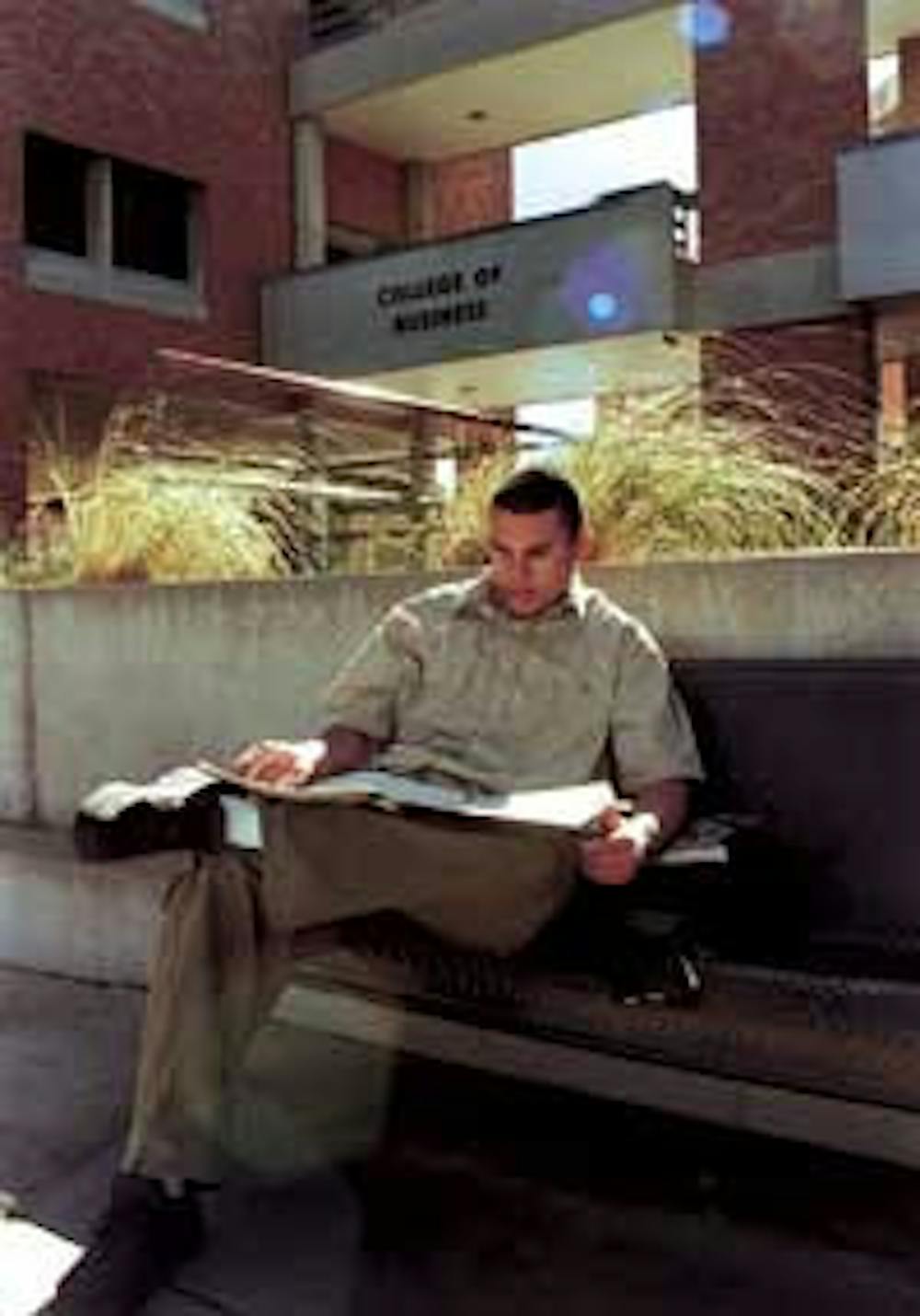

David Sweet hurried through his management school applications early this year as he prepared to return to school. His employer in New York, Studiopolis.com, a once successful new media dot-com company, had folded in November 2000.

Sweet, a first-year Master of Business Administration full-time student at ASU, was a part of the dot-com surge that took place in the late 1990s — in which people working for Internet startups dreamed of making it rich within a couple of years. Students did not want or need to go through graduate-level business schools, as there were plenty of companies with high paying jobs willing to hire young executives under the age of 40.

However, the situation has changed radically over the last year. Students like Sweet are leaving the belly-up dot-coms to further their education in hopes of securing higher-paying jobs.

"During the good times people are paid a ton of money. So attending an expensive business school or any school at that point meant that not only were you losing money in the job market but you were also paying to study," Sweet said. "This phenomenon is what we call 'Opportunity Cost' in business parlance."

However, with the burst of the dot-com bubble in the world of commerce, enrollment in business schools, especially part-time and evening programs, has increased over the last year as students return to school either to escape the recession or enhance their résumés with the coveted three-letter acronym — MBA.

"Hundreds of companies literally disappeared overnight, including my own," Sweet said. "I started looking at the job market and realized that I would need to expand my capabilities to survive longer than the other (average) Joes out there."

Sweet chose to return to school in the belief that during a recession the MBA professionals still get the jobs. "They may not get four job offers or astronomical salaries with stupendous signing bonuses, but everyone still has more chances of getting employed. It always pays to have an MBA. And of course, you are not losing out on the good jobs out there as they are not there anymore."

Economic lows, enrollment highs

The return of business students like Sweet is reflected in the increase in enrollment in management schools around the country. ASU College of Business administrators said enrollment in business schools soars when the economy is bad and drops as it improves.

Larry Penley, dean of the ASU College of Business, said that although students were reluctant to return to school — and leave their lucrative jobs — in 2000, the program has witnessed a 30 percent overall increase in enrollment this past spring.

"I don't think the rise and fall of the dot-com business had a serious effect on our program," Penley said. "It was thought that in spring 2000 we would lose students to the dot-coms, but that did not happen and my guess is that we lost less than 20 percent of our students during that time."

Professors at ASU argue that MBA graduates are the ones who have the best options during a recession period.

Lee R. McPheters, associate dean of the ASU College of Business, pointed out that there are a number of students who are joining the evening and executive programs during this uncertain period in the economy even though the ASU full-time program has seen a drop in enrollment from last year.

"Sure there is a slowdown in the economy right now, but when the recovery comes you don't want to be stuck without talent," McPheters said. "And if you want to earn more, then you have to be worth more and that is the premise with which our students join the program."

However, McPheters' beliefs are not shared by some in the ASU MBA 2001 class. Students who joined the MBA program in 1999 have graduated in the moribund job market of today. Many of them are questioning the worth of their business degrees.

How much is a MBA worth?

Deep Thomas, an ASU MBA 2001 graduate currently working for American Express, contends that the business degree has not helped him in the current job market.

"I had hoped that the MBA would help me earn at least 25 percent more than I am currently but since we graduated with a recession in the market it was a complete reversal of what the market was in 1999," Thomas said. "I had to work hard to simply keep my job."

Others are marginally optimistic.

Suresh Pallamreddy, also a 2001 MBA graduate from ASU now working for a design firm in Phoenix, looks at his degree as one that would probably help him in the long run, but said it is not something that he can use in the current economy.

"When I entered the program, all the jobs were in the technology firms but within a year they had all vanished," Pallamreddy said. "The recession cannot last forever, and it may take people longer now to land the big jobs that seemed possible just a year back, but an MBA is still something that is useful in the long run."

Business schools are adapting to the new situation by restructuring their curriculum to reflect the needs of the new and returning business students.

When the dot-com boom was taking place, the ASU program, along with the rest of the business schools across the country, restructured its curriculum to incorporate highly sought-after courses such as e-commerce and e-business.

Nancy J. Stephens, faculty director of the MBA evening program, said that an e-commerce class was added to the curriculum two years ago to meet the demands of the economy at that point.

With the situation being very different today, are administrators rethinking their strategies for the curriculum? Stephens does not think so.

"I don't think e-commerce was a fad at all. It's as solid as a rock," Stephens said. "That is what the business of tomorrow holds for us. It was the weak companies that crashed during the dot-com debacle, and the companies that survived are here to stay — and so is e-business."

Back to business basics

However, the Dec. 2001 issue of BusinessWeek paints a different picture for the future of e-commerce and management studies, suggesting that students are now choosing to go back to the traditional areas of banking and consulting. Students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have persuaded the administrators to change the title of the school's two-year-old e-business curriculum to Digital Business Strategy because they are worried about the negative impression of an e-commerce specialization in the current job market.

This disillusionment with e-commerce courses, however, is not affecting all areas of management education. Online courses or e-learning is one of the fastest growing segments of business education offered by universities, the online programs cater to the adult population interested in continuing education.

Andy Philippakis, director of the ASU MBA online program, said the 1-year-old program evolved due to collaboration with the John Deere Corp. The company wanted to impart management education to its employees that do not have time to study in the traditional classroom setting, but are still willing to do so on their own time.

Duke University's Fuqua School of Business has been offering MBAs for working executives since 1996 but ASU has developed the first program where executives from corporations are taught in a group and the content is structured specifically for the needs of the organization.

"We are the first university to develop this corporate cohort model and even though the tuition for this program is higher than the other business degrees at ASU, at about $50,000 per student for two years, the university fees overall are lower than most colleges," Philippakis said. "At this time we are not planning on opening this to the general student crowd but want to keep it for upcoming leaders within corporations, primarily the middle managers."

These programs often have about 65 percent of the work delivered online and 35 percent in classes and charge higher fees than the traditional lecture classes in business schools.

Fewer jobs, more students

As the gloomy economic news would suggest, fewer companies are visiting business school campuses to recruit students.

Kitty McGrath, director of the ASU MBA and Graduate Business Career Management Center, said that MBA schools across the country are experiencing a national decline of 25 percent to 40 percent in campus recruiting. But in the dot-com heyday, recruiting was all the rage.

"However, in the year 1999-2000, the ASU MBA saw a dramatic increase of 40 percent in recruiting and I have never seen such an increase in all my 20 years in college recruiting," McGrath said.

This year corporations around the country began rescinding offers, modifying salaries and delaying employment start dates.

"Companies like Hewlett-Packard, who have hired ASU MBAs heavily in the past are not hiring at all now, here or anywhere," McGrath said. "Also, many companies are not offering any signing bonuses as they do not have to. They are assuming that with the economy slowing down, students will not have many companies offering them jobs anyway."

Despite the decline in recruiting, David Sweet feels his MBA is providing him with a set of contacts to network with and an all-around training to be a top manager in the specialization of his choice. His MBA is something he feels will be lucrative in the job market.

"The rigors of studying an MBA makes one more competitive in the marketplace anyway, and is definitely a step up in one's career," Sweet said. "The only stress by the time I graduate is the effort to actually secure work afterwards and pay off all the loans."

That is the goal of MBA students like Sweet — to graduate with less stress and more money.

Reach the reporter at ctitam@hotmail.com.