Listen to the article:

When I was five years old, Sarah Paulson shoved me. When I was eight years old, Owen Wilson threw me off a roof. When I was ten years old, I faded into obscurity.

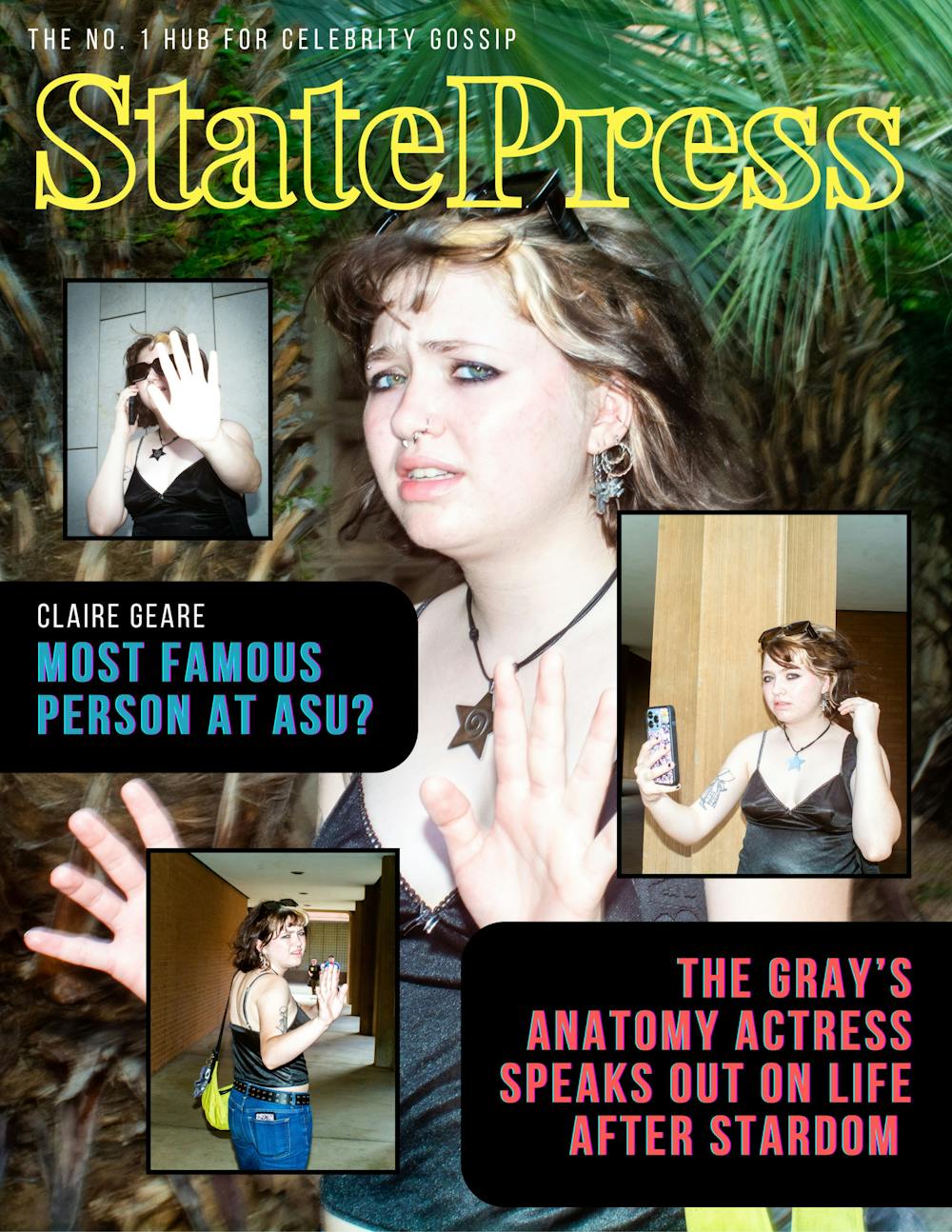

I have a confession to make. I, Claire Geare, was a child actress. Not community theater, not local commercials, not school plays — I appeared in front of millions of people. It’s strange to say that now. I go to ASU. I work in a cafe. I barely make enough to cover rent each month, just like every other person on this planet. But for a few years I barely remember, I lived like a star. Billboards across Hollywood had my face on them, national commercials ran with me in them, I worked alongside real celebrities. From ages three to nine, I was the shit.

One of my very first memories is spitting fish sticks out into a cup held by a man twenty times my size. The commercial was for Mrs. Paul’s, a frozen fish company. I remember the line clear as day — “Minced? You feed me minced? You ever catch a minced fish?” I was meant to play a precocious little girl, too smart for her own good. I remember feeling like an asshole. Even 3-year-old me knew not to talk to my mother like that.

Years later, a curious boyfriend of mine decided to find the commercial on YouTube. Underneath were about a dozen threats of child abuse. It’s not that I care, it’s just — strange. I was being picked apart 15 years ago by strangers on the internet. Told I should starve, that I’m not funny, that I should be physically hurt over a fish stick commercial — you know, typical things you say about a 3-year-old on the internet.

The comments aren’t all bad. In truth, most of them are good. People thought I was cute, or funny, or interesting, or something other than deserving of a good smack across the face. But that feels strange, too. It all feels strange. No matter if I’m loved or hated, there’s just something weird about being perceived at that age. Most 3-year-olds get to live life pretty much anonymously, being known only by their family and daycare. I was known nationally.

The illusion of choice

To achieve this national notoriety, acting wasn’t just a part of my life, it was my life. I’d wake up in the morning and be handed a script by my parents, explaining that the audition was the next day. From the morning until night time I’d learn and recite my lines. I remember pacing around the kitchen island, whispering words to myself that I hardly knew the meaning of. Practicing my delivery, nailing my body language, getting into character. I couldn’t have been older than six.

Do you ever think about those family vloggers? You know, the ones constantly shoving a camera in their kid's face — documenting every toothache, bad grade and meltdown as the poor child learns to better recognize a camera lens than their mother’s facial features. Well, I think about them. I think about them a lot. Maybe it’s out of sympathy, or maybe it’s out of disgust, or maybe — just maybe — it’s because I know what it’s like to be that little kid.

Most kids remember being pushed on the swing by their parents, doing the day's math homework or going to the neighbor’s house for dinner. The most time I ever spent with my father was on the way to auditions. That’s not to say these memories aren’t happy ones, for a good deal of time they were. But still, my quality time with my family was work.

There’s something really beautiful about being born. I mean, besides all that mushy miracle of life shit. Because for a brief moment, maybe for the one and only time in your life, you’re blessed with the gift of anonymity. You’re just a baby in a hospital, unknown to the rest of the world. But maybe I say this and it isn’t true anymore. There are tons of parents who post on Facebook moments after giving birth, ending my utopian dream of privacy at the click of a button. Or there are celebrity babies who never had a chance. But when I was born, way back in 2004, I was nobody for a while.

That didn’t last long.

It’s hard to have a projected image of yourself for all to see. These days we do it voluntarily, building a brand for ourselves in an increasingly pervasive digital space. Not to sound like an old geezer, but creating an imaginary version of yourself can’t be healthy. Yet, this is a choice we make. Sure, it doesn’t feel like a choice — it seems that sometimes you may as well be a hermit if you don’t have an Instagram — but it’s a choice all the same. We could all choose to denounce our made-up versions of ourselves, delete our Instagrams and Facebooks and LinkedIns at the drop of a hat. Yet for me, this imaginary version of myself is what kept the lights on.

The point is, it sucks to be known. It hurts. It hurts to have a public image from as far back as that age, and sometimes I feel like it hurts to have one at this age, too.

Life on film

My parents used to say I was a “method actor.” I’m not exactly sure what that means at that age. They used to tell me that if I wasn’t careful, I’d end up like Heath Ledger. I don’t know why you’d tell your 8-year-old that because what “method” really entailed was post-traumatic stress disorder.

One of the last projects I ever worked on was a film about a coup taking place in a foreign country. I remember endless blood, gunshots, rape and violence. It’s hard for kids to separate what’s real from what’s imaginary at that age. It’s why parents don’t let them watch scary movies. But my life was a scary movie.

I saw the blood. I heard the gunshots. I remember the violence. Sure, I knew it was fake blood, fake violence and unloaded guns — but try telling my brain that. When all you see every day is horror, how is it not supposed to impact your development?

There was also a sense of degradation in my career. In one movie, my character pees her pants. In others, I was forced to play dumb. I felt so ashamed. I was at the whim of writers, directors and producers constantly telling me what to do and how to act. Once again, the freedom of choice was ripped away.

There are many ethical questions surrounding child stars — too many to get into here. Should a kid that age even have a career? Should they be exposed to adult content? Should their money be used to support a family? The truth is, I don’t know. You’d think I’d have stronger opinions, being that I’ve been through it, but truthfully I couldn’t tell you what the right thing to do is.

There are many aspects of my former life that I deeply regret. I don’t know if regret is the right word. Can you regret something you had no control over? Yet, the feeling reeks of it.

I missed my childhood. I had no friends besides my brothers and sister. Instead of school, I was tutored on set. I was constantly working. An endless slew of commercials, TV shows and movies demanded my full attention. What kind of childhood is a career?

Even despite the trauma, the degradation, the constant self-awareness, I wouldn’t change it for the world. I spent my formative years doing the things kids dream of. I had purpose. I’ve always liked to succeed and success is what I found. I met wonderful people through my job, people I’ll never forget.

There was a woman on my last film I lovingly called “Fluffy Nat.” She had a ridiculous job, providing me hand warmers in the cold and holding umbrellas over my head in the heat. I was essentially given an assistant at the ripe age of 8 — but she quickly became my closest friend on set. We didn’t speak the same language, but she was my greatest supporter.

There was also a man whose name I can’t remember on the set of another film. He used to grab hot wax out of candles for me and my sister to play with, just because he knew we liked it. Where else do you meet a man who will stick his hand in a burning candle for you? These grown adults were my friends, filling in for school-aged children and teachers. They taught me everything I know.

I stopped acting when I was 10 years old. That wasn’t my choice either. My parents got divorced, their marriage held together by the thread of my career. We moved to Arizona. I finally went to school. The phone stopped ringing.

From “was” to “wannabe”

When I was 14 years old I made my first choice. I joined the school newspaper and the literary magazine, which began my second career: a writer. As much as it feels strange to be picked apart for something you had no input in, it feels even stranger to be picked apart for something you did. I began to get published, my writing out there for the whole world to see. It’s such a personal thing — it’s your thoughts, feelings, opinions, all recorded on a page. This work is still out there today, online on my school newspaper’s website, written in an award-winning magazine. God, how embarrassing that is.

I’ve learned throughout the years that 14-year-olds really shouldn’t have a platform. I had trash opinions and shit satires. Half-baked reports and poor movie reviews. Out-of-rhythm poetry and narrative pieces clearly written by a child. If you can write it, I’ve published it. And truthfully, I have many regrets. This time regret is the right word. For the first time in my life, I was autonomous. I chose to publish what I did — and looking back, I was an angry, confused little girl.

I wrote a satire every month for my school newspaper, and when I did, it was mostly about how much I hated my classmates. I used to think it was biting commentary, but in reality, it was just pure vitriol on a page.

I recently went back and read some of my articles and, oh boy, I wish someone had told me how hateful I truly was. I wish I could apologize to everyone in my high school. Nowadays, I still write satire for this very publication, and it’s gotten me into trouble before. When I was a freshman, I wrote an article absolutely trashing an organization I’m a part of. Surprisingly, they didn’t like that very much. I didn’t like myself for that very much, either.

The point is, I made a choice. And as much as I feel regret over the lack of choices I had as a child, I regret the choices I did make as a young adult even more. It’s scary to have autonomy. It’s even scarier to exercise that autonomy publicly.

I have a podcast. I’m an improv performer. I’m a comedian. I’m a writer. I chose to put myself back out there, and as with every choice you make, there’s bound to be some regret. I sometimes wonder what a life in anonymity would look like for me. I could stop pursuing my dreams in entertainment, get a marketing degree and settle down in Arizona. I could get married, start a family and forget about my past. But I don’t want that, and I’m not sure why. Maybe it’s because I feel I have something important to say, maybe it’s just because I was born this way or maybe it’s just a desperate need for attention. No matter what it is, here I am.

And as with my child acting career, I wouldn’t change my writing career for the world, either. I’ve made many mistakes, but I’ve also published some truly beautiful pieces. I’ve learned a lot, I’ve grown a lot and I’m not such a hateful little girl anymore.

I’m a human being with a purpose. I’ve written about my autism, my experience with the school’s disability services, my queer experience. I’ve also written dozens of satires — some of them really fucking funny.

All this brings me to the here and now. I’m just a girl with a German Wikipedia page and a Twitter account impersonating me. A girl with many regrets. A girl who keeps putting herself out there despite the hurt. Despite the shame. Despite the mistakes. I am just a girl in the public eye, and that is a choice I’ve made.

Edited by Savannah Dagupion, Leah Mesquita and Audrey Eagerton.

This story is part of The Active Issue, which was released on October 4, 2024. See the entire publication here.

Reach the reporter at cageare@asu.edu and follow @notevilclaire on X.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook, follow @statepressmag on X and Instagram and read our releases on Issuu.