One thing I have always been protective of has been my voice when I write. I admit, when AI boomed a couple years back, I was curious of what using it to speed up a writing process would look like.

I tested it out to help with sourcing, and though it gave me ideas I hadn't thought of, it also came with a refined outline for how I should write. That's when I took a step back, because although AI's ideas were polished, it wasn't me — I'm not even someone who works off outlines.

I was reminded of this when I learned that Stephen King doesn't even remember writing "Cujo," because he was under the influence of cocaine, which he shared he used.

"There's one novel, Cujo, that I barely remember writing at all," King wrote in "On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft." "I don't say that with pride or shame, only with a vague sense of sorrow and loss. I like that book. I wish I could remember enjoying the good parts as I put them down on the page."

This struck me because, instead of celebrating the success "Cujo" achieved, King was left with a sense of disconnection from his own work, missing out on the relationship a writer has with his draft as it takes form.

About 44 years later, the form of shortcuts have changed. Now, for some writers, that shortcut is AI, which, similar to the substances King relied on, offers speed and fast ideation.

"I actually think cocaine is a really good analogy for AI," said Andrew Hudson, a graduate student in creative writing and a speculative fiction writer. "If you look at how universities and institutions talk about AI, it does feel like you could swap the word cocaine, and you would have a clearer picture of what's actually going on."

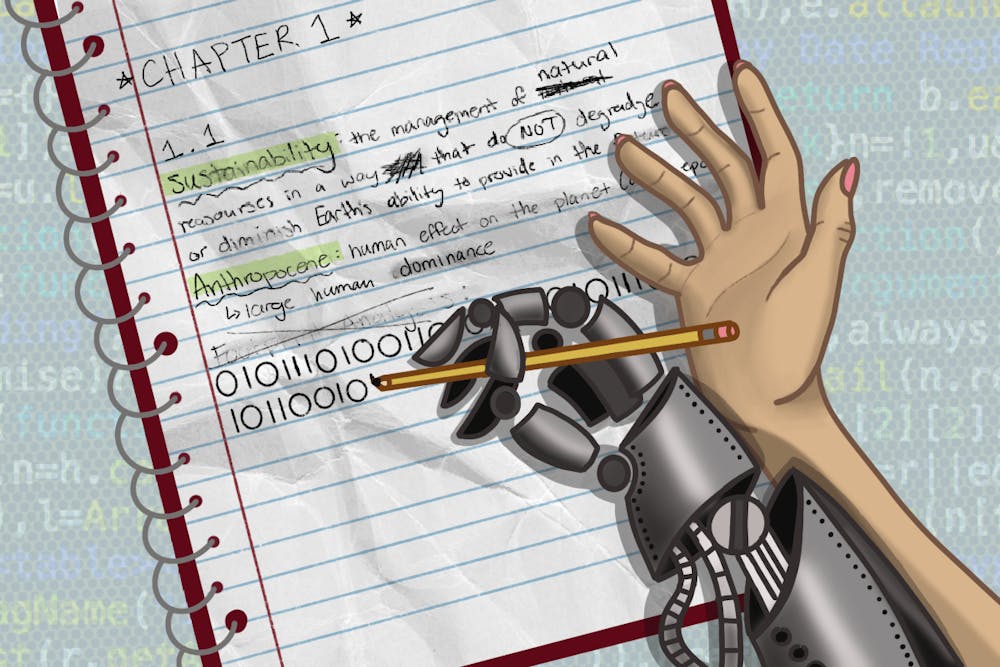

Just like King's use of cocaine left him feeling disassociated from "Cujo," AI carries the same risk of alienating writers from their own pens. That feeling of disconnect is what I feared — feeling no connection and not being able to see myself reflected back. When it comes down to it, AI is a system designed to provide "refined," filtered and grammatically perfect writing.

Although the end product is what a writer works toward, this does not make the creative process any less important, with the messy drafts, run-on sentences, the revisions — all imperfect parts that help curate a writer's voice over time.

Without the multiple drafts in disarray, replaced by a ChatGPT polish, I fear I could lose the heart of my voice: my awkward phrasing and peculiar diction.

Writing Center tutor and creative writer Chowdhury Noor Abrar Ahmed Siddiky said while AI can be useful when it comes to researching, relying too much on it risks weakening one's craft.

"This is something that I was actually thinking some while ago," Siddiky said. "If I just put something in ChatGPT, and it rephrases and makes everything for me, at that point, I lose the capability of making words or sentence structures that come up from my mind ... if I use it too much, it's taking all of my creativity."

READ MORE: Human vs. artificial art: The people, laws, tools working against AI exploitation

The struggle between a polished machine's output and the imperfect but authentic words of a human is not a modern dilemma. It has been expressed in fiction for decades.

In fact, Hudson mentioned Frank Herbert's "Dune," a literary work that takes place in a world where society bans thinking machines after a war with AI.

"Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind," Hudson quoted from Dune, reflecting a creed that is lived by in the book's universe.

"To the extent that we make these ... machines that are either simulating human creative acts or are pretending towards being human in the form of chatbots," Hudson said. "Those are the ones that I feel like are really nasty for our society."

READ MORE: 'Dune: Part Two' messages and themes are far from fictional

It is in raw experiences where the magic of human writing shines. When reading one of J.R.R. Tolkien's books, Siddiky was able to truly visualize the setting in the way Tolkien meant.

"That made me feel like, 'How can someone write so well that I can find visuals of that thing right in front of me?'" Siddiky said. "It's not like I'm closing my eyes. I'm reading it and I'm seeing what he's saying ... It's magical."

This ability to immerse and translate a lived or even an imagined experience into words is what is at risk of fading if we render the reins of creativity. Shortcuts may save you hours worth of brainpower, but it can hollow out the thing humans look for when reading others' work: connection.

In this vast world, humans want to know that they aren't alone in their experiences, that there's someone out there who understands their "weird" because, unlike AI, humans don't necessarily fit into an algorithm.

After all, AI cannot look into its inner child for inspiration to write out the emotions that come with childhood, nor can it look into the eyes of its shadow self.

Edited by Senna James, George Headley and Ellis Preston.

Reach the reporter at mmart533@asu.edu.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on X.

MJ is a senior reporter. She previously worked as a part-time reporter for Sci-Tech.