Resident assistants at ASU began leaving their positions at an alarming rate last year, and former RAs say it's because ASU Residential Life is a department dominated by fear, bullying and politics.

But in the past two semesters, many RAs have been fired or resigned. In fact, more than one in four either quit or were fired between July and February. Residential Life exhausted its applicant pool and began an emergency hiring process to fill several vacant positions, some of which remained vacant until well into the spring semester.

Residential Life officials say this is due to high expectations, a high student-to-RA ratio and students deciding the job wasn't right for them.

Former RAs tell different stories.

"Being an RA used to be an opportunity to use your social skills and creativity to get students involved," said a former RA who spoke on the condition of anonymity. "But it has become a system of following orders and having your position quantified."

His account, and those of several other former RAs' on their experiences with Residential Life, paint a vivid picture of the organization.

Becoming an RA

An RA's responsibility includes the roles of community leader, educator, administrator and role model, among other roles, according to an RA application packet.

RAs also are responsible for confronting "crisis or conflict situations," which includes enforcing University policies.

Becoming an RA is a lengthy process. Potential applicants usually start by attending Residential Life information sessions in the semester before the one for which they are applying.

There, they receive an application packet, and the real process begins.

The packet, obtained through a public records request to Residential Life, includes a short application, instructions for three one-page essays and two recommendation forms. One of the recommendation forms must be completed by an ASU faculty member.

If a prospective RA's application meets certain criteria, he or she survives the first round of cuts and is invited to "Group Process," a weekend session in which groups of applicants perform various tasks together -- all under the watchful eye of Residential Life hall directors, hall coordinators and administrators.

After Group Process and another round of cuts, the remaining applicants attend individual interviews, usually with a three-person panel of Residential Life employees -- hall directors, hall coordinators and current RAs.

Residential Life Associate Director Mistalene Calleroz said the extensive hiring process is intentional, adding that six other Pac-10 schools employ the same process.

"These are students who are living with other students," she said. "It's a high level of responsibility."

Asked to leave

Eric Wilson said he devoted three semesters of his ASU career to Residential Life. Then, one day this past February, it was over.

Wilson, a supply-chain management and computer information systems junior, was an RA in Manzanita Hall, the largest residence hall and tallest building on the ASU campus. Its 15 floors can house about 800 freshman residents. There are two RAs per floor.

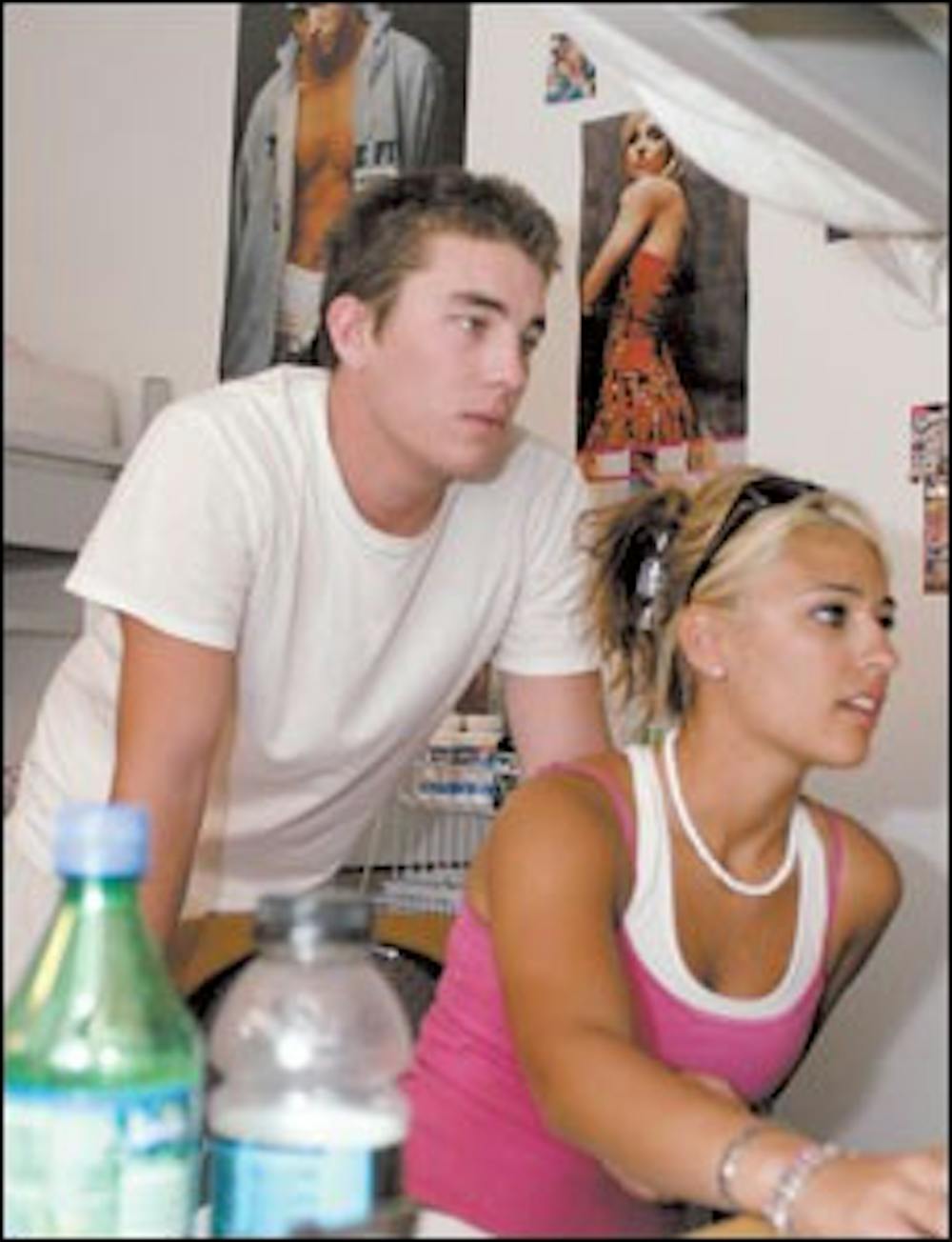

Wilson spent three semesters, plus about a month, at Manzanita. His fellow RA, biology sophomore Amanda Vitt, started at Manzanita in August.

In early February, Wilson said, "we violated a policy in our contract. We made a mistake."

He declined to give specifics, but he said when RAs had committed similar violations in the past, they were given a warning or put on probation. That didn't happen with Wilson, Vitt and two other Manzanita RAs.

"They just said, 'We're going to ask you to leave,' " he said. "There was no warning, no probation, nothing like that."

The four RAs learned of Residential Life's decision one Friday; one of them, Wilson said, didn't find out until 4:30 p.m. Residential Life's offices close at 5 p.m. and remain closed Saturday and Sunday, short-circuiting the department's internal appeals process.

"And they told us, 'You need to have your stuff packed and be moved out by 5 p.m. on Monday,' " Wilson said.

Vitt said the timing of the decision created serious problems for the four RAs, especially for the two who were from other states and had nowhere to go.

"Illinois is not that close," she said. "New Mexico, even though it's the next state over, is not that close. So for them, it was either live on the corner, or get an extension from Residential Life."

The department did allow the RAs to stay in Manzanita for a few more days, but as residents, not RAs.

It was the first policy violation for both Wilson and Vitt. Wilson described his record as an RA as "impeccable" and mentioned his membership in the National Residence Hall Honorary, an organization recognizing outstanding leadership and commitment in the residence halls.

Both said they were completely forthcoming about the situation, and both said that was probably why they lost their jobs.

"The really sad thing is that if we had lied, we'd still be working at Manzanita Hall," Wilson said. "But we decided to be honest."

Vitt said the ordeal showed her something about Residential Life. "Obviously, being honest can get you fired, so it's sort of encouraging dishonesty," she said. "It's unfortunate, but it's true."

Wilson said although he knows he has helped people as an RA, the incident devalued the time he spent in the position.

"Residential Life has made me feel like the work I did for the past year and a half wasn't worth anything," he said. "That it didn't count for anything at all."

High turnover

There are 137 RA positions on the ASU Main campus. Between July 2003 and this past February, at least 35 RAs -- 26 percent of the staff -- left their positions, either voluntarily or due to termination.

At UA, the number of RAs who left between July and the present was "less than 7 percent," according to Pam Obando, associate director of marketing services for UA Residence Life.

Calleroz said the number of RAs leaving could be attributed to "various reasons."

"Being an RA is a lifestyle," she said. "For different reasons, sometimes it's not a good fit ... Like any job, if it's not a good fit, you want to move on to something that fits better."

She said the fact that the position was one of leadership often contributes to turnover.

"The level of expectation is high for an RA," she said. "They are role models."

Vitt, though, blamed the turnover rate on "the disregard the department has for its RAs." She said after Residential Life asked her to resign, one of her residents who had applied to be an RA next fall received her invitation to Group Process.

She tore it up, Vitt said.

"She did not want to be a part of a department that treats its employees the way we were treated," Vitt said.

Wilson said his residents' reactions to the incident were disheartening.

"They were completely shocked," he said. "It's really sad to see people who wanted to be RAs see this happen, and now they don't want to anymore."

Both Wilson and Vitt said their co-workers had similar reactions, but had little choice but to remain at Manzanita.

"They're stuck; what can they do?" Wilson asked. "And they care about their residents that much."

Vitt also said the process for RAs moving to different complexes has changed, making such a move much more difficult.

"I've heard that if the people in (the Residential Life office) had their way, we wouldn't be able to change at all," she said.

Calleroz said the addition of "more and more students every year" has forced Residential Life to be less flexible.

"As we build more [residence halls], there will be more opportunities to shift," she added.

'Indentured servitude'

"It was probably one of the worst experiences of my life," said Elizabeth Apodaca, who was an RA during her last year at ASU, starting in August 2002. She graduated this past May with a degree in communication, and now works in that capacity for the Phoenix Coyotes hockey team.

Would she have been an RA another year if she hadn't been graduating?

"Not a chance."

"There were very few redeeming qualities about it," said Apodaca, who was an RA in Mariposa Hall, a smaller hall on the south side of the ASU campus. "I now know what the meaning of 'indentured servitude' is."

Apodaca said she thought many of the reasons she was hired were the same reasons she hated the job.

"The reasons I was chosen -- for being independent, and for having my own direction -- I got in trouble for a lot," she said. "At every other turn, I was in trouble for something. But those things were known about me before I was hired."

Apodaca also said several RAs on her staff left during the year and were replaced by new RAs, making it difficult to form a cohesive group.

"It's hard to match people up when you have them changing all the time," she said.

Low pay

The 2003-04 Residential Life Appointment Agreement clearly defines the compensation received by an RA: a single room in a residence hall and a $250 stipend each semester.

RAs also receive a partial meal plan for use at various dining locations on campus, "with the expectation they will eat the majority of their meals in the dining facilities." All told, the financial reward for being an RA is between $4,600 and $6,200 per academic year, according to an official Residential Life RA selection letter.

The variation occurs because of the variation in room cost between residence halls.

The compensation is similar to that at UA, according to Obando. However, she said, UA employs 217 RAs and houses 5,803 students, a ratio of about 27 residents per RA. ASU has 137 RA positions and space for about 5,500 residents, a ratio closer to 40 residents per RA.

Several of the former RAs interviewed said the compensation they received was inadequate. Vitt and Wilson noted that RAs are allowed to work only 10 hours per week at an outside job.

"I have friends who are from out of state, and they need to be able to work somewhere else," Wilson said. "At a lot of part-time jobs, you have to work at least 15 hours a week. They won't let you work 10."

Vitt said the compensation package also could affect financial aid awards, making RAs less likely to qualify for loans and scholarships.

"It does take a large financial burden off," she said, but "what we receive is nothing compared to what we could have received at an outside job."

Apodaca had a similar opinion.

"I think it's a joke what they pay you," she said. "I probably ran up $2,000 in credit card debt because I couldn't work another job. It put me in debt."

Matt Brown, a photography senior who was an RA in Mariposa at the same time as Apodaca, recalled a former Residential Life administrator saying she thought RAs were "the most important people on campus."

"But when you do the math," he said, "it's like $2 per hour what we get paid."

Calleroz said the department would be altering pay scales to reward RAs based on seniority, starting in the fall semester.

"It's important to compensate RAs according to their levels of experience," she said.

Not fun anymore

In recent months, conditions for RAs have gotten worse, according to an RA from the south side of campus who recently resigned.

"When asked what conflict I was having with the job, I said that I wasn't happy," he said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. "The response I got was that my job was to make it look fun, not to actually have fun."

According to him, Residential Life places too much emphasis on the few things RAs do wrong, not on the numerous things they do right.

"When a resident wakes you up at 3 a.m. crying, or just hangs out to 'shoot the shit' at any given time, RAs aren't given 'extra points' on their scores as RAs, but when you don't put on pointless programs, you get reprimanded," he said.

The RA said he and his fellow staff members took tests to determine how well they knew their residents and were threatened with punishment if they didn't do well. But, he said, that was just the start of what he called the "quantifying" of the RA position.

"They also count how many of our residents go to programs, and track our programming success by attendance percentages," he said. "RAs should be given -- and we used to have -- more freedom to use whatever methods they want to get a student involved, not just programming."

Resident assistants plan social, informational and community service events for residents as part of their position.

When he approached his hall director about his concerns, he said she was unreceptive. "She said, 'Your job is to make it look manageable, not to enjoy it,'" he said.

He said life as an RA wasn't always miserable for him, and that his first year in the position was extremely enjoyable.

"I spent almost every weekend talking about nothing to all the drunken residents coming back from parties," he said. "But they respected me, and we had an amazing community. This past year, there has been a push to use formal programming as the sole method and indicator to determine an RA's success.

"It just wasn't fun any more."

Hostile history

According to an independent consultant who worked with Residential Life six years ago, the organization has a history of friction with its employees.

"It's an institution that doesn't care about denigrating workers," said Gary Namie, who at the time was the co-owner of The Work Doctor, an organization that specializes in so-called "dysfunctional workplaces" to determine if supervisors bullied their employees.

Residential Life contracted Namie in March 1998 to investigate a "hostile workplace" complaint by workers at the department's Facilities and Services division, now called Facilities Management. He said what he found there was "a total, total waste."

"Our institutions are supposed to be where (students) see working models of real-world institutions," he said. "In reality, they're down-in-the-gutter institutions that are notorious for being cruel to their own labor."

Namie submitted a report to the University on April 30, 1998. In it, he detailed his discussions with groups of F&S employees -- custodians, locksmiths and other maintenance staff who make the residence halls livable before and during the school year.

He called the F&S workers' jobs a "living hell" in "a fear-driven workplace," characterized by cronyism, lack of confidentiality and disrespect for employees. That atmosphere, he said, could lead to violent retribution from abused workers.

"The most serious problem that we believe warrants a warning to all F&S, Residential Life and Student Affairs managers and employees is the threat of violence," the report says in boldfaced type. "It poses a grave danger to affected individuals."

On May 1, 1998 -- the day after Namie submitted his report -- Jody Schmit, the Residential Life employee who commissioned the study, was terminated without cause by Residential Life Director Kevin Cook, Namie said.

Calleroz would not comment on Schmit's dismissal or how Residential Life responded to the report.

Namie now works in Washington state, where he founded the Bullying Institute with his wife Ruth to combat workplace bullying.

"That treatment can only be executed when there's no accountability" among the administration, he said, adding, "If anything, the report is understated."

Namie said RAs might have it even worse than salaried employees.

"You're in a lot of trouble when you're a student worker, just because you're lower in the pecking order," he said. "They're technically employees, but ... I'm sure they have no trouble being perceived as second- or third-class citizens by the administration."

Namie said he doubted the atmosphere at Residential Life has changed since his study, mainly because Cook is still in control.

"He was too 'busy' to even come to a meeting (about the study)," Namie said. "I pity the Resident Assistants ... I can't even imagine what they're going through."

No voice

No current RAs would agree to speak with The State Press for this report. The former RAs all agreed that while they were with Residential Life, they would not have spoken to the media out of fear of losing their jobs.

"Like any business, they don't want to be reflected poorly," Wilson said. "And they don't want people who have grievances to say anything about it."

This past semester, an RA in the Honors College residence halls, Lindsey Grossman, spoke to The State Press about the Residential Life's recent revision of the "quiet hours" policy, a revision that moved the restriction up one hour and angered RAs and residents.

Vitt said when she saw the story in the paper, her immediate thought was that "that RA was going to get in trouble."

Grossman left her position at the end of the fall semester, a few weeks after the story ran, to study abroad. Reached for comment in Spain, she said she probably wouldn't have made the comment if she hadn't been leaving Residential Life anyway.

"There is that incessant threat over the heads of RAs that you could lose your job over doing something like that," Grossman said. "And of course, any job that provides housing and food is terribly inconvenient to lose in mid-semester."

She said she understood why Residential Life wouldn't want under-informed employees speaking for the department, but that "it makes RAs feel like they don't have a voice."

Calleroz said she didn't know whether RAs were told not to speak to the media, but said the department has had trouble with "misrepresentation" in the past.

"It's important to get different perspectives," she said, adding that "we also want to be sure [reporters] get accurate facts."

Not being allowed to speak with members of the media was "an unspoken understanding" among RAs, Vitt said.

"A lot of things are unspoken," Wilson said. "And a lot of politics go on." He did not elaborate.

Apodaca said many businesses, including her current employer, have similar policies.

"I understand why they do it," she said. "They want one voice coming out, and they don't want a whole bunch of different opinions getting out there.

"If you're an RA, you're representing Residential Life, no matter what anyone wants to argue about it."

Communication needed

Most of the former RAs interviewed said communication between the Residential Life office and RAs needs to improve.

"As far as I know, there has been one RA forum this year," Grossman said. "And none of the RAs' comments were written down, and ultimately, nothing budged. That sent a terrible message to us."

Wilson agreed. "The ideas that come from us are much better than the ones that come from the top down," he said. "[Upper-level officials] don't interact with the students on a daily basis, so how can they say what's best for them?"

In a large organization like Residential Life, Calleroz said, "I understand where they're coming from."

"Any time you have a central office," she said, "it makes it a challenge for communication."

She said, though, that the department recently had four information sessions about new living spaces on campus, and a total of 12 students attended. "So it goes both ways," she said.

The former RAs who spoke with The State Press had mixed feelings on whether, in retrospect, being an RA was a good experience.

"It feels like I wasted a year for nothing," Apodaca said. "I wish my experience would have been different. I know a lot of people do have great experiences ... but it really didn't happen to me."

Brown said one year of being an RA was "all I could stand."

Vitt and Wilson, though, said their time as RAs was well-spent.

"It's a wonderful experience," Wilson said, adding that his residents from the past year-and-a-half often approach and thank him.

"I had one resident come up to me and say, 'If you hadn't come and talked to me all those times in the middle of the night, I wouldn't be at school today,'" he said.

Vitt expressed similar sentiments. "People can be complete introverts, become RAs and completely turn around," she said. "It's a change for the better, for the majority of people."

Both said they had made "great friends" working as RAs.

"Being an RA is a great experience," Wilson said. "Working for ASU Residential Life is not."

Reach the reporter at noah.austin@asu.edu.