Luis Hammer was in the middle of an exam for one of his online classes when his computer screen froze.

“Take off your Apple Watch,” read a pop-up from one of the remote proctors monitoring his test.

Hammer scrambled to remove the watch. Then he showed his bare wrist to the screen, and his exam resumed.

He was using Honorlock, a remote proctoring program that uses a combination of artificial intelligence monitoring and live proctors to ensure the integrity of remote exams. Honorlock is a Google Chrome extension that enables students to take proctored exams through Canvas without going through a separate app.

“I was really surprised because I didn't know that there were people actually watching me and proctoring me while I was taking the test,” said Hammer, a sophomore studying business data analytics. “I assumed it was a computer that was doing so.”

ASU added Honorlock in May 2021 as one of three options for remote exam proctoring, a statement provided by a University spokesperson said. ASU also uses Respondus LockDown Browser and Respondus Monitor for in-person classes, according to a University document.

Respondus LockDown Browser prevents students from opening other browsers, printing, copying and pasting, and searching on the internet. Respondus Monitor builds upon the browser by having students record themselves using a webcam. The recordings are flagged for suspicious events, and professors can view the recordings after the exam, according to a Respondus webpage.

Honorlock monitors tests live using AI to alert human proctors, who pop into students’ exams via live chat to see if they are violating academic integrity policies.

Honorlock offers multiple features to prevent cheating, primarily its patented “multi-device detection” to catch students accessing exam-related content on separate devices. It also offers a feature it calls "Search and Destroy," which removes leaked questions from the web, and voice detection to ensure students aren’t collaborating with others during a test.

Students have voiced concerns about Honorlock — particularly the pop-ins and the multi-device detection feature — online since the University announced its adoption in Summer 2021, including on numerous Reddit threads.

On Google reviews, Honorlock's Google Chrome extension has a one-star rating averaged across 2,000 reviews. Complaints include fears over data, privacy and overall functionality.

In an email to faculty in May, the University announced Honorlock would be used for iCourses, ASU online classes and “high stakes exams" and replace RPNow, a proctoring service ASU previously used.

RPNow had students take a proctored exam. A proctor would review the recordings and would deliver a report to ASU, according to a page on the RPNow website dedicated to ASU.

“Each (proctoring solution) was selected in a rigorous process involving a committee of university faculty and staff and an extensive review of product functionality, user support, and security,” said the University spokesperson.

According to ASU’s contract with Honorlock, the University paid a total of $85,000 to soft launch the program over this past summer. ASU will pay $880,000 every year for three years with an option to continue through a fourth and fifth year for the same price. The total cost for five years of use is just under $4.5 million.

Behind the lock

Professors can choose which of Honorlock's features they want to enable for exams, so a student’s experience with Honorlock could vary from class to class based on their professor’s preference.

Nikolai Russell-Prusakowski, a student who started a petition against ASU using Honorlock and has used it for a class, said he is most worried about the multi-device detection feature because Honorlock’s own site seems to contradict ASU’s wording on how it works.

To use multi-device detection, Honorlock’s privacy statement says it “does not scan other computers on your network or your phone or tablet.” However, the Chrome extension does have “the ability to detect alternate computer/mobile devices that are being used to search for answers,” according to a University page explaining Honorlock for faculty.

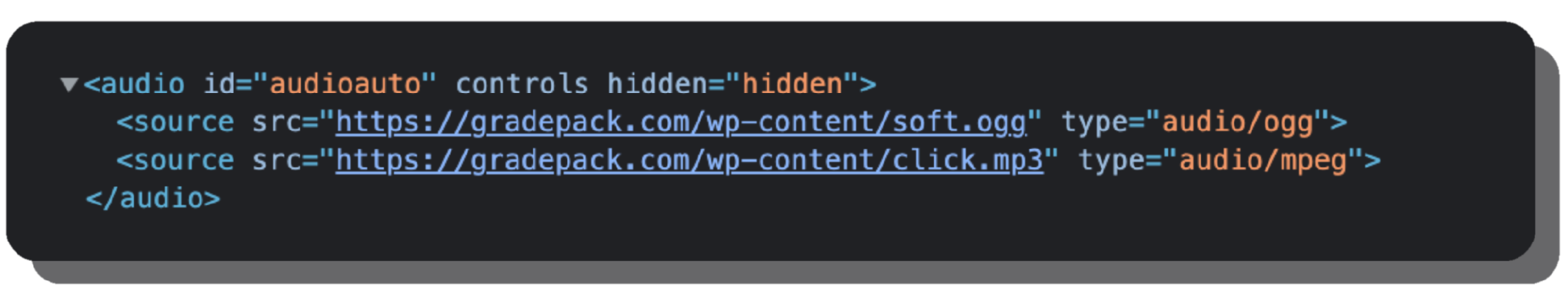

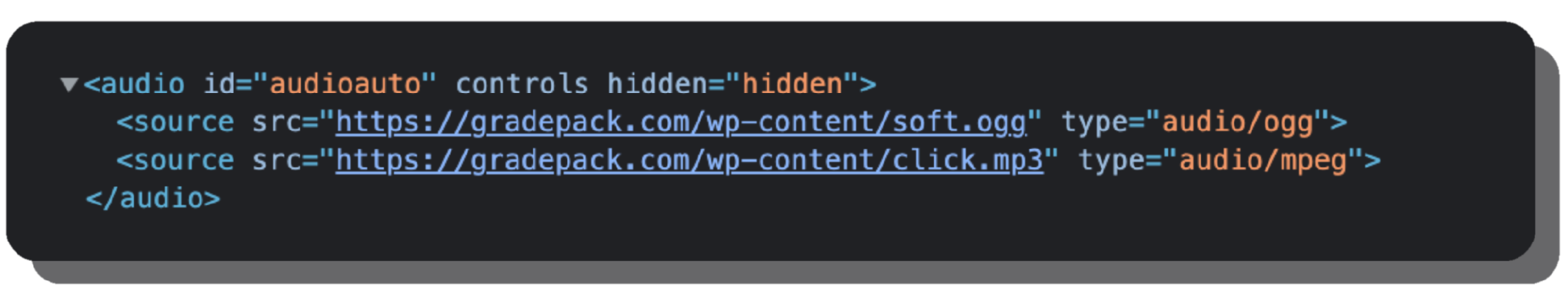

According to Honorlock's patent, its multi-device detection works as follows:

- A professor submits exam questions to Honorlock which then "watermarks" them by rewriting them using a combination of substitutes for normal English letters and characters.

- Individual watermarked questions are uploaded onto Honorlock's decoy websites, called "honeypots." If a user searches for a question by copying and pasting the watermarked question, the watermark causes the site to appear higher in search results.

- Honorlock also creates a web beacon for each page. When the student's browser loads the page, the server hosting the honeypot sites records a request. The request will include information such as:

- IP addresses, a sequence of numbers identifying devices or networks accessing the honeypot,

- URLs,

- The time the site was accessed and more.

- Honorlock collects similar information from the device the student uses to take the test.

- Additionally, each honeypot site has an event listener, a line of code that collects information from the user, including mouse clicks and movement and the time the user spends on the site, for Honorlock to use as evidence of cheating.

- If a student uses a secondary device while taking a test and visits a honeypot site, Honorlock will take the previously mentioned information from both the secondary device and the device using Honorlock and attempt to match them together.

- Instructors can also provide a small number of questions that are unique — ones not found on sites such as Quizlet or Course Hero — that are left without watermarks and placed on the honeypot sites.

- Having unique questions that are not on other sites with potential answers raises the likelihood that a student will click on a honeypot site and helps "ensure that at least a few questions have high (search engine optimized) positioning in the event that a test-taker simply retypes (not copies/pastes) the question into a search engine," according to the patent.

- One honeypot website, Buzz Folder, has over 26,000 pages of blog posts with common test questions. When a student clicks the "show answer" button for any question, the site plays a noise, which could also trigger Honorlock's sound detection. According to the patent, "the attempt can be identified and later presented as evidence of cheating during the examination."

The information collected by Honorlock during an exam is then compiled for the professor, who can then determine what to do if Honorlock has found a student may have cheated.

Depending on the violation, students can have their grades lowered, fail the class or be expelled from ASU.

Hammer said he hasn’t had significant issues with taking exams using Honorlock, but said the program's ability to monitor his actions in real-time “feels a little dystopian.”

But the use of anticipating people's activity through technology like web beacons is nothing new, said Katina Michael, professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence.

“Honorlock is like cashing in on what Google is already doing to us,” Michael said.

According to a document of answers to questions asked by ASU, Honorlock said one benefit of its live proctoring is that it "only affects your dishonest students, so honest students do not feel the punitive punishment of being watched live for the full duration of the exam."

Tess Mitchell, senior vice president of marketing for Honorlock, said in an email that proctors generally respond to actions the program's AI flags, like if someone enters the screen.

“Honorlock proctors can do proactive monitoring as well for any behaviors that might not necessarily be tracked/flagged by the AI, but go against the testing instructions set by the instructor,” Mitchell said in the email.

ASU provides suggested writing for professors to use in syllabi to explain Honorlock. The recommended syllabi writing mentions an "integrity algorithm" and asks students to "not attempt to search for answers, even if it's on a secondary device."

When asked about how the multi-device detection works, Mitchell, the Honorlock spokesperson, said "Providing an explanation about the process is not something we do as such information could compromise the integrity of the testing" and directed The State Press to the patent.

Professors can also enable Honorlock's Search and Destroy feature. When enabled, professors can upload exam questions to Honorlock, which then searches for the questions on other sites and requests the material to be removed by filing DMCA (Digital Millennium Copyright Act) copyright takedown notices.

The risk of an 'unmitigated disaster'

Daniel Marburger, a clinical professor in the Department of Economics, said the necessity of proctoring solutions extends beyond the ASU classroom.

“When we were first dabbling into the idea of online courses, it was employers that were saying to us, ‘It's extremely important to us that we know that these classes and exams have integrity,’” Marburger said.

Marburger, who has been using Respondus in his classes for about a year and a half, said without having anything to ensure academic integrity, remote test-taking would be “an unmitigated disaster.”

But David Boyles, an instructor in Writing Programs in the Department of English, said by using automated exam proctoring, ASU is missing out on an opportunity to practice better pedagogy.

“If your test is easily cheated by someone searching Google, you made a bad test," Boyles said. "You're doing a very surface-level assessment that requires very little of you as an instructor."

Shelby Livingston, a senior studying business, said her experience with Honorlock was smooth. In fact, she liked using it more than Respondus.

Despite the positive experience, Livingston said moving away from recall-based exams would be a more innovative solution than ones that require strict proctoring. Having the ability to apply learned knowledge in a real context that would mirror a workplace environment may be more helpful to the student.

“I think it's more important to know how to access that information, how to get correct information, rather than knowing it off the top of your head,” Livingston said.

A more productive way of assessing students’ understanding would be to create assignments impossible to plagiarize or cheat on, projects that go beyond sheer recall, Boyles said.

“If you designed better assessments, designed better tests, or even better got away from these banking model style tests that are just about recall and had project-based assessments, things that actually tested students’ higher order thinking skills, you wouldn't have these problems of having to catch cheaters and catch plagiarism,” Boyles said.

Honorlock as a deterrent

Automated attempts to catch cheaters are not necessarily the most effective, said Patrick Hays, a graduate student studying materials science and engineering.

Hays, who worked as an undergraduate teaching assistant in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering in the past, said that in his experience, students could bypass proctoring software “easily.”

Although Respondus, the proctoring program Hays worked with, flagged major violations, it also marked moments where nothing unusual was happening.

“I know that there were a couple of instances where I literally saw a person just sitting ramrod stiff looking at their computer screen, and during like a 10-second interval, Respondus said that there was another person in the frame and there was nothing; it was just that same person,” Hays said.

Similarly, Marburger said around 99% of the flagged moments were erroneous. It was the unmarked moments, and the existence of the recordings, that allowed him to notice legitimate academic integrity concerns.

Hays sees tools like Respondus and Honorlock as deterrents. Rather than sophisticated academic dishonesty programs, they are blunt force tools, he said.

“If somebody really wants, they'll get your bike," Hays said. "But if you've got a decent lock, it's going to deter a good amount of people from trying it."

So far, it just doesn’t seem like the University has made an effort to make students feel safe about Honorlock specifically, said Isabela Van Antwerp, a senior studying economics.

If the University could be more “transparent about everything in exactly making sure that any third party browser extension they use is super safe and secure,” Van Antwerp would feel more at ease during her exams.

By putting students under added pressure in addition to taking already stressful exams, professors create an adversarial relationship with their students, Boyles said.

“When you're putting all this stress on students, you're not actually assessing their abilities with the material,” Boyles said. “You're assessing their ability to deal with the stress and deal with this invasion of their privacy.”

Reach the reporter at alcamp12@asu.edu and follow @Anna_Lee_Camp on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.

Continue supporting student journalism and

donate to The State Press today.