They were dropping like flies. At a certain point, it felt like every time I opened my phone, it was someone new. Though I wasn't familiar with a lot of them, and others I never really cared for anyway, it was sort of jarring to see just how many influencers had deplorable digital footprints.

I didn't have much else to do. It was 2020. The world was shut down and these creators were my main source of entertainment. I joined in on the jokes and mass unfollowings, telling myself and anyone who would listen that this was accountability.

There were a few cases where "cancel culture" really worked, and influencers were successfully deplatformed for their problematic behaviors. But for the rest of them, there was little change. Within weeks, everything was back to normal — and no one was truly held accountable.

When this practice became obsolete, I started to question just how effective it really was. Audiences grew less concerned with redemption and became more focused on tearing down these figures completely.

When punishment became the sole priority, it became apparent to me that cancel culture was not working — but what could replace it?

#Isoverparty

The notion of canceling a public figure through a series of online call-outs can be traced back to Black Twitter in the mid-2010s, where individuals of the community would engage in discussions surrounding emerging social movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, as well as the problematic behaviors of celebrities and brands.

At this point, much of this discourse was rooted in opening up conversations about controversial figures, but it also included more light-hearted jabs between fans of different celebrities.

One prominent example of these early cancellations involved singer-songwriter Taylor Swift, reality television star Kim Kardashian and her then husband, rapper Kanye West. According to Know Your Meme, "#isoverparty" was first used by an X user in 2015, claiming Swift as its first victim. A year later, the hashtag began trending after a phone call between Swift and Kardashian surfaced, prompting fans to question Swift's authenticity.

As a new decade approached, cancel culture began to be associated with a far more aggressive identity.

On May 10, 2019, beauty YouTube influencer Tati Westbrook posted a since-deleted video titled "BYE Sister," which detailed the feud between Westbrook and fellow YouTube influencer James Charles. In the video, Westbrook discussed her feelings of betrayal after Charles partnered with a competitor to her beauty supplement brand. She then proceeded to make accusations toward Charles, alleging he was guilty of predatory and manipulative behavior.

The release of this video resulted in Charles losing 2.6 million subscribers over the course of three days and facing an upheaval of public backlash.

Just over a week later, Charles posted his response video titled "No More Lies," in which he apologized for his betrayal to Westbrook and denied the predatory claims. With this video, Charles began flipping the narrative, and fingers started pointing at Westbrook.

After attempting to pin blame on YouTube influencers Shane Dawson and Jeffree Starr, Westbrook fell almost completely out of public favor. Despite the feud, both influencers continue to post content; however, Westbrook's engagement has decreased significantly, while Charles' subscriber count currently stands at 24 million.

This scandal marked a turning point for how creators approached public backlash as well as how audiences chose to interact with controversies. With "BYE Sister," viewers began to play an active role in the proceedings of public drama as each new detail was uncovered.

In 2023, YouTuber Colleen Ballinger, also known as Miranda Sings, took a unique route in addressing allegations that accused her of having inappropriate relationships with underage fans.

In a 10-minute video titled "hi.," Ballinger strummed on a ukulele while singing about the "toxic gossip train," refuting the claims in her own special way. The song almost immediately became a joke across the internet, with audiences expressing collective disbelief toward Ballinger's choice of "apology."

Ballinger still has an online platform and uploads content regularly; how- ever, the fallout from this controversy irreversibly damaged her reputation. Despite this, Ballinger has yet to fully address the scope of the allegations made toward her, expressing little remorse for the alleged actions that initially got her in hot water.

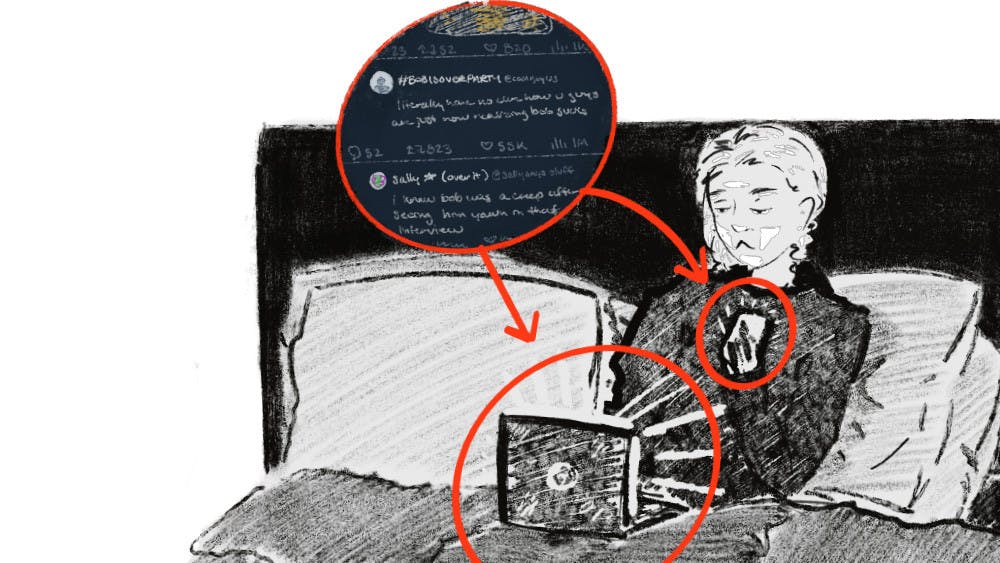

Currently, one of the most popular forms of canceling arises in resurfaced screenshots or videos from a creator’s past. In August 2024, influencer Brooke Schofield was under fire after her old tweets defending Trayvon Martin’s killer, saying slurs and admitting to racist behaviors were brought to light.

Restorative justice

In 2022, I was introduced to the idea of transformative justice. In a workshop that lasted no more than a couple of hours I was, for the first time, asked to reflect on the effectiveness of our retributive justice system.

Transformative justice, which exists under the umbrella of restorative justice, is an abolitionist framework of accountability that aims to prevent harm by addressing underlying systems that may give rise to it.

Fidelia Igwe, founder of Equitable Minds LLC, led this workshop and applied this line of thinking to scenarios often faced by students in conflict, offering tools for intervention in these situations.

A major hallmark of restorative justice is an emphasis on reconciliation through community involvement and victim-offender mediation.

Gregory Broberg, a courtesy affiliate at the School of Social Transformation, identified the two overarching pillars of restorative justice — "repairing harm and healing for victims."

In practice, a traditional restorative justice process would encompass some sort of dialogue between an offender and their victim. This could be through circle sentencing, victim panels or any meetings that give victims the opportunity to speak with the offender about the harm caused to them. They are also able to come up with a collaborative solution to repair said harm and hold the offender accountable.

"Retributive justice holds people accountable to or for something, an act, whereas restorative justice holds someone accountable to someone," Abigail Henson, an assistant professor at the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, said in reference to Danielle Sered's 2019 book "Until We Reckon."

This human-centered method of accountability offers many measurable benefits to both individuals involved and community members impacted by harm.

"For victims, it's all about restoring their voice and giving them agency in this event, whatever that event is," Broberg said. "For the offenders, it's an opportunity for them to accept accountability for the harm they did."

Restorative justice offers victims an important chance to be completely heard and have a role in how their own justice will be carried out. For offenders, restorative justice can provide a unique opportunity for growth and rehabilitation.

"The way we're going about addressing harm is not working, and therefore, there has to be another way," Henson said. "And another way that has been demonstrated with data to have high rates of satisfaction from those who have been victimized, as well as high success rates in terms of increased well-being and decreased likelihood of engaging repeatedly in harmful or illegal behavior, is restorative justice."

According to a Park University article from 2024, when applied, restorative justice models can lead to 10% to 25% decreases in recidivism rates, as well as promote victim satisfaction rates.

According to Henson, restorative justice "shifts culture by changing our perspectives of accountability" and creates an understanding of why we want to punish, why we cause harm and why violence is cyclical.

In reflecting on the effectiveness of punishment in response to harm, I've thought a lot about how cancel culture could piece into this conversation. When someone is being canceled, the ultimate goal is punishment. Through shunning, mass unfollowing, floods of negative comments and in some cases, contacting an offender's school or place of work, problematic figures are given few opportunities to redeem themselves.

When an influencer posts an apology for the harm they've caused, it's treated as a public spectacle. Will it be a Notes App apology? Are their tears even real? Why are there cuts in the video? The new standard for influencer apologies is extremely formulaic, and can make it difficult to tell which parts are out of genuine remorse or just to avoid further scrutiny.

More and more, it's hard to distinguish whether audiences truly want to see a problematic figure held accountable and grow from their actions, or if they just want the figure's head on a spike.

Seeking an alternative

When influencers like Ballinger and Charles were facing cancellation, I was admittedly aboard the toxic gossip train. I interacted with videos and comments condemning their actions, and was entertained by the mass unsubscription watch parties. However, once the conversations died down and these figures were "successfully" canceled, it didn't take long for their remaining supporters to voice their forgiveness.

In these situations, there is often conversation surrounding what communities are truly afforded the right to forgive these individuals. In Schofield's case, for example, the offensive comments she made were directly harmful toward Black, Hispanic and LGBTQIA+ communities, so it should have been these groups leading the discussion in holding her accountable. This, however, was seldom the result.

It can be extremely disheartening to see individuals who cause harm easily regain favor from those who were not affected by their actions, and who are sometimes even able to profit from being "canceled." In June 2024, TikToker Lilly Gaddis went viral after posting a video of herself cooking and casually using a racial slur, among other offensive language. Following public outrage from this video, Gaddis was terminated from her job and suspended from the app. These consequences, however, did little in pushing Gaddis to reflect on the harm she caused. In fact, she ended up doubling down on her actions and as a result, gained opportunities like being featured on podcasts and talk shows, expanding her platform even further.

Outcomes like this caused me to doubt the effectiveness of cancel culture and think about how the foundations of restorative justice could be applied as a more productive medium in ensuring problematic figures understand the harm they've caused, and are open to actively repairing it.

"People who tout themselves as abolitionists will also be calling for canceling people who have committed deep harm, but you can't be an abolitionist and be calling for the canceling of anyone," Henson said.

Within the limits of cancel culture, there is little opportunity for individuals to grow.

"You have to remember that people can grow from their past experiences, and if you allow them to grow and apologize ... [You] allow them to better themselves," Melina Becerra, a junior studying criminology and criminal justice, and forensic psychology, said.

Though the current mechanisms of cancel culture were spearheaded by Gen Z, many of its practices are no longer favored among the group.

"I feel like people are able to hide behind their screens, especially with cancel culture," Maya de La Huerta-Kainz, a junior studying community health, said. "I think it promotes a lot of cyber-bullying and it doesn't actually get any points across."

Benji Perez, a sophomore with an undefined major, said that measures of holding figures accountable could be effective "if [figures] apologize to [those] they have offended and seriously take some progressive action against what they've done."

Translating the line of thinking in restorative justice models to the processes of gaining accountability from celebrities, influencers and brands could potentially motivate reform on a larger scale.

Since younger generations will hold positions of power in the future, they are the key to making the change, according to Henson.

"So if we can shift the way they're thinking about it now, then once they get into office, they are going to be the people who are educated around these things [and] believe in the change that they're trying to pass, and will see it through," Henson said.

Restorative justice is not a perfect solution; in fact, a large critique of the system is that it allows offenders to avoid real consequences for the harm they've caused. However, restorative justice also gives offenders the opportunity to face consequences based on their victim's decision, and are required to do the work to repair this harm in a way that their victim feels would bring them justice.

"Abolition isn't about not holding accountability or creating chaos in the community, but rather understanding that nowhere in the definition of accountability is punishment," Henson said.

Edited by Leah Mesquita, Natalia Jarrett and Abigail Wilt. This story is part of The Herd Issue, which was released on November 5, 2025. See the entire publication here.

Reach the reporter at kwalls6@asu.edu and follow @KeyaneeWalls on X

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook, follow @statepressmag on X and Instagram and read our releases on Issuu.