Listen to the article:

Sophie Stern wants to major in dance and join a sorority at ASU. She grew up close to the Tempe campus and knew she wanted to attend the University from a young age. Now, after two years of community college, she wants a traditional college experience — attending classes, living on campus and going out with friends. But the odds of her being accepted by the University aren't high.

Stern has Down syndrome, a genetic condition caused by the presence of an extra copy of chromosome 21. ASU has a short, but restricting in Stern's case, list of qualifications for admittance that requires applicants to have one of the following: being in the top 25% of your high school graduating class, a 3.0 GPA in competency courses, an ACT score of 22 (24 for nonresidents) or an SAT score of 1120 (1180 for nonresidents).

Those with Down syndrome often have intellectual disabilities, which can make standardized testing and maintaining a qualifying GPA difficult. Unlike other universities, ASU does not offer a specialized path for students with Down syndrome or other intellectual disabilities.

Stern is currently considering universities with programs for students with disabilities like Down syndrome. "My dream program would have a theater company, mostly to dance. I would be able to live in a dorm with a roommate, and I would have someone to walk with me to class and help with my homework and courses," Stern said.

Currently, ASU has no diversity, equity and inclusion goals and did away with affirmative action in 2002 when Michael Crow became the University's president. Crow's definition of inclusivity is admitting every qualified student.

"It's bullshit," Stern said. "We need [the University] to open up for other people who have a disability. ... I want a college experience at a university that has a program for people with disabilities."

The ASU charter states that the University measures itself "not by whom it excludes, but by whom it includes and how they succeed." However, current and prospective ASU students with disabilities have found that this does not align with their experiences at the University.

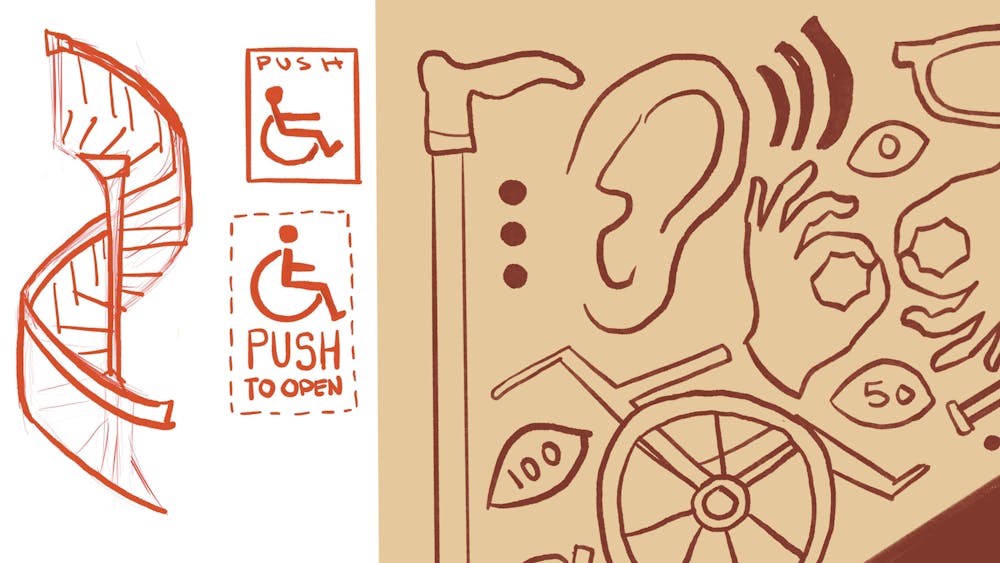

Barriers to entry, lack of privacy, accessibility issues on campus and fear about changing DEI policies means students with disabilities at ASU must go to extra lengths to advocate for themselves and ensure their success.

Access to accommodations

Katie Allee, a second-year law student who has cerebral palsy, made an appointment with ASU's Student Accessibility and Inclusive Learning Services to sort out her accommodations several months before starting school at ASU.

"I wanted to know everything I needed to prepare to be a student here, and in that meeting, I felt like I knew everything I needed to and I was good to go," she said.

But when the fall semester started, Allee realized she wasn't prepared enough when it came to understanding the requirements for requesting accommodations at the University.

"I was starting school and going to orientation, and on top of that, I was needing to understand the accommodation process of SAILS," Allee said. "I felt like it was a lot at once, and even then, I was still confused about how the [SAILS website] portal works and who to reach out to for different needs."

Having completed her undergraduate degree at Montana State University, Allee was surprised by how different the accommodation process was at ASU, as she felt like her previous school's process was more accessible.

"There was an office with Disability Services, and I was able to just email them when anything came up," Allee said. "They were pretty diligent about responding fairly quickly. ... The director had given me their personal phone number, which was really nice to just reach out when anything came up."

Cerebral palsy is a group of conditions that affect movement and coordination caused by damage to the developing brain, most often before birth. As a result, Allee relies on note takers, accessible classrooms, flexible assignment deadlines and test-taking accommodations in order to succeed as a student.

One of the University policies listed in its Academic Affairs Manual states that the University will make "a good faith effort" to provide reasonable accommodation for qualified applicants, employees, students and members of the public with a disability unless the accommodation request would cause an undue hardship as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

These specific needs are made clear to professors before the semester starts and are anonymous to protect student confidentiality — but according to Allee, some faculty members veer from this practice inside the classroom.

"I serve as the president of the Disabled Law Students Association, so I've had some peers come to me," Allee said. "It sounds like there's concern about professors speaking about students' accommodations in front of other students, and things that should remain confidential but aren't, because professors don’t realize that it's personal information."

Like all students' privacy, disabled documentation is protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, which, according to the SAILS website, prohibits the sharing of students' disability-related information without their consent.

Without anonymity, Allee said her disability might overshadow her hard work as a law student.

"A lot of students prefer [anonymity] because in law school, there's a lot of social networking aspects that aren't in place in other schools," Allee said. "Professors can recommend you for jobs. ... It's important for students to be measured [by] their abilities rather than their disabilities."

Another major topic among students in DLSA is the law building's lack of accessibility.

"We have push button accessibility doors, but the buttons don't work in a lot of the places," Allee said. "It's funny because we're in a pretty new building, [but] we've had issues where buttons don't work for years at a time, so we've been trying to lobby to get that address[ed] through our administration."

Despite their advocacy, Allee and other law students with disabilities are still unable to resolve the issue.

"Our dean of diversity has been working with us for at least the last two years, and she's very diligent about meeting with us and giving us updates," Allee said. "It seems to me that she's doing her best to take the issue higher [up], but [we keep] getting the same answer that we can't get money for it to be fixed."

Learning gaps

When people ask Alex Rank, a junior studying psychology who has cerebral palsy, why they decided to minor in disability studies, they joke and say it's because they were bored.

Disability studies was added to the ASU course catalog in 2019. The field of study has grown in recent years and the degree seeks to provide students with a multifaceted understanding of the social, cultural, political and economic dimensions of disability.

Upon starting their disability studies minor, Rank was surprised by the sheer amount of things their fellow students didn't know about people with disabilities.

"I purposely insert myself into the [disabled] community, and we all kind of know what's up; then I get into these classes and it's like, wow, people don't know anything," Rank said. "People don't understand that people in wheelchairs consider their wheelchair to be part of their personal space, which is mind blowing to me. Also petting people's service dogs and other basic stuff like that."

Although disability studies has been at ASU for six years, the majority of the professors teaching the courses have backgrounds in other fields and are not specialized in disability studies. While this program is still relatively new to the University, the lack of expertise in an area of study focusing on the largest minority group in the United States has raised concerns.

"A lot of the professors who teach disability studies ... don't have any sort of direct experience with disability studies," said Jessica Lopez, a junior studying business online with a minor in disability studies who was born without hands and feet. "That was kind of disappointing. They're not going to be teaching it in quite the right way if they haven't at least studied it or have that lived experience."

Although most professors may not have a disability or traditional background in the field, Rank said their professors are up front about it. Another criticism of the major is that it is only offered through ASU Online and ASU Sync, and only some classes are offered in person on the West Valley campus.

"ASU is decentralized," said Sarah Bolmarcich, an instructor in the School of International Letters and Cultures who has an inherited hearing loss condition. "I take classes even though I'm a faculty member, and I have been in a couple of the online disability studies courses at the [West Valley] campus.

"What they do is take a very sociological approach to disability studies. But it's far richer than that. For instance, there's significant work in disability studies in the humanities, and I think there would be another benefit of sort of [expanding the major] to other campuses."

Having the disability studies program on other ASU campuses would increase visibility and access to the field of study, which could improve ASU's inclusivity culture, Bolmarcich said.

While the program has been subject to criticism, Rank and other students benefited from sharing their experiences with classmates.

"I'm really glad that it exists, but it's also kind of frustrating because I know this — it's my experience," Rank said. "All my experience has bled [into my work] because I can't turn off my disability, so it's in everything."

DEI and the future

As ASU has started to quietly change its DEI language across the University, students with disabilities have shared their fears for the future.

"I'm worried that now it's going to [mean] working four times as hard just to get a job and make [employers] see past very trivial things," said Catherine Novotny, a third-year law student who is deaf and hard of hearing.

Novotny relies on accommodations to succeed in her classes, including preferential seating, early access to PowerPoint slides and an ASL interpreter.

"I worry that [the University] is going to see the expense of an interpreter as too expensive, and if the DEI changes mean anything, they're not going to be as worried about the legal ramifications of not providing accommodations that I'll need," Novotny said.

While the University's DEI policies have not directly affected her daily accommodations, Novotny has already experienced losing access to them in her studies.

"I took [an exam] last year and they denied my request for an ASL interpreter because the exam did not have any audio or visual component, even though I rightfully pointed out that there's proctors for the exam," Novotny said. "I'm in the process of applying [for] the bar right now. ... I'm really scared that they're not going to give me an interpreter this time, so I've just provided so much documentation."

The executive order signed by President Donald Trump in January says "many corporations and universities use DEI as an excuse for biased and unlawful employment practices," and "threaten the safety of American men, women, and children across the Nation by diminishing the importance of individual merit, aptitude, hard work and determination." But according to Novotny, this couldn't be further from the truth.

"I don't think I would have succeeded in my academic career, personally or professionally, without some form of DEI," Novotny said. "It allows people to see that not only am I qualified for the job, but I can be the best person for their job."

Although the future of DEI at the University remains unclear, Novotny said the most important thing for students with disabilities to do is to continue defending their autonomy.

"Something mentioned in my old [individualized education program] was working on self-advocacy," Novotny said. "Schooling is where you become a full-fledged, rounded person. And [it] really supported me through becoming who I am today."

Edited by Savannah Dagupion, Leah Mesquita and Audrey Eagerton.

This story is part of The Best of ASU, which was released on April 30, 2025. See the entire publication here.

Reach the reporters at aeagerto@asu.edu and lmesqui2@asu.edu and follow @leahmesquitaa on X.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook, follow @statepressmag on X and Instagram and read our releases on Issuu.

Audrey is a senior studying journalism and mass communication. This is her fifth semester with The State Press. She has also worked at The Arizona Republic.