EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the third in a series of first-person essays written by ASU students about unique and influential experiences.

When I first arrived in Stellenbosch, South Africa, in fall 2004, it was hard to convince myself that I actually was in Africa. The quiet town seemed to be made up almost entirely of university students and South African wine farmers.

The buildings in Stellenbosch are mostly milk white and blanketed with black, thatched roofs. The streets are lined with oak trees, reportedly brought by founder Simon van der Stel in the late 1600s. A river meanders through the expensive tourist shops, ethnic restaurants and classic, Dutch-style buildings of the University of Stellenbosch.

The town sits between the foot of the rain-drenched Jonkershoek Valley and the soaring peak of Stellenbosch Mountain. There are no parched veldts made popular by authors and filmmakers over the years. Instead, there are lush, manicured vineyards that climb the hillsides like pinstripes.

It was not this sort of gentrified Africa that I had come to explore. Even though I had known from pictures and brochures that Stellenbosch was a beautiful town with a strong European influence, I was searching for the Africa found in the writings of Hemingway and Conrad. I was a 21-year-old Arizona State University exchange student who had come in search of a place that was still raw -- where people with potential had been overlooked, and where the place itself had elements of danger and intrigue to it. I wanted a place were I could help people and be liberated from the safe, day-to-day routines of my life in Arizona. But what I had gotten myself into was an overtly European country town.

And yet Stellenbosch was Africa. Its people, both black and white, were African. The wine, made from grape vines long ago imported from Europe, was African. But I was still struggling to understand that I was in Africa. As another American student put it, "I feel like I can't write home and tell anyone about school here. Its like I'm cheating my way through an African journey."

I felt guilty being so comfortable and safe in Stellenbosch, when in fact I'd come to Africa to help those who were not so comfortable and safe, and that guilt led me to join a program known as the Kayamandi Project.

Organized by Stellenbosch University, where I was studying on an exchange program, the Kayamandi Project gave university students and faculty an opportunity to work with poor elementary school students in the nearby township of Kayamandi. I had hoped that somehow this would take me to a more real Africa.

New beginnings

When I first arrived in Stellenbosch, I learned that the University produced many of the architects of apartheid -- the forced segregation of blacks and whites that blighted South Africa for more than 80 years. Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, who is sometimes known as the father of the movement, was one of them. The University is also South Africa's last Afrikaans-speaking university. Afrikaans is the language of the Afrikaners, descendants of Dutch settlers who created apartheid. Afrikaans is still thought of by many black Africans to be the language of the oppressor.

It seemed to me that the university was an unlikely institution to organize the Kayamandi Project -- a group that tries to prepare black children for higher education and the eventual entrance into the white-collar job market.

The project takes University students into Kayamandi Township to tutor and interact with children at Ikaya Primary School. The project is managed by a 21-year-old American nicknamed "Skate or Die Mike Braii." Mike, tall and thin, with pale skin and curly brown hair, often carries his well-worn skateboard with him. Mike's back is tattooed with the wisdom of African missionary Dr. Albert Schweitzer: "Whoever is spared personal pain must feel themselves called to help in diminishing the pain of others. We must all carry our share of misery which lies upon the world."

The former skateboarder and film student, whose real name is Mike Leslie, had come to Kayamandi in the fall of 2003 and was put in charge of the program the following semester. Like me, he had come to Africa to make things better.

When Mike first began to visit the primary school, he felt terribly guilty about the money he had. He asked himself whether the program was really accomplishing anything. A year and a half later, Mike began to feel the group was making a difference. Some of the primary school students had gained confidence and had learned more English.

"When I first came to Stellenbosch and I would see kids at the store or in the street, they would sort of look away and avoid me," he said. "Now, they come right up to me and say 'hello' and we talk. To me that's huge."

Pleasurable home

On my first trip to Kayamandi, Mike took me and nearly 40 other students into Kayamandi Township to meet with the primary school kids. We formed a caravan of three wide, white vans. I was crammed into a corner in the cargo area, sitting against the white metal sides of the vehicle and on the brown nylon upholstered floor. The tire well pressed against my back as I looked out the back window.

Once we'd left the university campus, spacious Dutch-style homes turned to dull brick apartments, and quaint country shops turned to grocery stores filled with large troughs of produce and sullen black faces.

As we got within sight of the township I squinted as the sun peeked out through the clouds. We passed a yellow trailer upon which two black figures had been painted -- one with braids, the other with a high-top fade. It was a barbershop. I ran my fingers through my own mop of brown curly hair and considered going there for a cut some day.

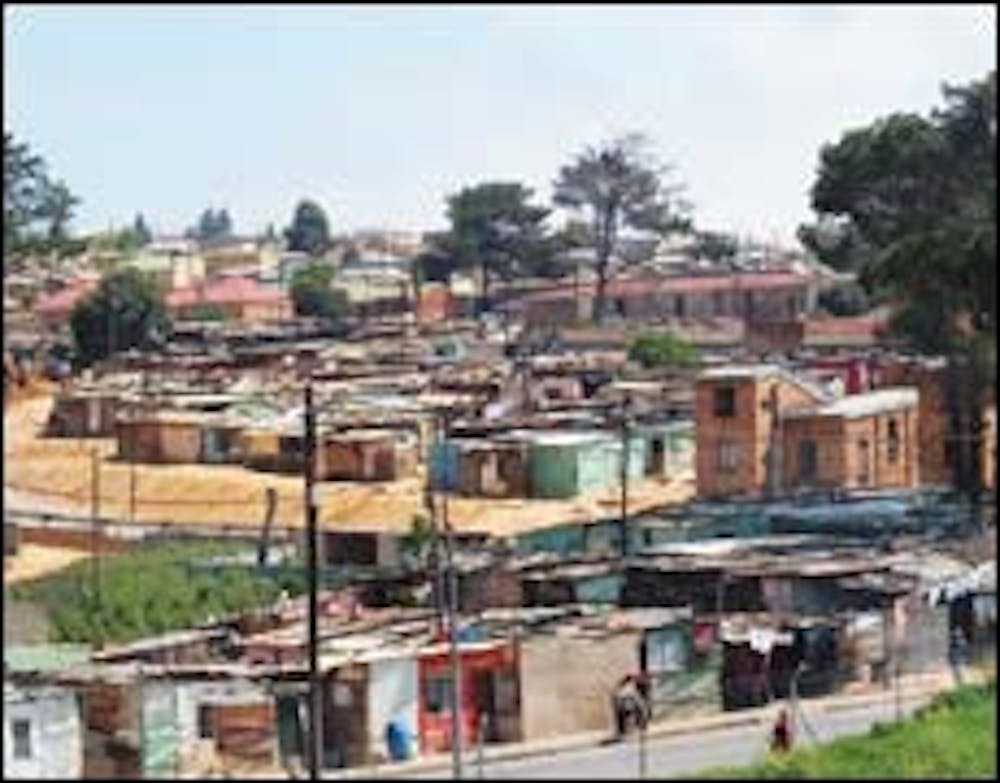

The trailer backed up to a set of railroad tracks, and beyond the tracks was the hill upon which Kayamandi Township rested. At the base of the hill was a field consisting of brown spots of mud patchworked with green grass. Next to the field was a large cement slab. Half of it was a basketball court donated and constructed by former university students. The other half of the slab was bare. I decided I'd work with the kids on the court, perhaps giving them a little more self confidence and a new friend.

Next to the concrete square, shanties protruded from the hillside like small, wooden cliffs. These were the homes of the township people, made from scrap metal, garbage and wood. Further up the hill sat a handful of government housing units -- two-story apartments painted white but still dirty, even in the rain. It is estimated that nearly 22,000 people live inside this square kilometer of hovels and sparse cinderblock apartments. The exact number of residents is unknown because many members of the community are transients who migrate to and from different townships in search of work. Almost all of the residents of Kayamandi are black, and the majority of them trace their roots to the Xhosa tribe, which is the majority ethnic group in this province. The name "Kayamandi" means "pleasurable home," in Xhosa.

Mike drove past a cinderblock wall that has been painted by residents. The wall showed children of all races playing in the sun and preached AIDS awareness and education -- about one in every five people suffers with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. At the foot of the wall was a series of newly planted flowerbeds. If it were up to Mike, those precious rands that were spent on the wall and the landscaping would have been spent on more housing, AIDS-awareness classes for children or expensive medicines to slow the progression of AIDS, the greatest scourge on sub-Saharan Africa since apartheid and colonialism.

Black men walking the dusty road stared at our white faces and wide eyes. The shacks where they lived were fabricated out of almost anything -- walls were constructed of beer signs, food boxes and election posters. A woman sat outside one shack cooking with a metal pot that hung from three sticks over some small burning cinders. An outdoor butcher scraped brains out of a goat's head. Flies buzzed, and the dried blood had stuck a piece of newspaper to his shoe.

As we drew nearer to the school, we saw children in their blue uniform windbreakers, with dark-brown trousers and stiff, gray shirtsleeves poking out. They recognized Mike and waved to him. Mike returned the greeting with an enthusiastic voice that wasn't at all condescending, but instead friendly and welcoming. We all followed Mike's lead and began to wave from our different seats in the van. Some students ran off toward the school in an attempt to beat us there, while others shyly waved and continued on toward their homes. I wondered if they were leaving the school because they didn't want to play with us, or if they had some sort of familial responsibility to which they had to attend.

Wrestling with AIDS

I was excited to meet these kids. As soon as I climbed out of the van, I grabbed one of the donated soccer balls and began dribbling it like a basketball in the parking lot. I could see the main classrooms sat on two giant hillside terraces. The entrance to the school was a gate that went into a large dirt and cement courtyard. The place smelled of urine, a symptom of too few toilets for a population this size.

The children were scattered throughout the courtyard. I continued to dribble the ball, beating a sustained rhythm. Two boys drank from a waist-high spigot that served as a water fountain. Another set of boys sat on the concrete steps. The boys shared a plastic bag filled with a corn meal snack called mealy. The pale yellow meal stuck to their faces.

Soon more kids came out to meet this semester's group of white strangers, who had money and spoke English and could get sunburned. The children all looked well-fed and healthy, but also a bit dirty and dusty. They looked like regular little kids who got into trouble and liked sweets more than schoolwork.

The first child who came to me was Anele Nowembu. He was a seventh grader and the next year he would begin attending Kayamandi High School. I'd met him the day before at Mike's house while getting oriented into the Kayamandi Project. He was short for his age and a bit more round than some of his classmates. He wore a yellow Philadelphia T-shirt that Mike had given him and a pair of long jean shorts. Anele had been coming over to Mike's house for the past six months for extra help with his English and to play cricket and Playstation games with Mike and his roommates.

Anele explained that a lot of students had been sent home because the teachers thought we weren't coming due to the rain. A few kids had stayed in the classrooms just in case. Because the fields were wet, I handed Mike the soccer ball and went in to meet the kids.

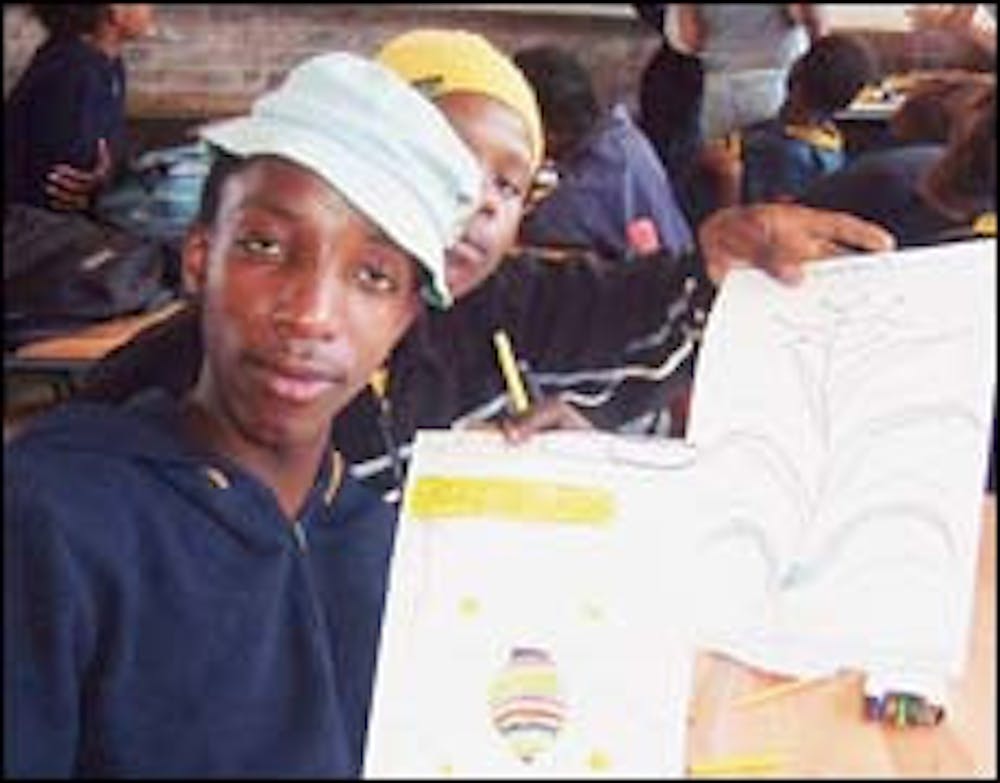

The classroom was simple, with a long head-high window on the side opposite the door. The walls were plain and brown. On the floor, I saw a cluttered pile of paper, dirt and debris. As we entered, some students climbed on their desks and began to dance. Others came directly up to us and introduced themselves. The university students did not shy away from the children. They embraced those who asked for a hug and gave out dozens of high and low fives. Many of the university students sighed about how adorable the children were.

But I wondered what we were doing there.

Some children seemed generally afraid of me. I wondered what I was doing wrong. I had come here to work with these kids and be their mentor and friend, but they seemed terrified of me. I played an airplane game with one boy, who broke away from me fearfully. I was stupefied, and unsure of my mentoring skills. Did I make a culturally inappropriate airplane noise? Should I have treated this kid more like an adult? Should I be more concerned that I needed a haircut?

I decided to go outside and try to organize a sports game despite the condition of the field. Sports were something I felt I knew about, and I hoped it would make making friends easier than my first airplane-game introduction. Mike explained that the kids had mistaken me for an American wrestler. The notion of me, 6 foot 3, 150 pounds, scaring off the kids who I wanted to help because they thought I was a professional wrestler seemed silly, but it made me uncomfortable.

I began dribbling a basketball in front of a group of very small kids who had gathered outside the classrooms. They smiled and chased after it. Soon a good mix of university students and kids walked down to the basketball court. We passed several people on the way. I smiled at all of them. One man ignored my friendly gesture. I began to wonder just what the residents of this street thought of seven rich, white university students walking through their neighborhood with 10 of their smiling children in tow.

The basketball court was littered with glass and garbage. Some kids were already playing in the corner of the cement slab. One had a shaved head and a strange sort of furry coat. Above his eyes, where his eyebrows should have been, he wore red paint. To say the least, the boy stood out, and I assumed for some reason he did not attend the school. But he seemed to need the same help and care that all the other kids did, so I was more than willing to let him play.

As some of the university students chose teams for a game, I tried to remove as much of the glass and debris from the court with my feet. A number of the university students carried backpacks. They removed them, placing them in a large pile just off the court. Keeping them in plain sight meant it was less likely someone could steal them.

The game began. Quickly, the rules were forgotten. Older boys traveled up and down the lanes, only dribbling the ball when they attempted to do a trick. They tried going between their legs or behind their backs. Since I was chosen to officiate the game, I let this go as a tradeoff for being allowed to pick up the small children who couldn't throw the ball hard enough to make a basket, empowering them with the ability to dunk. Besides officiating and serving as a human elevator for the small children, I also announced the game, with the hope that perhaps the kids would learn some English through immersion. Or at least they would laugh at my silly comments.

Soon, each player had a nickname. A tall, older boy with a dark complexion quickly became known as "The Goods." He looked very much like Lakers' forward Lamar Odem. Another student, Bosika, a close friend of Anele's, wore a blue knit sweater over his broad, strong shoulders and a pair of black trousers. He became known as "The Playmaker" for his love of handling the ball.

Bosika was a seventh grader, and he sometimes drove a minibus taxi between downtown Stellenbosch and Kayamandi to make extra money for his family. Another boy, Syabunga, was taller then Bosika, and thinner. He wore an American flag like a bandana on his head. We called him "Lex Lugar," after an American wrestler who wore the same headpiece.

The game was interrupted when the child with the red eyebrows fell to the ground clutching at his foot. A small trickle of blood had begun to run down his foot. He had stepped on a piece of glass.

I looked at the child. I looked at the blood. I didn't know what to do. The other students stood helplessly looking at the blood and the boy. We were concerned. We felt one of us should comfort him, but we didn't want to get AIDS. So we stood back.

The boy's friends never once looked to us for the guidance we had come to offer, or the help we had hoped to lend. I felt as if we stood a world away, and although I wanted to step across and put my hand on the boy's shoulder, I could not make myself do it.

Soon Mike told us it was time to leave.

Guilt trip

As we neared the school, we could see some of the other children heading home with newly made nametags hung carefully around their necks. Many of the kids had poured the glitter we had given them on their faces and their heads, and several of the girls had painted their fingernails red with markers. They looked like a tribe of pygmy aliens.

One little girl sat next to Lindsey Peterson, an American, who majored in peace studies at Chapman University. Lindsey had dark hair and white skin. Her mother taught at a high school in inner city Baltimore. The little girl asked to be Lindsey's friend. Flattered, Lindsey agreed. The child immediately asked if it would be OK if Lindsey gave the child her watch. It was a very pretty watch, the little girl said. Lindsey looked at the child for a moment, and then in the most gentle voice she could achieve, told the child, "No." The watch was a gift, and she could not give it to her. Later Lindsey would tell me that she felt terrible not giving the child the watch because she has so much in her life. But Lindsey could not make herself give up the timepiece.

Once in our safe vans, we stuck out our hands to give the children a last few high-fives as we went. We pulled out of the gate and onto the top of the hill. We drove past the train tracks we passed on the way in and the yellow barbershop, and past the crowded apartments and shacks. In the distance we could see the green vineyards climbing up toward the base of Stellenbosch Mountain.

I thought about the children who feared me because they thought I was an American wrestler, about the wounded child I couldn't bring myself to help, about the watch Lindsey couldn't bring herself to part with.

I felt I had failed.

We'd all failed.

We drove home past all that South Africa is, and ended up right back where we started: the comfortable, white womb of the University of Stellenbosch.

Reach the writer at scott.buros@asu.edu.