Ben Bloomgren is tired of people trying to be politically correct about his disability.

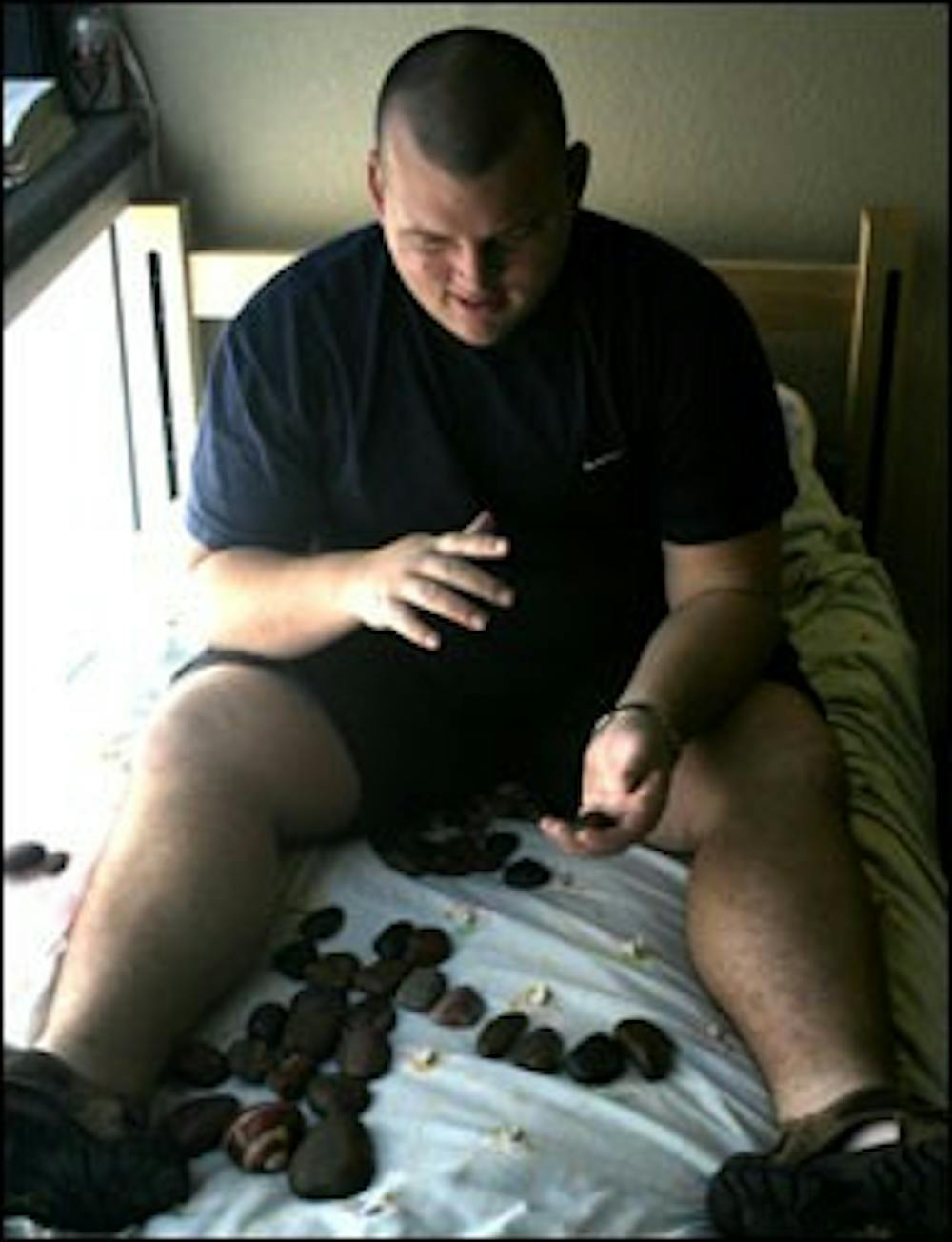

"I'm not 'visually impaired;' I'm blind," says Bloomgren while seated on his bed in his dorm room.

"Just call a spade, a spade."

Bloomgren, 22, is one of 42 students on ASU's main campus who are legally blind. Thirty-five others are visually impaired, meaning they have limited vision. Using companion dogs and walking canes, he and other students have to learn to maneuver around crowds of students, unexpected construction zones and sometimes-unhelpful pathways on a daily basis, just to get to class.

And that's just the beginning of the challenges they face.

For the first time in his life, Bloomgren is living on his own. His dorm room on the second floor in Hayden East has a bathroom, a black leather couch and shelves full of thick Braille books. A stack of audiotapes sits at the foot of his single bed, which is pushed against the back wall near the window. Braille books containing volumes of The New York Times and Rolling Stone magazine fill a box next to his desk. A deck of UNO game cards sits on top of the desk, each one stating the color and number in Braille.

He wears a gold ASU shirt; blue and yellow board shorts and Teva sandals. His head is shaved and the watch on his wrist calls out the time at the top of every hour.

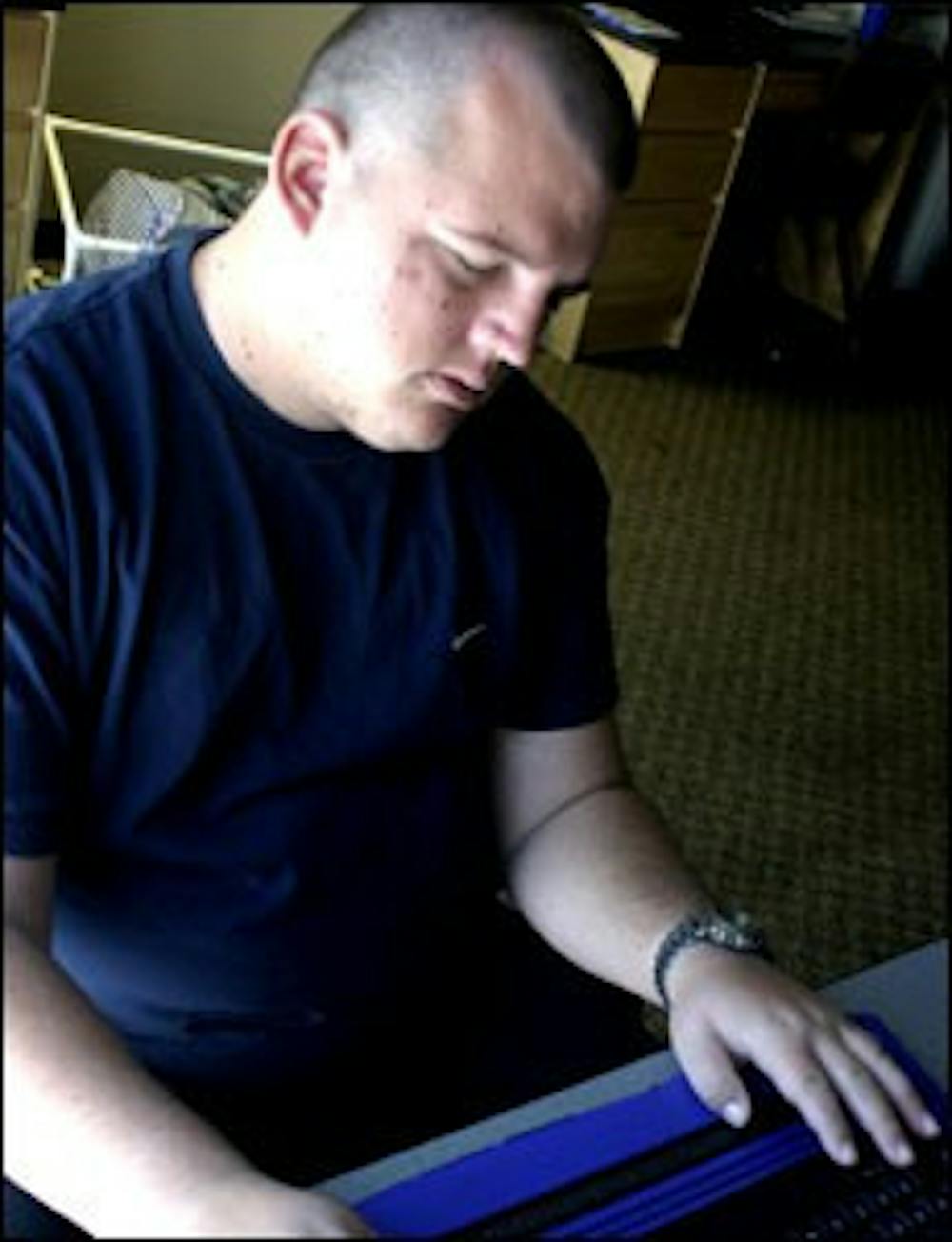

The Basha's down the street brings him his groceries -- usually Hot Pockets and microwavable burritos -- and he loves to surf the Internet in his free time using a Braille display located in front of his keyboard.

"Most people are like 'how do you work the Internet?' " he says, sliding his fingers across the raised white dots.

He punches a few keys on the keyboard and suddenly the computer begins to read pieces of text displayed on the screen out loud. He moves his fingers across the thin row of Braille from the left to the right and then as his fingers reach the end, the dots change as he continues onto the next line.

"My Internet favorites are a parent's dream. [They're] info-type sites on countries, languages and cultures," Bloomgren says with a laugh.

While he does use Braille to read much of the time, Bloomgren is quick to assert that Braille is not the only way he and other students learn.

"People think 'blind equals Braille,' but it's not the only option," says Bloomgren.

E-text is Bloomgren's favorite.

The computer program uses a Microsoft Word-like document and displays whatever chapter Bloomgren has to read, on the computer, an option many blind students prefer, according to Bloomgren.

He says he's looking forward to a new gadget that will soon be available called the iCare, because he'll be able to just scan class handouts through the machine to read them.

According to Adele Darr, disability specialist at ASU's Disability Resource Center, the computer science and engineering department has been working on the iCare reader for a year and a half and the device will help students read materials much easier.

With iCare, "the student puts the paper under the reader and [iCare] will keep reading it [out loud] to them," says Darr.

"We convert books, handouts, tests and evaluations into Braille because they can't access print," says Darr.

Students could begin using iCare as soon as late November and it's the first program of its kind in the nation, says Darr.

Darr works with blind and visually impaired students on campus to get their materials translated from regular text to Braille books as well as a host of other duties.

"They should be able to access the information because there's nothing wrong between their ears; it's in their eyes."

Darr says she's been told that ASU has one of the largest Braille labs in the country, if not the largest.

It takes four pages of Braille for every one page of print, making the books the students use very thick.

Bloomgren knows this all too well.

The King James Bible next to his bed is about 3 inches thick.

And that's only two of the 66 books of the Bible.

However, Bloomgren says many students are using the audiotapes more than Braille.

"In a college setting, books go out of date and some Braille books take $10,000 to make," says Bloomgren.

"If a professor changes the edition, there goes that money."

He admits he would rather listen to information to learn it rather than using the tips of his fingers anyway.

"Blind people have a stereotype of being tactile. I have friends that would come to someone else's house and..." Bloomgren trails off, illustrating a person learning his environment by feeling around on the table next to him.

"...Just looking. And I'd come into someone's house and just [sit]."

He identifies many of his friends by certain intricacies in their voices.

He used to be able to distinguish one friend from another because of an Indian accent, but now he says he has too many friends with Indian accents.

He listens to the chirping of the birds on campus and identifies them. A Gila woodpecker. A grackle bird.

Bloomgren, a Spanish major, managed to learn several other languages including Portuguese and French just by listening to the words and reviewing sentence structures repeatedly.

"God has given me the gift for languages," Bloomgren says.

Bloomgren says he hopes to become a Spanish translator someday.

GETTING AROUND

Unpredictability and change are the two things that turn Bloomgren's world upside down.

"I don't do change well. When we moved when I was 16, we moved a mile north," says Bloomgren.

"But it might as well have been 10,000 miles across the globe because everything I knew was in the first house."

Bloomgren says adjusting to life at ASU hasn't been as difficult as he thought it would be, but it can be frustrating at times.

"When I ask for help, [students] don't know the names of malls or streets and even building sometimes," says Bloomgren.

Getting around campus also means having to swipe his walking cane back and forth as he walks. The textured areas on each side of the sidewalk might look decorative, but in reality, it's so he knows where the edge of the sidewalk is so he doesn't walk off the path. Bloomgren orients himself with where he is based on the names of places.

One of his cues is the fountain located on Cady Mall near the Memorial Union. Bloomgren and other blind or visually impaired students use it to determine what direction they need to go to get to their dorm or another building.

Just before the beginning of every semester, the blind or visually impaired students are taught how to get around campus by orientation and mobility specialists provided by the Rehabilitation Instruction Services in the Arizona Department of Economic Security. The specialists will help them become familiar with the campus until their help is no longer necessary.

Pat Wilmot, a certified orientation and mobility specialist, helps students get settled on campus. He usually takes the students around campus the week before classes start.

"There's a tremendous amount of buildings and classrooms," says Wilmot over the phone with a laugh.

Students are usually overwhelmed with the size of the campus, he added.

"The other thing you'll see, is they write down routes and landmarks and memorize them," says Wilmot. "The minute they forget something, they could get lost. They have to be very astute."

Pedestrian traffic, trucks, bicycles and skateboards can also throw them off, while construction sites can be downright confusing, says Wilmot.

"Some people find the barriers and ask questions to get around easier," says Wilmot. "It's trial and error."

For Bloomgren, it's always trial and error just a few feet from the entrance to his dorm.

On a recent day, as he walked to his dorm, three vehicles sat illegally parked near the entrance to the gate at College Avenue and Lemon Street. He nearly walked into the first SUV parked nearby, then steered to his right to try and edge his way between the bumper and the wall, sliding his walking cane back and forth to detect open areas.

Bloomgren says he's often frustrated with the area because cars are always parked there, blocking the sidewalk.

"Cars are not supposed to park where we come in that gate," says Bloomgren with a frown.

"I wish campus police would go ticket them."

WHAT'S IT LIKE?

Bloomgren loves the people he's met at ASU, but he also often battles misconceptions; the biggest one being that blind people are incapable.

"The cardinal sin, especially, is in street crossing," he says, leaning back against the wall near his bed.

Bloomgren says people will try to help him across the street as if he's helpless. He understands they have good intentions, but most of the time it just disturbs his concentration at a somewhat stressful time.

"We're running on adrenaline and we don't know if the person on their cell phone is going to notice us -- we're hauling butt for the other side," says Bloomgren.

He knows they just don't understand and are curious.

He's reminded of that when students ask him questions like "how do you go to the bathroom?" or "how do you shower?"

It reminds him of when he was young; children would put their hands in front of his face and ask, "How many fingers am I holding up?"

"I know what they're trying to do. They want to see what I really can see," says Bloomgren.

But he does gently remind people that he isn't broken.

"Just because our eyes don't work doesn't mean everything else doesn't work," says Bloomgren.

His blue-green eyes can distinguish the difference between the light of the sun and artificial light. He can tell when it's nighttime.

He sometimes wishes he could see some things, like his parents and his brother, a sunset, animals and plants, but is glad he isn't exposed to others like pornography or the horrors of violence, racism and sexism.

Recently he toured the Tunnel of Oppression in the MU and says at the end there was a display of pictures that covered the aforementioned topics. After listening to other students' audible responses, he says he's glad he couldn't see them.

"I was born blind by the grace of God," says Bloomgren.

"When he created me, he simply left sight out of the blueprint."

He's glad he was born blind rather than having his sight and then losing it later.

"People look at it and say 'how do you live without seeing?' " says Bloomgren.

"But I've never known what it's like."

Reach the reporter at jgirard@imap2.asu.edu.