Political candidates need money to successfully compete in an election, and in Arizona they have the choice to run for office using a public financing program to fund their campaign.

In 1998, voters passed the Citizens Clean Elections Act which was intended to promote participation in local politics and to fight political corruption, said Thomas Collins, the executive director of the Arizona Citizens Clean Elections Commission, which implements the act.

Arizona Sen. Juan Mendez, Rep. Athena Salman and candidate Melody Hernandez — the “Millennial Clean Team” — are all running together as publicly funded clean elections candidates for District 26, which represents Tempe. In District 26, Republican House candidate Seth "Marcus" Sifuentes is also a participating candidate. The district will be the only one in the state to have only public-funded candidates in office if three of the four candidates win the general election.

This year, out of over 100 candidates running for the state legislature, 25 are participating in the public-funding program, according to the Commission’s website. No other candidates in districts with ASU campuses — 16, 20 and 24 — are running clean, according to the website.

READ MORE: A 2020 Arizona general election voting guide for ASU’s campuses

Candidates using the program are referred to as “participating” on the Commission’s website and those not participating are using “traditional funding.”

To be able to qualify for the program, candidates must not accept special interest funding from political action committees or high dollar contributions from individuals, Collins said. Candidates must then receive $5 contributions from a certain number of registered voters in their districts or the state depending on the office they are running for, he said.

If candidates can meet those qualifications and qualify for a ballot, “there is a clean elections fund that will provide them a limited amount of money to spend on their campaign,” Collins said. According to the Commission’s website, legislative funds are distributed to qualifying candidates once they qualify for the primary election, and more funds are distributed at the start of the general election.

“The overall thrust of the act is to push corruption out by bringing people into the system,” Collins said.

Collins said over the course of the first decade of the program's resistance, multiple candidates ran successful campaigns using public funding. But changes over time have led to a decrease in participating candidates, he said.

In 2011, the program would change to allow fewer matching funds to participating candidates when their opponents using traditional funding raised more money. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision in Arizona Free Enterprise Club's Freedom Club PAC v. Bennett “that Arizona’s matching funds scheme substantially burdens protected political speech without serving a compelling state interest and therefore violates the First Amendment,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion.

Collins said the program saw a drop-off in participating candidates after that decision.

Participating candidates “don’t get to run a campaign with all the bells and whistles” due to the more limited funding, Collins said. But there are still some factors as to why a candidate might choose to run clean: They can connect with voters more than if they ran a traditional campaign, he said.

“I’m not a distracted candidate because of (participating in the program),” Salman, D-Tempe, said. She said money will always be a part of politics, but by not having to appeal to special interest groups or high-dollar donors, she can spend more time focused on her district and meeting the people she represents.

“When you run clean, you are reaffirming that your purpose, your mission, your goal as a public servant and as an elected official will be to serve the public good,” Salman said.

The focus of the program has always been about anti-corruption, “but there are other effects by democratizing the fundraising process,” Collins said.

The program has led to more women and diverse candidates running a successful campaign since the act was passed, Collins said.

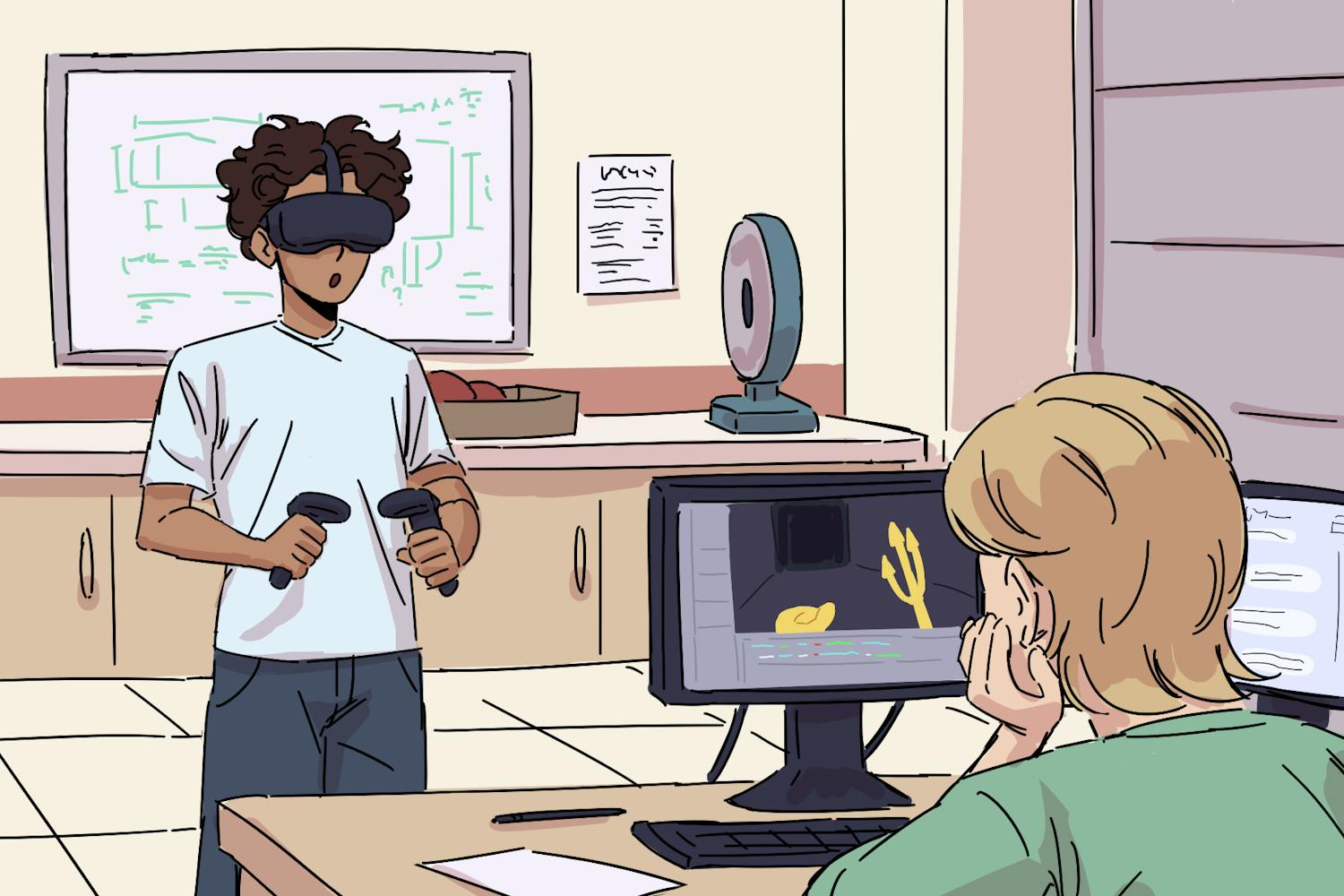

The act has also led to candidates with more extreme views running successful campaigns, said Matthew Dempsey, a faculty associate at ASU who teaches courses on interest groups and campaigns and elections.

“You just need to raise $5 from 200 people and you’re flush with cash,” Dempsey said. He said a traditional candidate would typically need to appeal to different groups and donors to fund their campaign. Now potential candidates who may not be able to get traditional funding due to their views can instead rely on the public financing program.

“It amplifies voices that in the past would have been almost stifled because they would never have raised any money,” Dempsey said. “That could be good, but it could also be dangerous.”

Reach the reporter at wmyskow@asu.edu and follow @wmyskow on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Wyatt Myskow is the project manager at The State Press, where he oversees enterprise stories for the publication. He also works at The Arizona Republic, where he covers the cities of Peoria and Surprise.