Flora Jessop knew early on the life she was living wasn't normal. In her community, girls sometimes no older than 12 would marry older men. And more often than not, they were either cousins or uncles of the children, and already had a spouse.

The escalating saga of ridding Arizona of polygamous marriages has recently saturated the media. Every page you turn, every news channel you watch, state officials are campaigning for better enforcement against a practice outlawed in the United States.

It is easy for the public to identify the practice as one done by a small, sheltered group of people, but for those attending the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in the town of Colorado City, multiple marriages are rooted in a history and tradition.

In this quiet community of northern Arizona, there is child abuse, statutory rape and welfare fraud-this is what the public usually hears about.

However, those who have been on the other side of the fence live a different reality. On a deeper level, there is rage, confusion, mind-control and loss of faith in God and life itself in the most unfathomable fashion. Physical repercussions including drug and alcohol abuse only show a small part of the emotional and spiritual decay of those involved.

Jessop has been through such experiences and has managed to come out on the other side. The story of her life reflects both the legal and emotional crisis of polygamy that happens in the towns of Colorado City and Hildale, twin cities on the Arizona and Utah border.

She offers one woman's account of the fear and deceit of a polygamous community-a community that has been hiding behind the sanctity of religious freedom and lax laws so that its members can commit illegal acts and emotional crimes.

Learning to keep quiet

The group specifically practices polygyny (more popularly referred to as polygamy), the condition or practice of having more than one wife at one time-only men can have more than one "spiritual" spouse. This fundamentalist group was excommunicated from the mainstream Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which does not condone polygamy, about 100 years ago or, at about the same time Utah became a part of the United States.

In order for Utah to be accepted into the Union, it had to ban polygamy, but this didn't do away with the practice.

Today, there are about 55,000 practicing polygamists in both Utah and Arizona.

Jessop's mother married her father at the "late" age of 20 as his first wife. Jessop's father had a spiritual marriage with her mother's younger sister as well. Jessop herself is one of 17 children and has three older siblings.

Jessop remembers that although her mother never said anything against the life she and her children were living, she was terribly unhappy.

"I know that when she was alone in bed at night, she would cry, but she never dared to tell my father that she was unhappy," Jessop says.

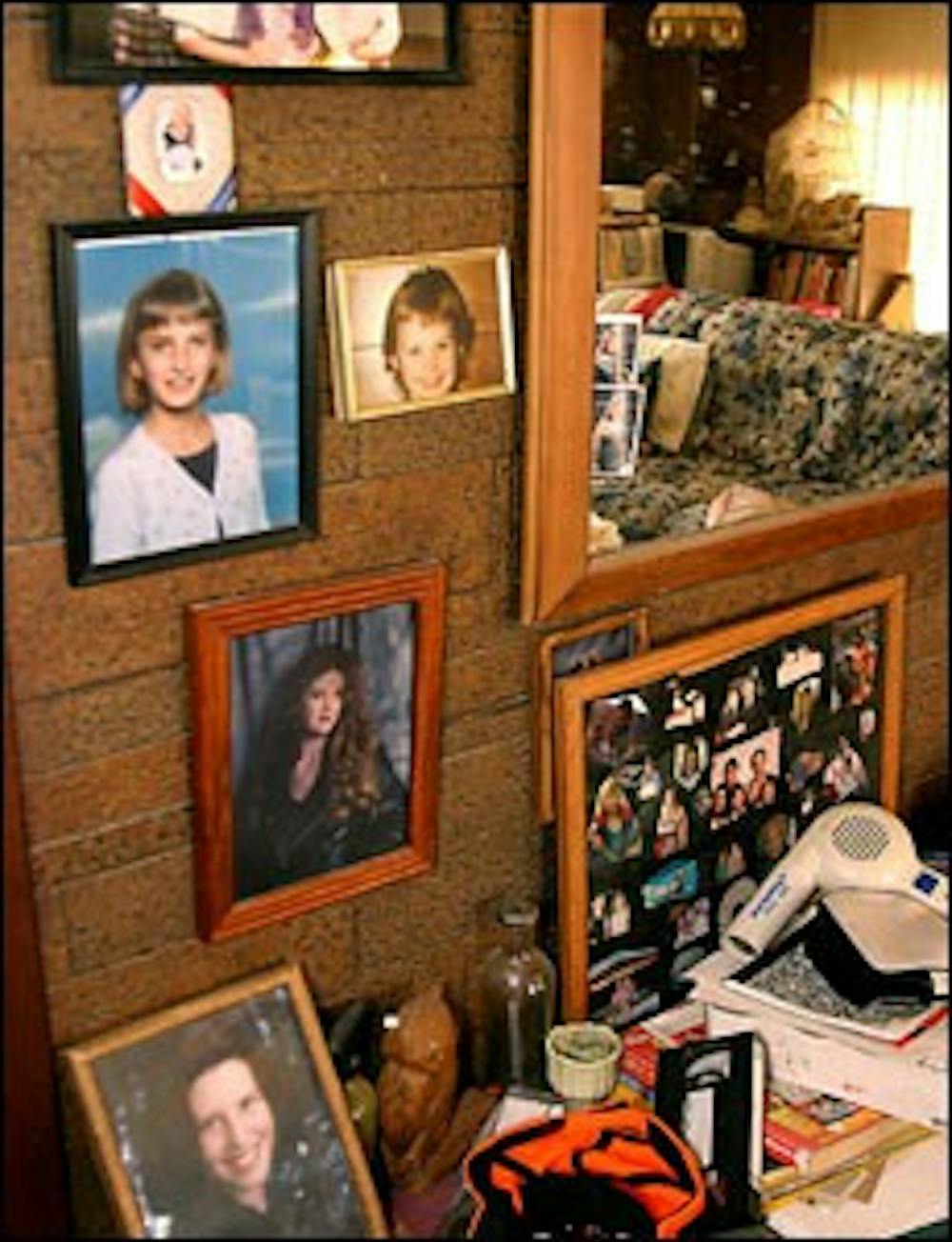

A slight woman with light eyes who speaks about her personal experiences hesitantly, Jessop didn't know what made her different from other children who were being abused. She credits her grandmother for planting the idea of freedom in her head.

Jessop was about 8 years old when her father started to sexually abuse her. The initial stages of inappropriate touching quickly grew into full-blown abuse by the time she was 11.

"There is a strange relationship that occurs between a sexual abuser and his victim," Jessop says. "It's a love/hate relationship because you realize that the one person in the world who is supposed to protect you from all the bad guys in the world is the one who is hurting you. But, with incestuous sexual abuse, as a child you love your father, and you want him to love you back."

Regardless of the love she felt for her father, Jessop knew she could not live in the situation any longer. No one supported her aspirations to leave, but she did find some solace within her family.

"My grandmother wasn't raised in the family. She was married into the group, so having seen the outside world, she taught me that my self-worth did not hinge on who I married."

So, at the young age of 13, Jessop took her father to court for sexual abuse. However, her first attempt for protection or freedom proved fruitless when she was sent to live with her uncle, her father's brother.

Jessop's inability to get proper help from authorities in the community illustrates what has kept many polygamous towns from facing any prosecution or consequences for their practices. Most polygamous towns get away with such atrocities because the existing police department answers to the local religious authorities.

"It takes a lot of courage for an abuse victim to step forward and ask for help, however, in these communities, you are taught your whole life that law enforcement is your worst enemy so you really don't trust anyone," Jessop says.

And as it proved for Jessop, dialing 9-1-1 during an emergency can often make things worse.

Consequences of a not so close encounter

"I was basically under house arrest for three years while my uncle tried to beat Satan out of me," Jessop says, her voice quiet but her confidence evident.

Rather than letting her mind and body be completely subservient to her uncle, Jessop became immune to the threats. However a combination of mind control and a restriction of education were evils that would affect her later on in life, as it had other women in the community.

"I was told that if I left the community, or was out-of-line, that I would end up as a harlot, or a druggie or an alcoholic," Jessop says. "The problem is that is when you are told these things, and you actually get out of the community, you turn to drugs or alcohol because you think that is the only other option you have."

Rowenna Erickson, a former polygamist wife and a current member of the Tapestry Against Polygamy activist group, says that the goal of the mind control is to damage a woman's sense of self-worth.

"The men control women through deprivation of education, knowledge and power, and this reinforces the fear that if you don't follow their orders, you won't go to heaven," Erickson says. "It was easy for men to justify women who got bent of shape by saying they were just an angry bunch of bitches or something to that extent."

Education is another source of power men in these communities control. Jessop herself was pulled out of school in ninth grade. Although men in these communities lack basic education as well, and many never even attend high school, the goal is to ensure the women have a limited education.

Regardless of her formal education, Jessop knew she needed to get out Colorado City, so during a group trip to the dentist, she took the opportunity to run. However, she happened to run into Phillip, another of her father's brothers who had been coming into town for a priesthood meeting. They were caught talking on the main road, an act members of the fundamentalist community considered to be a form or sexual relations since this man was neither her father, brother or someone in her immediate family.

As a result of this brief encounter, Jessop was given a choice to either marry him or go to the state mental hospital.

They were married the same day. She was 16, he was 19.

Fleeting faith

Just when it looked like life was falling back into darkness, marrying Phillip actually turned out to be a blessing in disguise-not only was he much closer to her age than any other man she might have married, but when she asked to leave the city and their marriage, he supported her.

"I had a lot of love for that man because when I wanted to leave, he let me go," Jessop says.

In a community where the men have both physical and mental control of their wives, Jessop's intention to leave was not only looked down upon, but came as a risk to the entire community. She would be setting an example to the rest of the women and could give them ideas to do the same. So, although Phillip allowed her to run, church officials closely tracked her moves.

"The mind control was so good-if you were to leave, you would only have guilt and fear in you," Erickson says, "and they (the men) could get you to do anything."

And "anything" includes lying to law enforcement about the father of your child to claim welfare checks and food stamps.

At the age of 16, Jessop ran and headed to Las Vegas, to stay with a childhood friend. She thought she had escaped a life of sexual abuse until her father's friend raped her and asked Jessop to become one of his brides. Seeing she could not find shelter or safety anywhere near Utah, Jessop ran to Missouri. However, the men of Colorado City were never far behind.

"That was when the men of the community really started coming after me," Jessop says. "I ran from them for almost five years."

In those five years, Jessop drifted in and out of jobs and got mixed up in drugs, almost killing herself with cocaine. She not only felt physical pain, but the emotional trauma she experienced lead her to lose her divine faith.

"I hated God for many years after I left," Jessop says. "At that time, I would have spit in the face of God."

She was constantly running from California back to Missouri, where she became pregnant with her daughter. Jessop decided to move to Phoenix and attempt to start her life over again.

Believing again

Jessop, now 34 and a prominent activist, is living a much more stable life. She says much of her strength comes from her 13-year-old daughter, Shauna. She also credits Tim, her husband, and Carol, his mother, for helping her to realize "evil done to children has nothing to do with God."

With regard to her faith, Jessop believes in God again, but not in organized religion.

"I personally think that giving a man power over who you believe you are, or supposed to be, breeds corruption. I've seen too much abuse in organized religion."

Since taking her fight public, Jessop has not been allowed to speak to her mother or any of her siblings for the last four years. One regret she does have is that her daughter doesn't know her own family.

"Shauna is very aware of what I do and very aware of my family, but she doesn't know them well, and I find that unfortunate," Jessop says.

Jessop has channeled her misfortunes into helping others who are fighting to get out of the situations she went through. She is currently trying to help her younger sister leave the community, but the inability to communicate with her has slowed the process.

As recently as Jan. 11, Jessop helped two young girls, Fawn Louise Broadbent and Fawn Holm, both 16, escape from Colorado City. She drove them to Phoenix, but the two girls, who feared Child Protective Services would return them to their families, ran away again. They are still missing.

Jessop herself may face kidnapping charges, but she is undeterred by the threats.

"Cuff me. I'm willing to lay my life down for these children because I know what these kids face when if they go back."

When speaking of her activism, Jessop's voice becomes stronger and passionate, and she is quick to define her efforts: she is fighting child abuse, not polygamy.

"Fighting polygamy can be a lost a cause because of the freedom of religion issues, but you can't claim religious freedom in child abuse."

She sees education as a key tool in her efforts to get women to realize that life in polygamous marriages is not their only option.

"They need to enforce education laws and put those kids that were taken out of school back into the public education system," Jessop says.

Jay Beswick, a former tri-state representative for children in abusive homes, says state officials should be aggressive in their approach to get rid of polygamy, but should also be aware of the sensitivity of the victims.

"The people in these communities have been taught to mistrust authority and outside society," Beswick says. "The first officials to respond need to understand the culture these women and children have been brought up in."

Jessop agrees; "Polygamy is organized crime and there is no other way of looking at it."

Although Arizona officials are beginning to take larger steps in prosecuting individuals of the community, Jessop vehemently denies any real steps have been taken.

"I want action, not words, and, until then, I'll do what I can to keep these kids safe."

Having been through all she has, Jessop says she can't explain her good fortune.

"I don't know what made me different," she says. "I was just lucky."

Reach the reporter at rekha.muddaraj@asu.edu.