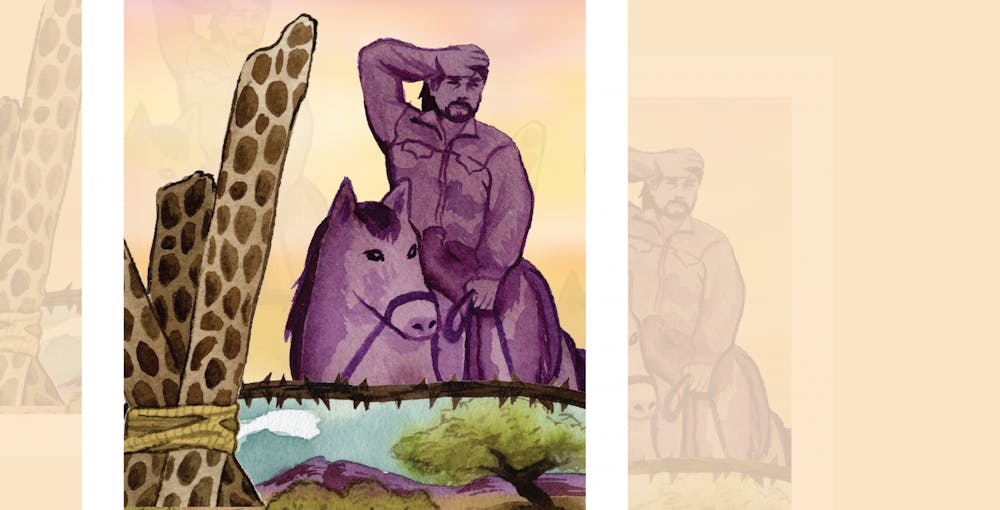

Jesus wiped the sweat off his brow as he kicked his stolen horse. It's 1905 and they’re about to cross the Rio Grande River.

The banditos he left behind are probably realizing something is wrong by now, but he's hours ahead of them, and once he crosses the river, they’ll never find him.

He took a breath, felt the horse underneath him tense, and in one moment of truth, one final leap of faith, he heard the roar of the river behind them. Safety.

Jesus grew up in a village somewhere in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Slowing down, looking back at the life he left behind, he signaled his horse to keep going. At 15 years old, he had the rest of his life ahead of him.

In 1905, my great grandpa found a ranch in what today is considered Beeville, Texas. He met with the rancher who agreed to shelter him and let him work for his dinner, in exchange for the horse.

Jesus would later marry the rancher’s daughter, move to Brownsville and start a family. They would strive toward achieving the American Dream while also keeping in touch with their roots. Jesus lived to be 101 years old.

Now, forget about Jesus. Let's talk about the rancher, my great-great grandfather.

This ranch was well-established, and had been in the family for at least a generation. My great-great grandfather inherited it from his father, which puts the ranch, at its youngest, at 115 years old.

This man, and the rest of his family, had never moved from that spot as far as we know today. Which means he never crossed any border, unlike Jesus. For my ranchero ancestors, the border moved around them. They've always been true Tejanos.

Texans of Mexican descent – descendants of Spaniards and Mestizos – are a people who have been in the same area of North America for generations. From Native Mexicans, to proud Texans, to everyday U.S. citizens, Tejanos are their own subculture under the Hispanic umbrella.

Tejanos were vaqueros (what most people recognize as cowboys), and with the job came a blend of music, food and values. Our music features an accordion instead of a tuba, and our legendary singer is Selena Quintanilla instead of Mexico's beloved Vicente Fernandez.

Tejano food, or Tex-Mex, is known for using more meat and cheese than typical Mexican dishes, with cattle products being the most common (barbacoa, carne asada, fajitas, etc.).

Professor Irasema Coronado is an expert on human rights on the U.S.-Mexico border, currently director and professor of ASU’s School of Transborder Studies.

"Tejanos have their own music, their own dance, their own history, their own culture, their own language," Coronado said. "It's a very old, rooted culture in that part of Texas."

Today, it’s hard to put a number on just how many Tejanos are currently in Texas, as Tejanos are formally defined as Texan residents of Mexican descent. Census data will give plenty of statistics on Hispanic and Latine residents of Texas, but not Tejanos.

Professor Carlos Vélez-Ibáñez, currently Regents' Professor of the School of Transborder Studies and School of Human Evolution and Social Change, said the history of South Texas is complicated due to generations of revolutions, land grabbing and countless immigrant groups coming to the state from the east and south borders.

According to Vélez-Ibáñez, it only takes one generation to become Tejano. "You can rest assured that Texans of Latino or Hispanic descent are most likely Tejanos," he said.

Hispanics made up 83.8% of the population in South Texas according to the 2019 state population estimate.

Not all Tejanos describe themselves as such, and not all Tejanos know of their ancestry and generational line attached to the state of Texas thanks to violence, systemic racism and generations of conflicts and contradictions. But the people are there, the culture is there, and the struggles are still there. Some of them may not be in Texas anymore, but their roots are still Tejano.

"There's a whole cultural package that goes with being a Tejano," Coronado said. "Not everyone has the same experience, but it's important to know that there's this unique and special culture in South Texas — its history, its music, its folklore ... it’s a special place."

The No. 1 trait I’ve seen in every single one of my Tejano family members, and frankly, in myself, is an unrelenting pride and stubbornness for what they believe is theirs, what they believe is true and what they believe is right.

For my family, being Tejano is a source of pride, and Tejanos living in Texas right now, living in the same place they’ve lived in for generations continue to strengthen their identities.

Many Tejanos living in Texas during the 1800s never crossed a border, much like my own great-great grandfather. Instead, the border moved around them over time.

Texas had been part of Mexico up until Texas declared itself an independent nation in the mid-1830s. Texas was annexed by the United States in 1845, an annexation recognized by Mexico only after the conclusion of the Mexican-American war three years later, with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Then, in the 1860s, Texas declared its secession from the U.S. to join the Confederacy.

Even with this timeline, the Texas-Mexican border has always been fuzzy.

"El valle has always been a center of conflict," Vélez-Ibáñez said. "South Texas has been a mural of conflict."

Both Coronado and Vélez-Ibáñez mentioned the infamous 19th century Texas Rangers, who were known to be notoriously violent and brutal in their treatment of Hispanics and Latines in South Texas.

Vélez-Ibáñez recounted the history of the Texas-Mexico border, or lack thereof, calling it "insignificant" for many decades. From a river, to a yellow line, to a road, to a chain-link fence, Vélez-Ibáñez said there was hardly any difference between places like Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora. In South Texas, the differences were even smaller.

Additionally, Border Patrol, as we know it today, was only established in the early 1920's as a result of the Immigration Act of 1917, the second law after the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to restrict immigrants from entering the U.S. along the Mexican border. The 1882 act was the first time a type of U.S. immigrant was considered "illegal."

Ultimately, it wasn't unusual for Jesus to have crossed into the country the way that he did, and it was even more common for men like my great-great grandfather, the rancher who took him in, to say he was from Texas. The tight border security Americans are used to in the present is considerably new.

Now, when people ask members of my family where we’re from, the following conversation ensues:

"Where are you from?"

"Texas."

"No, but where is your family from?"

"Texas."

"But before Texas?"

"We've pretty much always been in Texas."

For as long as I can remember, I've heard stories of my family. From my great-great grandfather always being here, to my great-grandfather creating a life in Brownsville, to my grandfather serving in Vietnam and earning a Purple Heart.

My family has been a part of this country’s history since quite possibly the beginning. And yet, my family has struggled well into the present day.

After returning from Vietnam, Jesus Jr. wasn’t able to get assistance for his PTSD, given the lack of a Veterans Affairs hospital in South Texas until 2009. The machismo which ran alongside Tejanos certainly didn’t help him get diagnosed either.

Machismo culture is a pattern among Hispanic and Latine men who exhibit exaggerated masculinity, often taking pride in the outdated ideal of "being manly." One of the biggest setbacks of machismo culture is the discouragement of men to feel their own emotions, or seek help for mental and physical health issues.

Their luck continued to fall. Suddenly, my family found themselves living in the projects, and mine isn’t the only one.

Dating back to the early 19th century, Coronado said Anglos in the area were able to take advantage of Mexicans with property taxes and new business practices they were unknowingly imposed with, causing them to lose investments

"They started to lose ranches and assets and resources that they had, and then we became an underclass," she said.

Today, systemic oppression in the region can be traced back to roots of a constantly conflicting population. "Low income, no health insurance, very little resources, very few institutions of higher learning, so the opportunities for upward mobility are limited," Coronado said.

Thousands of Tejanos experience a particular struggle in the U.S., with prejudice, patriotism, machismo, pride and an unrelenting stubbornness. Tejanos have faced challenges in reaching the American Dream even though plenty of them have been Americans for generations.

"We call them projects because they're government housing. But they're literally a housing project, as in, a project to keep low-income people housed," my dad once said. "When I lived there, my whole day was consumed with, 'How do I get out of here?'"

Approximately 23% of Hispanic residents of Texas live below the poverty line, with Hispanic residents making up approximately 38.2% of the population in the state. Counties which cover South Texas are among the poorest counties in the state, with high Hispanic populations.

"Any opportunities for upward mobility are limited because you have to leave where you are from if you're going to get a degree or some form of higher educational experience," Coronado said. "You don't pass on generational wealth because you don’t have any."

But getting out of poverty didn’t help my dad avoid prejudice. More than once, he would come home from work exhausted, on the phone with a friend or colleague, venting about how he heard the dreaded phrase again that day, "Oh, not you though. You're not like them."

It’s a far cry from, "Go back to your country," but still full of hate. We are Mexican, we are Tejanos, and this is our country. We, along with an unknown multitude of Tejanos, have always been here.

"Mexico never left," Vélez-Ibáñez said. "It just became English-speaking."

Reach the reporter at jjcabre1@asu.edu and follow @joyce_cabreraAZ on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.