In early September, the U.S. Department of Education terminated 25 grants related to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act after a review decided the funding did not align with the administration's priorities and executive orders, according to the Council of Exceptional Children.

The Department of Education cited a grant may be terminated "if an award no longer effectuates the program goals or agency priorities," according to the executive order. The order also stated a study showing more than one quarter of new National Science Foundation grants were given to diversity, equity and inclusion and "other far-left initiatives."

Teacher trainings, university programs and parent resource centers are at risk, according to Education Week.

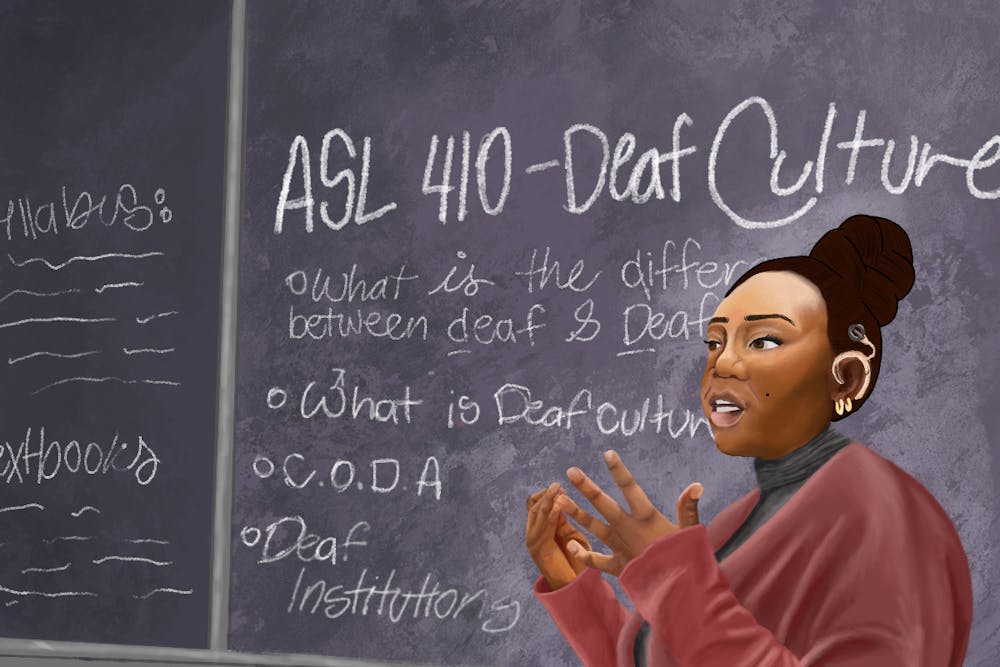

While ASU currently does not offer any degree, minor or certificate programs in American Sign Language or any deaf-related field, the school does offer a few courses. Some faculty at ASU are fighting to increase visibility for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community on campus.

ASL teaching assistant professor and ASL coordinator in the School of International Letters and Cultures Hannah Cheloha has been spearheading the development of an ASL minor for the past three years.

Cheloha has seen many students express interest in learning sign language because of its real word applications.

"The minor in ASL is an interdisciplinary program designed to provide students with foundational ASL proficiency, cultural competency, and professional applications for careers in a wide array of fields," Cheloha said in a written statement.

The goal of the minor would be to ensure students are prepared for inclusive, community-embedded and socially responsible careers in the discipline they choose to pursue, Cheloha wrote.

In Arizona there are about 25,000 culturally Deaf people, according to the Arizona Commission for the Deaf and the Hard of Hearing.

"We want to make sure that, that child, whether they're deaf, hard of hearing (or) deafblind, that they have immediate access to language," Michele Michaels, the hearing healthcare program manager at ACDHH, said. "We don't want any kind of language deprivation (or) delay in acquiring language."

Meeting the needs for every person in the Deaf and hard of hearing communities can look different for everyone.

"There's a spectrum of deaf and hard of hearing people and deafblind people," said Nikki Soukup, the interim executive director for the ACDHH. "Not one size fits all, but ASL is definitely essential."

Alicia Abeyta, a freshman studying psychology, said ASL is one of those languages that people do not often think about or appreciate because it's not a spoken language.

Abeyta is currently enrolled in an ASL course where she reviews vocabulary and practices with partners in class. The course teaches numbers and colors, along with how to form full sentences with proper grammar.

"It's easier if you're talking to someone who's deaf and you're not just writing to each other, and you're actually taking the time to learn their language," Abeyta said.

This type of community building and communication is what Cheloha is aiming to achieve with creating the minor in ASL at ASU.

ASL teaches students "about other people that aren't like them. It helps them become compassionate and it helps them with their thinking in a way that is different," Cheloha said.

As a visual language, ASL changes the way your brain works compared to spoken languages that do not draw on as many skills, she said.

ASU may not currently provide ASL interpreter certification but taking a course opens the door for students to view being an interpreter as a potential profession.

"A lot of people don't realize that ASL interpreting is a career," Soukup said . "We are actively looking to grow the interpreter profession here in Arizona."

In her 25 years working as an interpreter, the most common thing Cheloha noticed among deaf individuals is the desire for more people to learn sign language.

Cheloha said many deaf people in academics have a wider opportunity to communicate with others including their students, colleagues etc. who "often can sign." However, for deaf individuals in general, "there's a lot of loneliness," she said.

"That's been really a driving force of trying to open up the world for deaf people so they can have more fulfilling (interactions) with people and opportunities for work," Cheloha said.

Edited by Natalia Rodriguez, Senna James, Tiya Talwar and Ellis Preston.

Reach the reporter at galawre3@asu.edu.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on X.

Grace Lawrence is a reporter for the community culture desk at The Arizona State Press. This is her 1st semester working with The State Press.