"Lucy not only taught us things about these early ancestors, Lucy taught us new ways to think about early human evolution," Ward said. "In science, to get the right answers, you have to ask the right questions. Lucy gave us new questions which are continuing to be refined; some are better answered, some we're still debating."

Jessica Thompson, an IHO alum who works at Yale University, said we could better understand early humans' diets by examining Lucy's cranial capacity.

"Lucy was doing something dietarily that was very different from what other organisms did," Thompson said. "So the spotlight on Lucy is really about, she could kind of do it all. Lucy and her kind were able to consistently get more power, then expend fewer calories, whatever it was they were doing."

Thompson indicated that this advantage could have been brought about by "clever" tool usage.

Tracy Kivell, a researcher affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said fossilized finger bones revealed what Lucy could accomplish with her hands.

"There's no doubt in my mind, at least, that Lucy was a very capable tool user and tool maker," Kivell said. She said this indicates that various early human ancestors "had sufficient dexterity to use tools" but were still regularly using their hands to move around.

"(Lucy's) discovery ignited novel investigations into what makes the human hand distinct," Kivell said.

The symposium laid out ideas that were only possible following Lucy's discovery in 1974, and it formulated new questions that could help people understand where they came from and how they evolved to the present day.

"I hope we can somewhat enrich our better understanding of where we've come from," Johanson said. "I think it's interesting (that) with the revolution in genetics, we see all of us carry within us primal genes that first evolved in Africa so that we're all united by our past."

Edited by River Graziano, Walker Smith and Grace Copperthite.

Reach the reporter at mosmonbe@asu.edu and follow @miaosmonbekov on X.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on X.

Mia Osmonbekov is a senior reporter. She previously reported for Arizona Capitol Times, Cronkite News DC, La Voz del Interior and PolitiFact. She is in her 7th semester with The State Press working previously as the opinion editor and assignment editor.