Katie Connor faces her past every day.

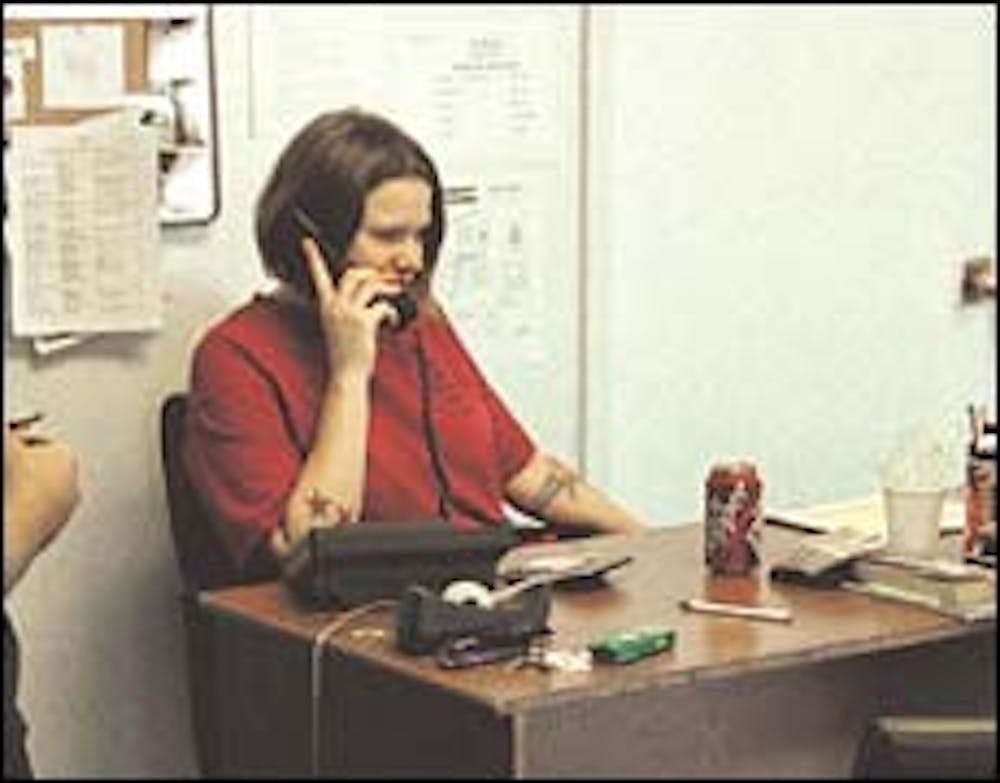

She works at the Tumbleweed Tempe Youth Resource Center as a full-time youth care worker.

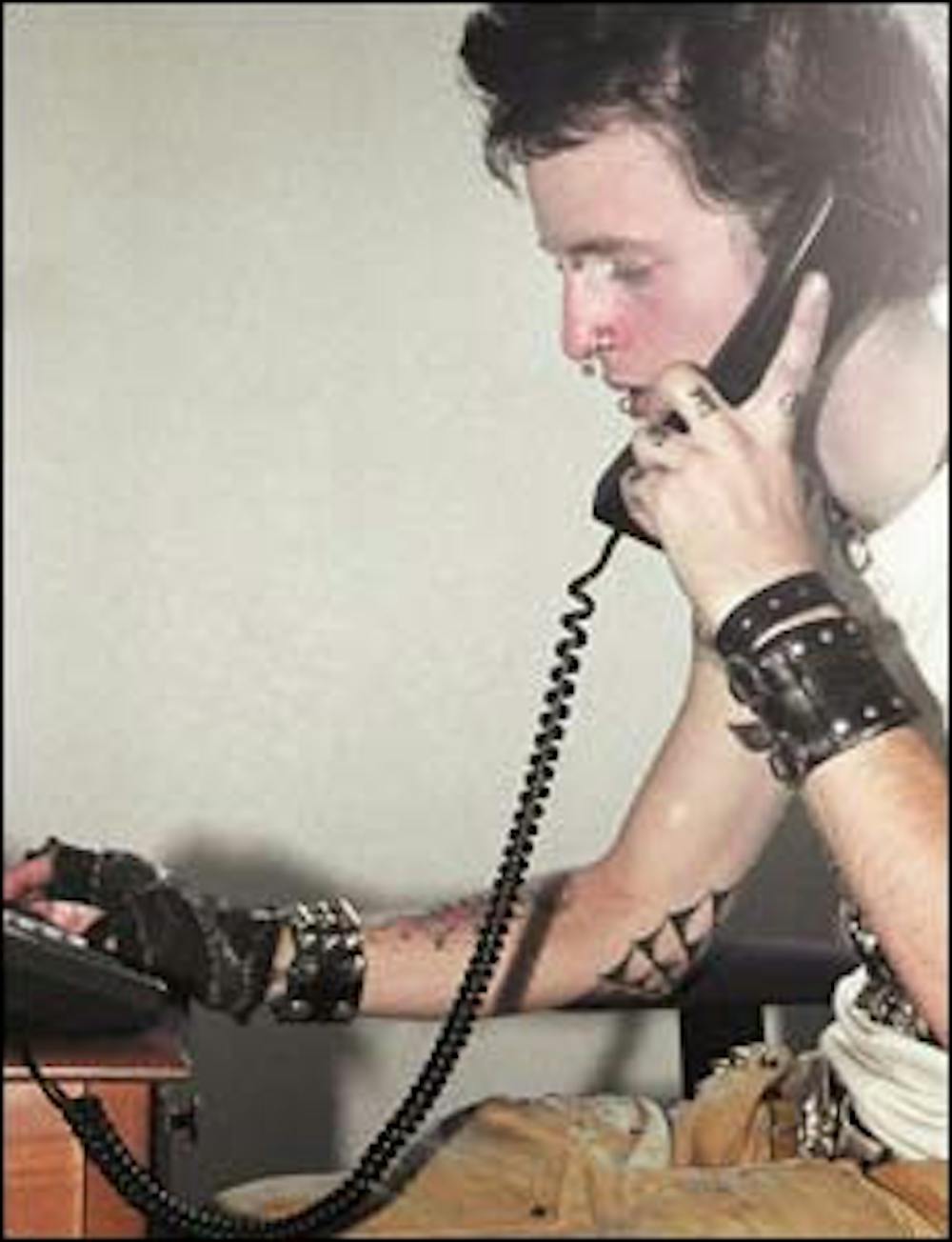

She takes care of homeless people between the ages of 10 and 21 who stop in the center for some food, a place to rest or a free telephone. Some of the youth lack basic living skills, but Connor, 23, who was homeless until about eight months ago, understands.

Connor was born in Latrobe, Pa., where her family was poor for much of her childhood. While Connor said she never went without food, she added that her family was often on welfare.

She said that since she was 15 years old, she spent time in and out of a group home after getting into trouble with the police.

After being homeless for two months and discovering that she wasn't successful at "spange" (asking for spare change) she turned herself in to childcare workers.

"I was a really confused girl at that point in time," she added. "I couldn't take it anymore. I was so hungry."

She said she then spent more time in a group home and after graduating from high school, spent a few years working odd jobs and moving around the country.

Less than a year ago, she moved to Phoenix and found a job at the Phoenix Tumbleweed drop-in center. Two months later, she transferred to the Tempe drop-in center.

"I'm a survivor," she said. "My parents always told me that. I just know how to survive; I have that instinct."

Working with other youth care workers at the Tempe location of the non-profit day center, located adjacent to the Muslim Cultural Center north of ASU, Connor's survival instincts brought her to a role reversal: she has become the caretaker.

"We're the mommas," she said. "We tell them, 'You need to take a shower. You need to wash your clothes. Did you brush your teeth today? What do you want to eat?' "

But while Connor mothers her clients, the mere existence of these offerings points to a larger issue in this suburban city: youth poverty.

The Center is one way Tempe has chosen to handle the problem. Even though Tumbleweed is the first of its kind in the city, its placement in north Tempe brings several concerns to the area.

POVERTY IN TEMPE

She balanced a plate of fresh-grilled patties in her palm and climbed the stairs. The smell of burned meat substitute followed Connor. It wafted from the kitchen of the First Congregational Church up to the church's second floor, where the Tempe Youth Resource Center room is located.

"We've got veggie burgers and veggie sausages," she said, lowering the plate of food onto a table crowded with a tub of potato salad and a bag of potato chips.

She grilled the food for the Center's Good Friday cookout. But four Good Fridays ago, Tempe's homeless youth couldn't have spent their afternoon painting Easter baskets because the Center didn't exist.

The Center indirectly owes its existence to Tempe Mayor Neil Giuliano. In 1999, Giuliano asked the city to review its homeless problems and recommend solutions. Soon after, the Homeless Task Force formed and commissioned a yearlong study of homelessness in Tempe. The ASU School of Social Work carried out the study.

The Tempe Community Council, a non-profit community services organization, found that the city adequately provided for homeless families and people with mental, domestic abuse and addiction problems, despite Tempe's 14.3 percent poverty rate as of the 2000 Census.

Despite Tempe's recent recognition by the National Civic League as one of the top 10 best cities to live in, the city has the highest rate of poverty in Maricopa County and an even higher rate than the state of Arizona.

The city failed, according to the study, to provide for single and young homeless people, who flock to Tempe because of its college-town status and their ability to blend in with the ASU crowd.

Until that point, Tempe had referred its homeless to organizations outside of the city, such as Central Arizona Shelter Services, because the city had no homeless programs within its borders.

The Homeless Task Force changed that, said Kate Hanley, executive director of the Tempe Community Council, when it recommended to the Tempe City Council in its October 2000 final report that a drop-in center be located inside Tempe.

"Our sense of it was the problem is already here and the problem can be more appropriately addressed if you do try to intervene with these kids," she said. "We're all in this together and communities - especially a small community like Tempe - need to carve out a small sliver of the pie and do their part."

Hanley said that after the recommendation they found Tumbleweed to be the type of youth service provider the Task Force was looking for.

However, when Tumbleweed applied for use permit with the Tempe City Council in August, security and other concerns became an issue for businesses near the Tempe location.

SECURITY CONCERNS

"It's the one with the blue handle," one youth said to Connor as she searched through her desk drawer to find the tall, homeless youth's knife.

Knives are prohibited inside the center, but they're fair game outside sight of the youth care workers.

One of Tumbleweed's goals is to attract more youth to the Center, but if attracting more youth means attracting more knives and other security problems, businesses in the area are wary.

Jayne Marecek, co-owner of Yoga Planet, had some reservations when she first heard the Center would be opening about 100 yards away from her business.

"We're here and we've got students coming in and leaving at 10 o'clock at night," Marecek said. "We've got people coming here early in the morning and so there is a safety concern."

Marecek's business partner attended the Tempe City Council August meeting the night it was to approve Tumbleweed's use permit.

Some people from different businesses in the area expressed their security worries at the meeting, but the council voted unanimously to grant Tumbleweed a use permit inside the church with one condition: if security became an issue, Tumbleweed would have to revisit the council for reevaluation. Later this summer, the center will be reevaluated, but barring the unlikely safety mishap, the City Council is expected to extend their permit.

After the meeting, Marecek and her business partner toured the Center and learned the Center's objective of rehabilitation.

She no longer opposed the Center. She said she even offered youth at the Center free yoga and pilates lessons. No takers yet, she added.

"We haven't had any issues whatsoever with them," Marecek said. "No security issues. We would be delighted if they would take us up on our offer because I think yoga would be a terrific thing for the kids."

While Marecek has also donated money to the shelter, not everyone in downtown Tempe is as supportive.

Rod Keeling, executive director of the Downtown Tempe Community, an organization that represents downtown Tempe business owners and stakeholders, said the DTC neither supported nor opposed the Tumbleweed Center's use permit.

Tumbleweed is still in its "wait-and-see" period as far as Keeling is concerned.

"Tumbleweed has a great opportunity to do good in downtown Tempe and to help us," Keeling said. "It also has a great opportunity, if it's not managed properly, to become a real attractant and have kids hanging out there all the time. We'd have this beautiful park we built in front of this expensive condominium building full of homeless kids all the time, which is something that obviously I don't think the community wants."

So far, Tempe's homeless youth population has not increased and neither has its crime rate, Keeling said.

"If it keeps going the way it's going, they're doing good things," he added.

But Hanley sees attracting more homeless youth to Tempe as a good thing. She said she views it as a problem that is better left addressed as a community than ignored.

"The downtown businesses - understandably - were concerned that this was going to hurt their business," she said. "They thought it was going to draw more homeless kids or make it more visible. And so they didn't want to do anything to make the problem worse."

For Hanley, though, Tumbleweed isn't there to make homeless kids disappear off Mill Avenue or eradicate the problem altogether. Tumbleweed is there to deal with a pressing issue and offer to help to those who need it.

"If we do a good job, we're probably going to attract some more kids," she added. "Kids will hear that it's a good program and so they'll come to use the services.

"The way we look at it is: whose homeless problem is it? It belongs to all of us."

Chris Wilson, the DTC's program coordinator, manages its outreach program, which transports homeless people out of Tempe to social service providers around the rest of the Valley.

He said the DTC spends about $50,000 to $60,000 annually on its outreach program and isn't sure if homeless population in Tempe necessitates a Tumbleweed Center. He said plenty of social service organizations cater to the homeless population outside the city.

"The question is: is the population in Tempe large enough to warrant it?" Wilson said.

The Tumbleweed Center is funded mostly by a more than $400,000 grant over two years from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

It has served approximately 140 clients who've visited the Center more than 636 times since November. Some of the youth are runaways from home-the workers at the Center have sent nine of these people back home when it was safe to return.

The Center offers clothes, counseling, legal assistance, laundry, food and help getting correct identification to needy people.

They also offer assistance in getting a job.

Pizzeria Uno is one place where some of the homeless youths may end up working.

Stanley Nicpon, who owns the Mill Avenue location of the pizza franchise, donates fresh pizza to Tumbleweed every Wednesday and places homeless youth in cleaning or serving positions in his restaurant.

For Nicpon, helping others in need is a societal responsibility.

"The purpose of life is not to be the biggest or best basketball player," he said. "The purpose is not to get a $50 million contract for playing for the Diamondbacks. The object of life is really two-fold: to be a useful citizen and pay your bills on time."

He added that he was also skeptical about Tumbleweed's usefulness at first until he learned more about the program.

He said he's had no security problems and youth whom enter a program like Tumbleweed have a much higher success rate reincorporating into society.

"It makes me feel good to help other people help themselves to get on with their life," he said.

TATTOOED EXPERIENCES

Connor still bears some fashions of her former street life: large tattoos color her arms and shoulders.

When she worked as a shop girl in a Colorado tattoo parlor, sometimes the storeowners paid her with free tattoos.

A rose with an eye in the center decorates her right shoulder while flower patterns wrapped around her left elbow and adorn her stomach.

For Connor, most of the tattoos have no significance - even the Virgin Mary who cries blood on her left shoulder. One tattoo, she said, looking down at her chest where it's placed, has meaning.

"This one is the most important piece," she said, pointing to a small bird with an upside down U in the center. "It's the Phoenix bird, which in turn means 'spirit rising,' and on the inside is a Celtic rune.

"It means freedom, strength, courage and wellness."

The implication is that Connor is a Phoenix with strength and freedom and wellness. She lives on her own in a one-room apartment and has a steady job, a boyfriend, no drug habits and a healthy lust for life.

It wasn't even a year ago that she didn't know what struggles lay ahead on the streets.

Now, working with the youth at the Tumbleweed Center, she said, reminds her of where she never wants to go again. It also inspires her to achieve her goals of settling down and going back to school, something she wished she could translate to the people she sees every day.

"I wish I could open their eyes. I honestly wish I could put their hands on my head to see what I've been through, see what I've conquered, see what I've learned to better myself."

Facing Connor's past and seeing her current incarnation, she explained, might give them hope to survive and to pull themselves off the streets.

"When you're in that mindset, you don't feel like anybody knows what you're going through because you're going through a lot of hell," she said. "Why I like to work with kids is because I know what they're going through.

"I feel like I'm giving something back and I know how to help these people out."

Reach the reporter at ilan.brat@asu.edu.