Known to the world as the First Nations, Indigenous populations have spanned the historical timeline, maintaining their sense of culture and indigeneity despite centuries of loss and oppression.

Indigenous peoples make up less than 2% of the total American population, and as time goes on, many are finding ways to preserve or reclaim the stories of their ancestors.

One driving force behind this celebration of culture is art, which is evident through Indigenous artists at ASU putting their identity into their storytelling, illustrations or architecture.

Lucilla Taryole, a junior studying animation whose artwork has a “modern take,” agreed that art can be used to represent Indigenous culture, as well as to preserve cultural roots and adapt to new forms of expression.

“It’s creative visibility,” they said. “Indigenous artwork doesn’t always have to be a (specific) artwork. It can be different and doesn’t always have to be the same thing.”

Taryole, who is Kiowa and Mvskoke, works for ASU’s Center for Indian Education and Labriola National American Indian Data Center, which have provided them with experience and connections within the University’s Indigenous network.

At the Center for Indian Education, Taryole is surrounded by graduate students, professional scholars and school offices who ask if they can create art for various research projects and events.

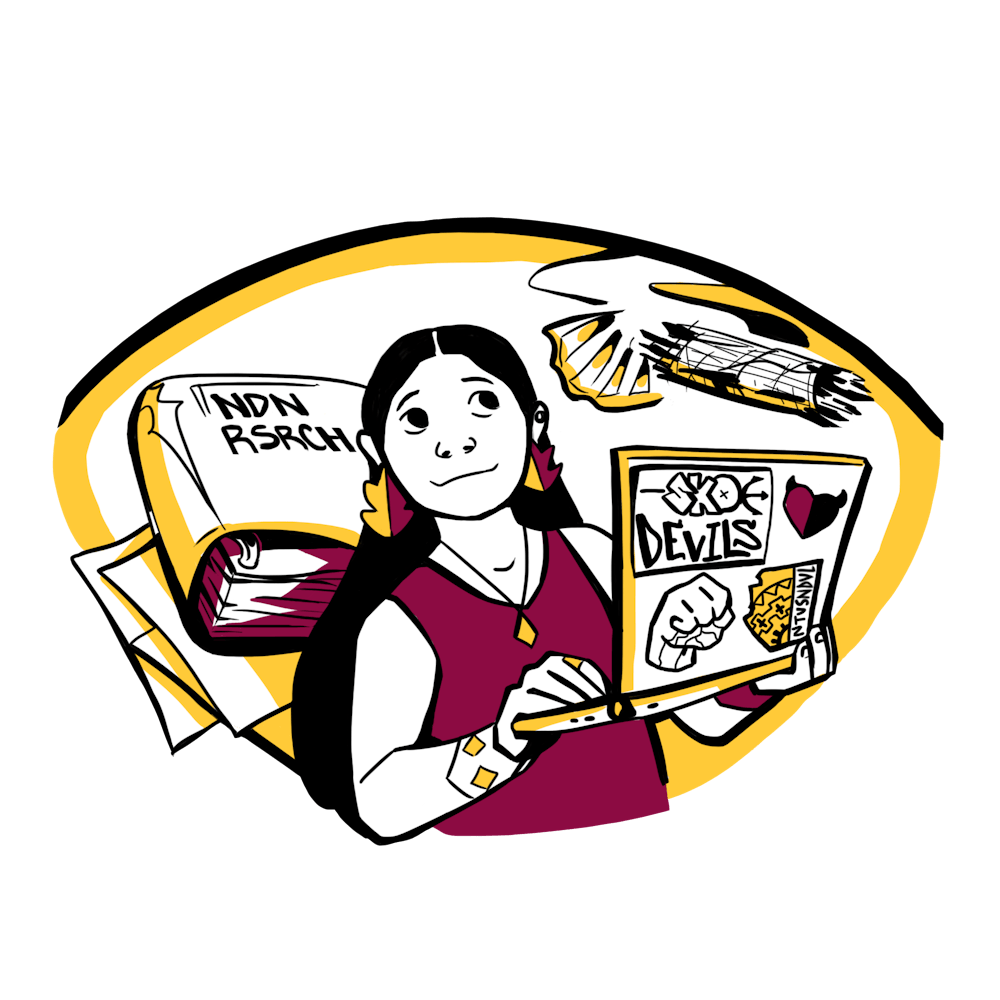

Inspired by Taryole’s youthful, cartoonish art style, the University’s Office of American Indian Initiatives commissioned them to create a graphic for the Doing Research in Indigenous Communities Conference, which it co-hosted at the Tempe campus in October. With Taryole’s graphic, the office aimed to show Indigenous students that graduate school is not always intimidating, but rather, can be fun and fulfilling.

“The main point was to create a visual representation of an Indigenous student,” they said.

To accomplish this, Taryole said they drew an Indigenous student with “a face that people know is Native,” long hair and Kiowa oak leaf earrings. Accompanying the student were research materials, like a laptop and binder.

Beyond the conference, Taryole and their design were also featured in a Q&A published by Turning Points Magazine, an ASU publication for Indigenous students.

No matter how modern or nontraditional their work may be, Taryole aims to dedicate their art to their Indigenous culture, such as their work “Shifting the Narrative,” a collection of illustrations showcasing Indigenous actresses Lily Gladstone and Paulina Alexis.

“It’s not traditional, but it still has a heavy tie to Indigenous presence,” Taryole said. “I would like my artwork to encourage other young Indigenous artists to know that they’re not confined to certain mediums of art.”

Language reclamation and political statements

“I’ve always felt a connection to land when writing, knowing that it is a very ancestral practice of not being separated and seeing land as one of us,” said Ayling Dominguez, an Indigenous poet, visual artist and graduate student studying creative writing.

Dominguez comes from the Nahua people of Mexico, and they also have roots in the Mexican state of Puebla and the city of Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic.

Through their writing, Dominguez accomplishes the work of language reclamation, a task that Indigenous peoples are constantly doing for the many Indigenous languages that are considered endangered, they said.

Dominguez said that through poetry, they are given room to feel their emotions — something “rigid” academic spaces kept them from doing. Dominguez’s work centers around historical and familial archives, and they are trying to “push” the boundaries of English and “colonial language.”

“How can I experiment with the language and push the language a bit further to account for the experiences of being in the Indigenous diaspora and the experience that perhaps the original language didn’t account for?” Dominguez said.

In their work, they often reimagine cultural legends and myths, especially ones featuring female characters.

“The story is told from the point of view of a male or a character who is viewing that character without getting her full personality,” Dominguez said, describing how they write their poems.

In one of the classes they took, they were expected to write one poem per week, which pushed the boundaries of what Dominguez was used to. In the end, however, it helped their growth as a writer.

“A lot of times, I start with images in my mind and memories, especially trying to see what memories I want to make sure I never forget and are never forgotten, especially because so many Indigenous histories have been taken over in American history,” Dominguez said.

One of the main obstacles they face as a poet is the cultural barrier from their peers — not being able to give feedback or feedback not being given through a cultural lens.

Beyond Dominguez’s poems, their artwork has been featured in ASU’s Grant Street Studios and the Phoenix Art Museum. One piece, titled “Bad Seeds,” was created by smashing and rearranging a police barricade and scattering dirt around the broken pieces, a commentary on police violence.

“People will say (a police officer) was just a bad seed,” Dominguez said. “In reality, in my opinion, and the community I come from, there are no good police. There are no bad seeds when the whole system is rotten.”

Collage art is another way they express their indigeneity. Dominguez came to the practice not thinking it would be “serious” artwork. However, once they started, they realized the work aligned with their values of building a better world. Dominguez starts their collage art process by flipping through a magazine to see what images speak to them, looking for double meanings that they can reconfigure as statements in their art.

“You’re literally taking something that exists and you’re cutting, reconfiguring it, restructuring it to make something else out of the existing, which I think is a very political statement,” they said.

The placekeeping framework

Wanda Dalla Costa was in her 20s when she went on a backpacking journey that was “never supposed to be more than six months overseas.” However, she still found herself backpacking around the world by herself seven years and 37 countries later.

Through her travels, she witnessed many Indigenous people practice aspects of their ancestral culture and have close ties to their native land. After her adventure finally came to an end, she returned to North America and realized they were living “in these little boxes that are completely detached from (Western) culture.”

“We are detached from all the beautiful systems that exist within our culture,” Dalla Costa said. “If people overseas and all these cultures around the world can still stay connected to their built environments through architecture, planning and landscaping, why can’t people on the mainland remain connected?”

Dalla Costa is a member of the Saddle Lake First Nation and the director of ASU’s Indigenous Design Collaborative, which aims with its projects to “increase authenticity in the field of design.” The collaborative started “informally” after Dalla Costa taught a theory course and it became more formalized over the years. IDC received positive responses from students, faculty and tribal community members.

“I guess (students’) knowledge of local cultural history is very limited,” Dalla Costa said. “I think the students appreciate the firsthand learning when you walk into an Indigenous community, and you can talk firsthand with people through their voices and a firsthand method of understanding. It becomes much more impactful than learning from a book.”

“It begins cross-cultural communication between non-Indigenous people and Indigenous people through these artifacts,” Dalla Costa said.

When she began at ASU in 2016, she saw an opportunity for students to work directly with tribal communities in an applied learning model, “Teaching Indigeneity in Architecture: Indigenous Placekeeping Framework.” The framework comes from her practice, Tawaw Architecture Collective, and has been developed over the last 30 years.

“We developed this framework when we work in a community because the way I was taught architecture integrates local community perspectives,” she said.

Dalla Costa said architects’ knowledge is limited because the way architecture is made can be “disconnected from the people, their history, norms, aspirations, culture and philosophies.”

“It’s completely devoid of all of that because architects are not taught how to work inside their community.”

Some of the IDC projects featured in ASU’s Hayden Library focused on “indigenizing ASU’s campus through design.” IDC’s Hayden Library Welcome Wall was a greeting wall aimed at creating awareness of Arizona’s Indigenous languages and welcoming Indigenous students to the Tempe campus. The design, which is driven by land recognition, language and the empowerment of Indigenous artists, and it aims to honor the 22 tribes located in Arizona and features 19 words from shared ancestral languages.

Another IDC design in Hayden Library is the Hayden Library Labriola Custom Table, a collaboration with a local Salt River Pima-Maricopa Community metal artist, Jeffrey Fulwilder, who brought his own lived experiences to provide perspective on the design. The design comes from the local O’odham tribes' ancestral tradition of basketry designs, which derive from desert lifeways and materials.

“We wanted to do a metal piece to commemorate (Fulwilder’s) work, but we needed an authentic narrative,” Dalla Costa said. “We sat with Jeffrey for many meetings, and he ended up sketching out a basketry design, a series of baskets that, of course, have embedded meaning.”

Taryole emphasizes the importance of Indigenous artists, including a contemporary influence on their work to represent the perseverance of Indigenous cultures in the modern age.

“We’re still alive,” Taryole said. “We’re still making moves where we’re constantly at work. We’re all different, and we’re still here.”

Edited by Camila Pedrosa, Savannah Dagupion and Madeline Nguyen.

Reach the reporter at fgabir@asu.edu and follow @FatimaGabir on X.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook, follow @statepressmag on X and Instagram and read our releases on Issuu.

Fatima is a junior studying journalism and mass communication with a minor in justice studies. This is her fourth semester with The State Press. She has also worked at Phoenix Magazine.