I first felt the sting of imposter syndrome at a college preparatory high school against a sea of white faces — a feeling I suppressed in an attempt to hold on to what was my promised ticket to a better life. To quote Claudia Rankine in her celebrated work Citizen: An American Lyric, "I feel the most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background."

Inspired after watching "Cidade de Deus" (or "City of God"), a film adaptation of the book by Paulo Lins, I picked up my first camera, determined to document my own community. Fast forward to my freshman year of college, I transferred to the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication in the spring. I felt like I needed to push myself and set myself apart, so I decided to join The State Press.

I needed to prove to myself that I could do this work, that I was actually deserving of the opportunities I had.

Part of this was survivor's guilt. My first semester was full of introspection and existential thoughts that threw me into a deep depression. Only a handful of the kids I grew up with were attending college; many others were joining the military, being sent to prison or entering the workforce.

Why was I one of the few? This question is one I ask myself even today.

I grew up with a stable family life, two parents and a sibling. We were low-income, but my dad made enough money to keep us from struggling. After the 2008 recession, times were tough but at least we were not homeless. We had the privilege of being documented, even though Senate Bill 1070 was a scary time for our community and the many who were deported. Southside Tucson felt like a ghost town.

I came to this industry with this perspective — a very lonely perspective.

But that does not mean I am alone.

"Journalists of color make up nearly a third of the full-time workforce among online-only news organizations," according to the 2019 diversity survey results produced by the News Leader Association. This is an upward trend in comparison to previous survey results that concluded only 17%, a "historic low." But what this data doesn't represent is inclusion; the act of bringing journalists of color into the newsroom is not enough.

"The lack of inclusion is a big part of the puzzle here," said Fernanda Santos, professor at the Cronkite school and former Phoenix bureau chief for the New York Times. Santos said the time for action is now and she is tired of hearing about change that is not paired with action.

"If diverse voices are not included in the journalism that we produce, how can we have an understanding of the importance of these voices?"

There are BIPOC journalists stepping onto the scene who have the same attitude as Santos. BIPOC journalists like Lerman Montoya, a graduate of the Cronkite School and Barrett, The Honors College. During his time at the Cronkite school, he focused on the vulnerable populations in which he existed.

Montoya grew up in Phoenix as a gay Chicano man with parents from Sinaloa. He was no stranger to the people he reported on; they were a part of his community.

"I always dreamed of being a journalist. Alongside his prison letters, my dad would send me outdated copies of National Geographic he found at the prison library," he said.

Montoya knew where his passions lay at the time and the trajectory he wanted to take in life. Those National Geographic photos allowed him to see past the concrete jungle and envision a life for himself that contrasted his surroundings.

Like many children of America's inner cities, he was told education would get him out of poverty. He was a good student, so he got into the honors program at ASU. As a child of immigrants, he had to figure it out on his own. Being low-income meant he had to figure it out fast. That "it" came in the form of journalism. During his time at ASU, he wrote stories about the LGBTQ+ community in Phoenix, hate crimes in Phoenix and told many more stories that lifted issues happening in the community into the news cycle.

"I wasn't some white girl from the suburbs reporting about immigration issues to get praise and notoriety for a story then move onto the next. I saw reporting as a service to my community. I remained involved. I memorized their names, their stories, their interests," Montoya added. "My family's complicated relationship with immigration kept me grounded in the work that I was doing."

In his time reporting at Cronkite, Montoya saw positive impacts in the communities he covered, but often faced challenges getting his ideas approved.

"I believe that my work was valued for Cronkite News. I was passionate about what I reported on and it could be clearly seen. Though some people questioned my intuition or ideas, I was always trying to highlight marginalized voices in a typically conservative space," he said. He echoed a sentiment shared by many other students from marginalized communities, specifically in reference to the Cronkite School's objectivity policies.

"They preach objectivity to the point that sometimes it feels like having to walk a fine line of calling something out for what it is and remaining objective but losing a lot of the important context," he said. He believes these guidelines ultimately prefaced his transition out of the field. I have heard this story many times in my three years at Cronkite: frustrated students feel they must erase their identities to be competitive candidates in the field.

Santos said this lack of representation is not a problem specific to the journalism industry. "People of color and people from marginalized communities have been pushed out of many professions, many careers because of the fact that they have felt unseen, unheard, disrespected and misunderstood," she said.

The semester I joined The State Press community desk, I was under the leadership of Joseph Perez and Adrienne Dunn, the current magazine editor-in-chief and executive editor. I told myself I would focus on the student populations I felt were not being provided a platform — those who were vulnerable. I would interview Latine students, Black students, low-income students — people for whom I could provide a safe space to share their stories. The first story I planned, sourced and drafted surrounded a Trump administration decision on a state of emergency to pass a budget for the border wall. I felt there was a lack of humanity involved. I chose to write a story titled "How does the state of emergency affect undocumented and DACA students?" If you look that story up on The State Press website, you won't find it.

I interviewed several undocumented students and others enrolled in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. Their voices and experiences were important to me. Oftentimes, we get lost in the policies and forget they have real-world consequences.

In order to honor those experiences, I offered anonymity to a source to provide a space for his opinions without fear of being targeted by ICE. Keeping this student's identity under wraps proved to be an issue, though my desk editors understood where I was coming from. Once the situation was brought to editors in higher positions I ran into a wall; they felt there was no immediate danger to the student.

I had grown up with mixed status families so I understood the fear of being exposed as undocumented. The current "zero-tolerance" policies made me uneasy, and due to how unpredictable the Trump administration's policies on DACA and undocumented students had been, I stuck to my gut feeling.

In the end, the story was never published. I was upset. The perspectives of these students were never brought to light.

Why was there no space for these perspectives? Was this student's name more valuable than what they had to say? Does this happen often? Do I really want to keep doing this?

I felt journalism had turned its back on vulnerable people, had turned its back on a community already left out of the conversation, and had turned its back on me.

This reflects the issue of the weight of inclusion in a newsroom. So what does inclusion look like? Inclusion looks to me like the work journalists of color have been producing such as "The 1619 Project" at The New York Times, or "Chicano Moratorium at 50" at The Los Angeles Times. These are projects that push the envelope on the roles BIPOC journalists play in the newsroom.

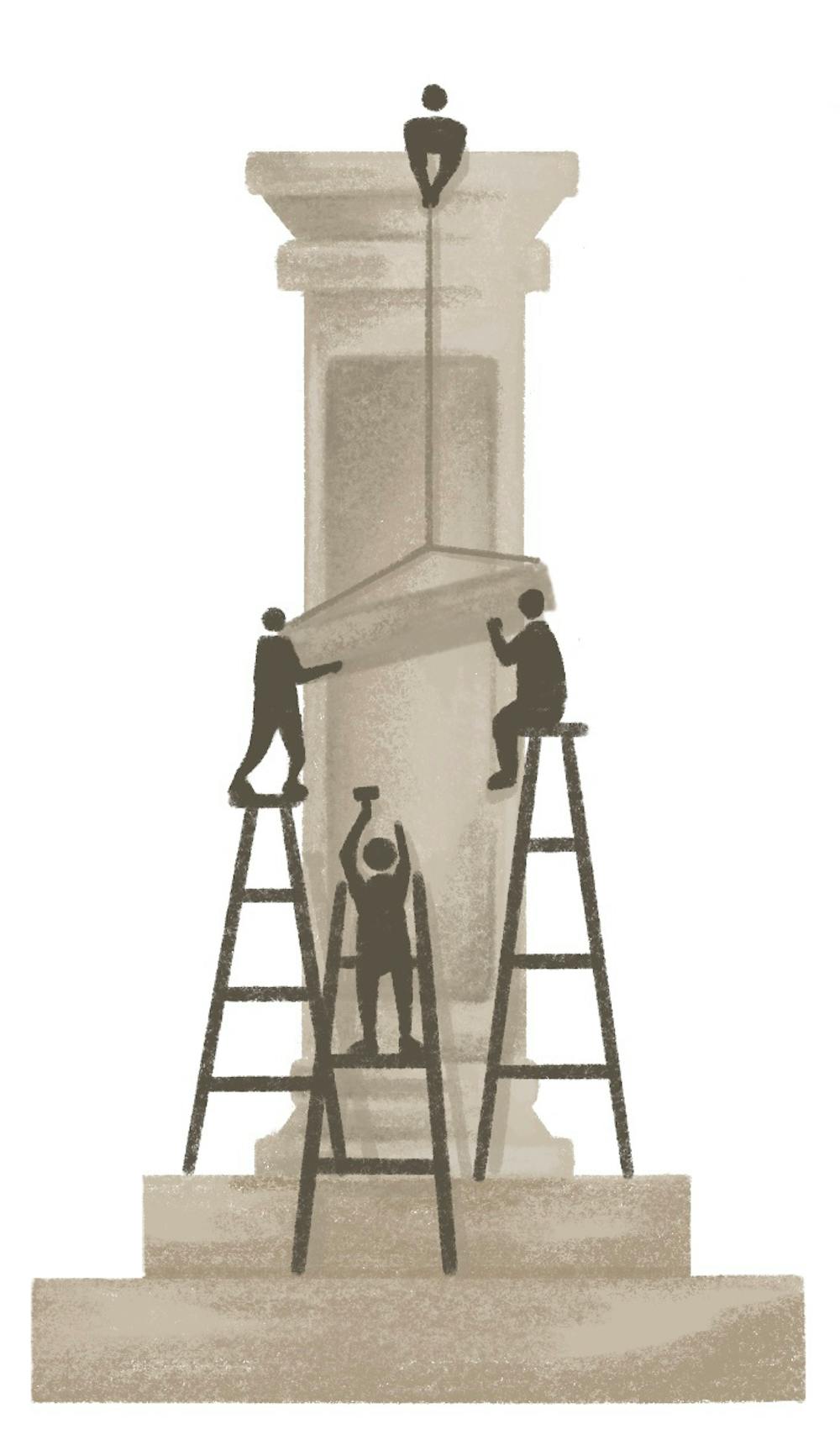

The industry has made strides in deconstructing the tokenization and silencing of BIPOC journalists, especially over this past summer. With racial unrest at the forefront of news cycles, more people began to discuss the role of journalists of color in newsrooms across the nation.

Santos believes we need to begin discussing where to go from here. "I feel that I'm listened to, that I'm heard, that my perspective is valued by the people who are genuinely interested in changing things more than ever in my 22 years of journalism in this country," she said.

As Santos put it, "the very survival of journalism depends on journalists who reflect the many communities that journalists cover."

Empower the journalists of color in your newsroom. Now more than ever.

Reach the columnist at rjromer8@asu.edu or follow @RaphaDeLaG on Twitter.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.