EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the second in a series of in-depth, first-person essays.

Ya'ateeh, shi ei Crystal Begay yiinishya'; To'ahanii nishlii, Ta'neeszahnii bashishchiiin, Naa'neshdeezhi tachiniii da'shiicheii, Maii'deesghiznii da'shi nalii.

Hello, my name is Crystal Begay; I am born of the People Near the Water, born for the Tangle People clan, my maternal grandfather's clan is Charcoal Streaked, and my paternal grandfather's clan is Coyote Pass clan. I am a second-year graduate student at ASU. I was born and raised on the Navajo reservation, in a little town called Ganado, in Northeastern Arizona. I was raised in a traditional home, with our Navajo language and cultural teaching playing a pivotal role in how my siblings and I were raised. As a Dine, which means "The People" in Navajo, I've participated in many ceremonies; but now I am returning home for the first time to observe a ceremony for complete strangers.

Coming of age

It's March 18, 2005. Cassi Clah's spring break is about to begin. Unlike her friends, Cassi won't be spending her break hanging out or taking a trip with her family. Instead, she'll prepare for and participate in the Kinaalda Blessing Way, one of the most physically and mentally draining activities a Navajo girl will ever participate in.

Cassi is a junior at Ganado High School, in Ganado, Arizona. Ganado has one hospital, one gas station, one grocery store, one Laundromat and not a single stoplight. Cassi's family - her mother, Angie; three sisters, Tisheena, Michelle, and Tiffany; and little brother, Quietin, live in a two-story home in a smaller neighboring community called Kinlichee, which is 5 miles east of Ganado.

A Navajo girl cannot participate in her Kinaalda until she begins menstruating.

When Cassi got her first period in February, her Kinaalda was announced. Finally, it was Cassi's turn. At 16, Cassi is considered a late bloomer for the Kinaalda ceremony; young girls usually participate in the ceremony around the age of 13.

The Kinaalda is a four-day and three-night "coming-of-age" or "rite-of-passage" ceremony for young girls. It signifies the child's entrance into womanhood. It is said that Changing Woman (Asdzaa Nadleehe), the procreator of the Dine people, was the first to participate in the ceremony. She was named Changing Woman because within four days of her birth and discovery by the Holy People, she became pubescent. In order to sanctify her maturation and blood flow, the Holy People planned and conducted the ceremony on her behalf.

I still remember mid-February in 1995. One of the biggest days in my entire life as a Navajo woman had just happened. I had gotten my period. My sister was the first to know, only because my mom wasn't home yet. The next day, during first-hour math class, I slipped a note to my friend, Shynowah, telling her, "I'm a woman now." It goes without saying that I was totally thrilled and proud.

Cassi stands just a little over 5 feet. She's thin, but her round, thick cheeks resemble a baby's face.

Once Cassi got over the initial shock of her first menstrual cycle, she became anxious because she did not understand the history and significance of the Kinaalda or the fuss over the preparation for it. She was too young to remember her oldest sister's ceremony, and her other sister's ceremony was planned, but never happened.

Keeping traditions alive

Nobody had really explained the Kinaalda ceremony to Cassi.

That is not unusual. Helen Williams, a Navajo Culture teacher at Ganado Middle School said she believes that is the reason many girls do not want to participate in the ceremony because they simply are not aware of the purpose and significance the ceremony has in their lives. For that reason, she includes a unit specifically on the Kinaalda, hopefully to encourage girls to participate in the ceremony when their time comes.

Plans for Cassi's Kinaalda took shape about a week after her first cycle. Cassi's mother phoned Cassi's grandmother, Yazzie, and asked if she'd tie Cassi's hair. Yazzie agreed. Tying the hair for a girl at her Kinaalda is significant. In the Dine culture, the hair represents rain. Tying the hair puts one's mind into focus as the girl enters adulthood. Each family requests a woman to tie the hair of the Kinaalda celebrant. The tying of the hair signifies the beginning of the Kinaalda, but that's not all the hair-tier does. She also becomes a mentor for the young woman during her ceremony and throughout life. The family of the girl typically looks for a woman who has good character, culturally knowledgeable, about the Kinaalda.

Yazzie is also known for her skill in making aPIkaan, a ceremonial cake made of corn and water, and sometimes sugar and raisins. The cake is baked in a large hole in the ground, on the third and final night of the ceremony. The cake is intended to honor Mother Earth.

My mom decided that one of my grandmothers on my grandfather's side will tie my hair. Although I never met Grandma Bahe, even when she helped at my cousin's Kinaalda, I didn't argue with my mom's decision.

Grueling routines

It is Cassi's Kinaalda day. Cassi's family has bought new jewels for the event: a pair of traditional turquoise earrings, a red and white woven sash belt, a concho belt on top of sash, two bracelets and a silver ring inlaid with turquoise. Even though Cassi arrives wearing a little mascara, she will have to say farewell to the things she likes about the dominant culture - including her makeup and her favorite rap artist, Tupac, as she steps into world in which she's always lived but has never really known.

Cassi puts on her velvet fuchsia two-piece traditional outfit. Her top is long- sleeved with a collar; her skirt is a three-tiered ankle length skirt. She doesn't wear her moccasins yet. She can't put them on until after her grandma ties her hair, so for now she's walking around in her white K-Swiss shoes.

Everybody migrates to the hogan from the house.

Cassi sits on her knees on several blankets and faces east towards the door. She sits behind the stove, which is located in the center of the hogan. Yazzie begins to tie her hair by brushing it with a Navajo brush, which is made of hundreds of strands dried grass. She pulls all of Cassi's long, light brown hair into a low ponytail and ties it with a piece of buckskin. She leaves a few strands of hair out in the front, to prevent Cassi from going bald later in life. Afterwards she helps Cassi put on her jewelry. Cassi puts on one necklace first, and then her grandma adds another one so she'll be blessed with good wealth. Her moccasins are next.

Cassi lies down on her stomach with her head facing east and her arms stretched out to the side. Yazzie takes her own weaving tools and holds them in her hands as she begins to massage and mold Cassi, who is considered so fragile and soft she must be sculpted into a strong woman. She starts at Cassi's head, so her mind will remain clear and focused; then to her arms, then down her back so she'll have good posture. She squeezes her stomach so Cassi will stay thin, and then massages her legs and feet so they'll be strong and sturdy.

And Cassi needs strong and sturdy feet and legs, because now she must run. She leaves the hogan and runs east. Her siblings follow. She will run two times a day, increasing strength and speed and distance each time. The running is a mental and physical test for the girls to help them get strong. Later, Cassi will have to run around a tree. Usually the tree is young, and shows uprightness and sturdiness, which ensures Cassi will grow like the tree.

Additional challeges continue for the duration of the ceremony. On the third day, Cassi begins to help baking a ceremonial cake from ground corn. She uses a traditional grindstone to produce a 25-pound bag of ground corn. Unlike Changing Woman, modern Navajo girls do not usually grind all the corn. Instead, they take their corn to places with modern grinders. Cassi's was ground at a feed store.

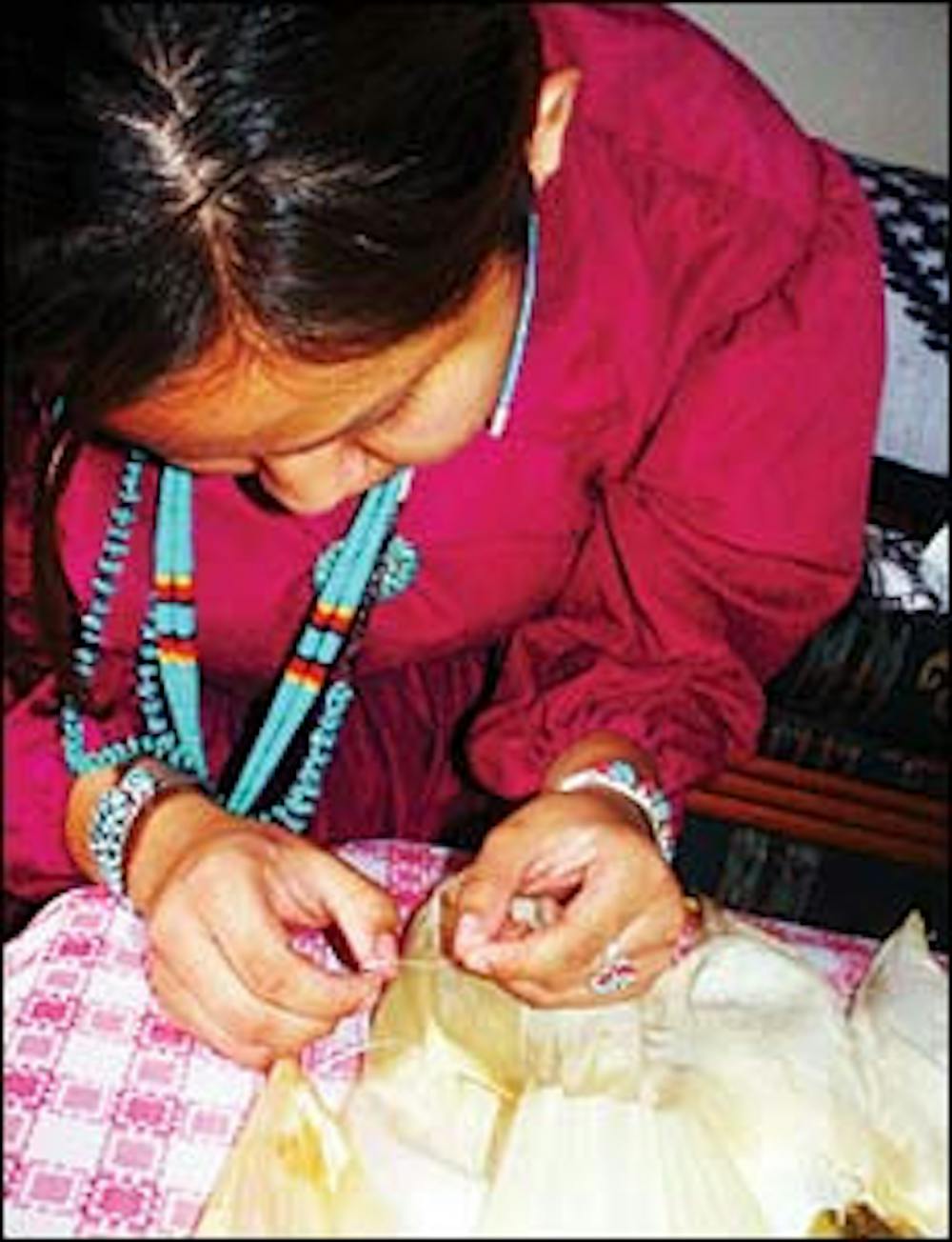

The men help build a fire while the women stay inside to sew cornhusks together. The husks will separate the cake from the ground corn at the bottom and side and at the top from the fire.

As the sun rises on the fourth and final day, the men take the fire and ash off the cake to let it cool down. When it does, Cassi begins to cut the cake and take the pieces out. Once the cake cools off, it is taken inside the hogan. Everybody goes back inside the hogan also. There, Yazzie mixes water with white clay. With two strands from the brush, Yazzie puts the clay on Cassi's face. Cassi paints Yazzie's face and then does the same to everybody else to renew their own spirituality. Cassi lies on the blankets in front of the hogan to be molded and massaged as she has been throughout the ceremony. Personal belongings, like keys and wallets, are strewn on the blanket to be blessed.

Cassi gets up and begins to bless the others. She stretches the kids, beginning at their feet and moves up to their head and literally tugs at their head toward the sky, so they grew tall and strong. The adults request to have their stomach squeezed so they can lose weight. Cassi gives away pieces of the cake, dishes, soda, shampoo, conditioner and lotion. The giveaway shows the young lady's appreciation for all those that helped throughout the ceremony. The Kinaalda celebrant is not allowed to eat her own cake. Otherwise, all her teeth will fall out. The center of the cake is the most sacred, so Cassi gives it to the medicine man and Yazzie.

After the giveaway, Cassi is a changed woman, almost. She no longer has to run twice a day. She can return to eating sweets, drinking soda, and using salt again without the concern of losing her teeth.

A dual life

The next day, Cassi returns to school and goes back to watching MTV and listening to Hip Hop and R&B. She luxuriates in taking a shower, since it is no longer taboo. But mentally, she feels stronger. She knows she can accomplish and overcome, the sacrifices and hard work she had to overcome proves she can. She's proud to be a Navajo woman prepared for all the responsibilities associated with the identity. Cassi will encourage her younger sister Tiffany, who is approaching the age of a Kinaalda, to also learn about the identity and obligation of a Dine woman.

It is said that days after Changing Woman's Kinaalda, she gave birth to twin warriors called Monster Slayer and Born for Water. For modern Navajo women, the outcome of a Kinaalda may not be so dramatic. What they receive from the Kinaalda, instead of warrior twins, is a sense of identity and obligation.

It'll be ten years this April since my Kinaalda, but I can't recall the moment of epiphany when I realized I wasn't a child anymore. Still, a decade later, I can see the child I once was, sleeping with my mom, when my dad's away or when I'm just lonely, and giggling excessively with my sister; but I know I'm not. I moved away to go to college six years ago, and instantly inherited four sons (also known as my three older brothers and nephew), and I spend most of my time cooking and cleaning for them like my mom did. I find myself more concerned with whether the house is cleaned or if my nephew ate, but I also never forget to grab tickets to a concert by my favorite band, Killswitch Engage. Growing up and growing old are a paradox. The distinction between them remains clear in my mind. It's very similar to being a Dine woman in an Anglo-American society.

Even though I knew the history and purpose of the ceremony, seeing Cassi go through it had a deeper meaning. My Kinaalda, I realized, prepared me for the obstacles I have faced - like the death of my beloved grandfather, or the pressure of working and going to an Anglo graduate school.

But despite these strengths, watching Cassi's ceremony 10 years after I had my own Kinaalda made me realize I am not even half the woman I was meant to become in those four days.

Reach the writer at crystal.begay@asu.edu.