Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect the number of open investigations into alleged sexual harassment under ACD 401.

Over the past several months, nearly every institution in the U.S. has been forced to reckon with the prevalence and ramifications of sexual harassment — ASU included. We took a look at ASU's role in academia's #MeToo movement, what options exist for reporting sexual harassment within and outside of ASU and what the University is doing to stop harassment.

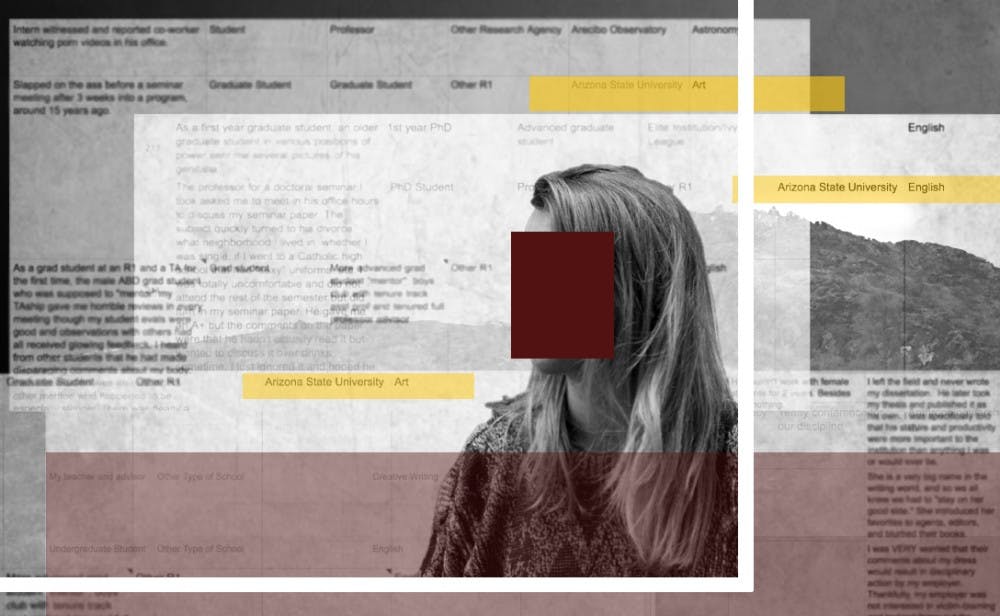

Academia’s #MeToo movement

When Karen Kelsky, a former anthropology professor and the founder and president of The Professor Is In, published a survey asking victims of sexual harassment in higher education to anonymously share their stories, she said she did so knowing that people were “desperate” to have a conversation about sexual harassment in academia.

The survey, which is still open for submissions, has generated nearly 2,400 responses, nine of which pertain to ASU. Kelsky said that the stories shared through the form are “catastrophically bad.”

The nine responses that identify ASU involve disciplines that range from English to art to marketing. The incidents reported in the survey include alleged inappropriate comments, unwanted touching and sexual relationships marked by unequal power dynamics. Survey respondents expressed fear of retaliation, frustration over a lack of consequences for alleged perpetrators and negative career and mental health consequences.

“My goal was not to launch grievances against particular individuals,” Kelsky said. “My goal was to remove plausible deniability from institutions.”

According to an ASU spokesperson as of Feb. 12, ASU has 25 open investigations into alleged sexual harassment, as defined in Section 401 of the Academic Affairs Manual.

What is sexual harassment?

ASU defines sexual harassment as unwelcome behavior of a sexual nature that is made an implicit or explicit condition of education, employment or participation in University activities, or for which the individual’s response to behavior affects their education, employment or life at ASU. According to this definition, sexual harassment includes unwelcome behavior or sexual conduct that is severe or pervasive enough “to create an intimidating, hostile, or offensive environment.”

In her crowdsourced survey, Kelsky refrained from giving a particular definition of sexual harassment, deciding instead to let victims define their own experiences.

“Sexual harassment is debilitating and destructive even when it’s not a rape or assault or stalking, even when it’s a comment like ‘Wow, your legs look great in that skirt,'” she said. “The victim suddenly feels like she’s not a scholar, she’s a sex object.”

Options for reporting sexual harassment at ASU

ASU strongly encourages survivors of sexual violence and harassment to report incidents to the University, according to a written statement. To do so, survivors may choose to file a criminal report with the ASU Police Department or an incident report with the Office of Student Rights and Responsibilities or the Office of Equity and Inclusion. They may also report the incident through the ASU Hotline.

In addition to these formal channels, sexual harassment can be reported to any ASU employee. All ASU employees are mandatory reporters and as such are required to immediately bring the reports to the attention of the Office of Equity and Inclusion and the Title IX coordinator, according to University policy.

Reports can be made anonymously or by a third party, but University policy warns that ASU's response to such reports may be limited due to lack of information and verification.

Harassment investigations are handled by ASU’s Title IX coordinator or by a designee of the chief human resources officer. The investigator is required to reach out to all involved parties, giving them opportunities to tell their stories.

The investigator will also reach out to administrators, such as deans or directors, who can be tasked with ensuring the person who reported the incident doesn’t experience retaliation during or after the investigation. The University may take interim measures such as changing class or work schedules or student housing arrangements.

University policy stipulates that sexual harassment investigations should be completed within 60 days. Once the investigation is completed, the investigator writes a report, which is given to the university provost or the vice president for the division corresponding to the complaint. This administrator has the option to accept, reject or modify the report’s findings. This determination is made according to the standard of preponderance of the evidence, and it is final.

After a determination is made, disciplinary action may be taken, which can include suspension, firing and expulsion.

If an ASU community member wants to discuss his or her experience in a confidential setting, he or she should contact ASU Counseling, ASU Health Services or ASU PD Victim Advocate, which are not under the same mandatory reporting requirements as other University departments.

The ASU Title IX office declined a request for an interview for this story. An ASU spokesperson said the University worries "that if people like (the Title IX coordinator) ... speak in the press, someone who might wish to report an incident could become uncomfortable doing so."

Beyond ASU: Reporting and addressing complaints outside the University system

Those who have experienced sex discrimination in the form of sexual harassment at ASU or other federally funded education institutions can file a complaint online with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR). If they do not want to, complainants aren’t required to go through ASU’s complaint process before filing with OCR. Employees affected by sexual harassment can also file a complaint with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

In addition, a number of professional academic organizations have their own systems for addressing sexual harassment complaints in their disciplines. Many organizations have specific procedures focused on preventing harassment at organization-sponsored events like conferences. Kelsky said that academic conferences can involve particularly high rates of sexual harassment, notably because they reinforce an “incredibly unclear boundary between professional and personal life” that she said already exists in academia.

Cheshire Calhoun, an ASU philosophy professor and the chair of the American Philosophical Association’s board of officers, said it is important for academic organizations to provide support for members who have experienced harassment. In 2015, the association addressed the issue of sexual harassment in an open letter to its members in which it emphasized the importance of education and called upon members to contact the association's ombudsperson if they have been harassed.

Still, professional organizations' ability to investigate and sanction harassment is extremely limited — they can remove someone from an event or censure an institution, but the burden for punishing sexual harassment falls on the universities themselves.

"A professional organization is not positioned to impose any kind of meaningful sanctions in a way that an academic institution can," Calhoun said.

Looking to the future: prevention efforts on campus

ASU has a number of initiatives that seek to prevent sexual violence and to provide resources for when it occurs.

Rachel Kuntz, a philosophy sophomore, is the coalition director for one of those initiatives: the Sun Devil Movement for Violence Prevention. The movement seeks to bring together student organizations to build a campus-wide coalition to educate students about sexual violence.

Kuntz said the coalition includes around 20 student organizations. Some, such as Devils in the Bedroom or the Womyn’s Coalition, are more involved in the sexual violence prevention movement, while others, such as Undergraduate Student Government or the Graduate and Professional Student Association, have broader purposes.

The movement recognizes that sexual violence is a continuum and that all acts of violence — whether they be harassment, assault, catcalling, or others — feed into each other, Kuntz said.

Kuntz also said that while a particular incident may affect an individual, there is a larger ripple effect that acts on the entire campus community.

The movement is currently helping its member organizations plan education events for Sexual Assault Awareness Month, which will take place in April.

ASU also offers the Sun Devil Support Network program. The network trains students to become advocates for ASU community members who have experienced sexual violence.

In a written statement, the University said that prevention efforts are intended to empower students, staff and faculty.

“The number of reports will rise as awareness and trust grow; members of the ASU community are understanding their rights, reporting incidents and seeking support services,” the statement said.

ASU employees are required to undergo sexual harassment training, which covers topics such as how to respond when approached with harassment allegations. Calhoun said she was “very impressed” with the extent of the training.

While prevention efforts are critical in combating the problem, Kelsky said that reducing sexual harassment in academia will require broader, more systemic reform across universities.

“There are just countless layers of enablers,” Kelsky said. “These predators don’t operate in isolation, they’re enabled by an entire infrastructure of people who would rather protect the abusers than support the victims.”

Calhoun said that one of the American Philosophical Association's main strategies for combatting discrimination and harassment is increasing the number of women in philosophy.

“One dimension of sexual harassment has to do with the gender demographics of disciplines,” she said.

Kelsky said that one of the worst reactions to sexual harassment stories, which was seen in the #MeToo movement in the entertainment industry, is the idea that through publishing these stories, “we’re destroying the careers of brilliant men.”

“What I say to that is, for every one man who harasses, there is almost never just one woman,” Kelsky said. “How much scholarship, what cure for cancer do we not have, what solution to climate change do we not have, because so many hundreds and thousands of women have been hounded out of academia entirely or had their research totally compromised by this siege of harassment they are put under?”

If you have reported sexual harassment at ASU and would like to share your story, please contact the reporter.

Reach the reporter at maarmst7@asu.edu or follow @MiaAArmstrong on Twitter.

Like State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.