The room is quiet and still. The lights dim, casting shadows that dance among the easels. A model steps into the center, letting his robe fall away. Dean Reynolds, a professor at the School of Art, adjusts the stage lights, bathing the model’s body in a soft glow.

The model poses completely exposed, redefining himself not just as a person without clothing but as a subject for students to capture. The light scratches of charcoal on paper fill the room as the sketching begins. The process of figure drawing is slow and painstaking.

Each line is careful and deliberate, but as the students continue to draw, the man and his form come alive on the page. This class offers solace in a world where students are bombarded with in- formation on social media and are increasingly reliant on artificial intelligence rather than their own skills and creativity. "AI can produce anything instantly, but that doesn’t make it good or real," Reynolds said.

Technology has altered the way we see and process information, and a lot of that change comes from convenience. Convenience has a cost, pulling us away from the patience and dedication that makes art pure, according to Reynolds. Figure drawing is like manual labor. You have to engage with what's in front of you patiently, and you can't swipe past it or filter it. Reynolds said it's impossible to replicate figure drawing with AI because purity is in the act — the slowness, the imperfection, the physical engagement with reality. To these students, figure drawing is more than just art; it’s an exercise in concentration the modern world often lacks.

Looking, seeing, knowing

The first known drawing of a man — The Shaft of the Dead Man — can be traced back to about 15,000 BCE to Lascaux cave in France during the last Ice Age. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that the art form truly blossomed, with Leonardo Da Vinci utilizing figure drawing to depict the universal nature of man, capturing stark and violent scenes.

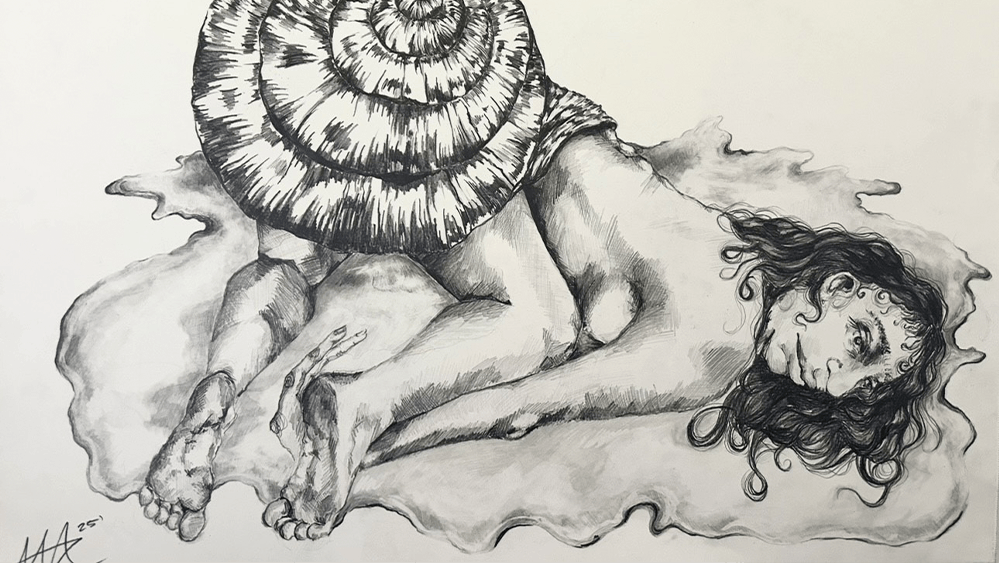

In these pieces, he sought to understand what made people tick. He used a systematic approach and strove to perfect human proportions. Because of this, other artists started to find beauty in capturing the raw human form and its symmetry. Later, the Baroque and Rococo periods moved away from the perfectionism of the Renaissance and began using figure drawing to portray intense human emotions. The nude form was utilized as a vessel, allowing artists to create expressive pieces that resonated deeply with viewers. These pieces illuminated the intensity of the human experience.

Romanticism and realism began to emerge, with pieces containing themes of passion, emotion and social commentary. Realism used nudity to convey heavier themes, featuring stark images of poverty and social injustice. Nudity allowed artists to convey difficult situations in their most authentic form, highlighting the struggles of the era. Today, figure drawing ties artists back to centuries of tradition, allowing them to explore the human body in countless ways.

"When students draw for the first time, they often just trace outlines. It's flat, stiff, wooden. But when they start to see and know — when they understand structure, volume, anatomy — their drawings come to life. It's not just about realism; it's about awareness," Reynolds said.

Reynolds encourages students to approach figure drawing like a puzzle. He describes the process as going from "looking to seeing to knowing," and explained how looking at a figure doesn't necessarily mean you have an understanding of it. To truly understand a figure, an artist must develop a relationship with the subject to notice the underlying structure and rhythm of their body.

Mariana Dean Lopez, a senior studying animation, compares this process to how she comprehends information while reading. "It's like when you're reading a paragraph and not really getting anything out of it. That’s 'looking.' 'Seeing' is when it starts to make sense. And 'knowing' is like, 'Okay, I understand the narrative now,'" she said. This awareness, Reynolds believes, is where perfection lies.

To capture a person in their most accurate form requires a high level of patience and dedication. Students scratch their charcoal on the page for the entire class, dragging lines, erasing over and over. With each stroke and careful correction, the figure gradually comes alive. Through repetition and focus, they demonstrate a level of artistic purity, marked by consistency and uninterrupted concentration.

For students, finding this focus means slowing things down. Students can use this process to build an understanding of figure drawing, improving their work day by day. Keiran Lund, a junior studying painting and drawing, has seen his work improve over time.

"You start with a surface-level understanding — just the outline — and then move toward really understanding the forms underneath, the structure and shapes that make it up. That's where 'knowing' comes in: when your practice aligns with real understanding," Lund said. He plans to apply the concepts he has learned from figure drawing to his narrative artwork in the future.

"By practicing figure studies, you learn to break down the body into simple shapes and forms," Lund said. "That helps you later when creating your own poses without needing constant photo references."

Angel Marques De Mesquita, a sophomore studying game design, finds this process meditative. "With figure drawing, I feel much more connected," Marques De Mesquita said. "There’s something about capturing emotion and anatomy that really resonates with me." She said she tends to get unmotivated easily, so this art form helps her focus on "learning muscles" — on patience and progress rather than perfection. Marques de Mesquita feels the practice of figure drawing applies "mostly to art, but I think I can apply it to other things, like starting slow, being patient and not getting frustrated too quickly."

"It's about time and effort," Reynolds said, "You can't fake it — you have to struggle, fail and try again. Purity isn't getting it right; it's the process of failing and continuing anyway. You work, you sweat, you erase and you keep going." Unlike AI, figure drawing demands intention. Each stroke is deliberate and placed on the canvas with purpose. Nothing is generated instantly or by chance and each mark is defined by observation and understanding.

This is what sets it apart. "Students begin to see how much of their lives are about distraction — about easy consumption," Reynolds said. "Here, they slow down. They start to value what’s enriching rather than what's instant. Purity becomes about depth — about eating a good meal instead of junk food." The difference between a "good meal" and "junk food" is the reward.

The refined and instant nature of AI is empty, offering little sustenance in the long run. For Marques De Mesquita, the meditative rhythm of figure drawing, from the friction of charcoal to the smudge of fingertips, feels more fulfilling. "It's rewarding when you finally get it right. You learn to enjoy the process, not just the result."

An artist's muse

Mia Aronsohn, a sophomore who models for the class, views her role very matter-of-factly. "I am just an object in the room, a statue, a muse, just like if you were to set up any other still life — apples, or whatever it is you want to draw. It's not me as myself," she said. Reynolds describes this concept as naked versus nude.

To him, naked implies power and control while nude implies equality and respect. "The model is essentially a part of the process. They pose in ways that are comfortable for them. There's a mutual understanding — an equal exchange," Reynolds said. Sitting in the classroom, this respect is clear. As soon as the model drops their robe, pencils rise and each individual's eyes trace over the model. These eyes feel different to Aronsohn.

"Oftentimes as women, you can feel eyes on you, and those eyes feel almost like darts, like they feel like they're digging in you," Aronsohn said. "But when I'm standing there, I don't feel eyes as if they're digging in me, I feel eyes as if they're passing over me and studying me, and it's almost a dance."

In the figure drawing environment, mutual respect is what makes the act safe. In the classroom, it is essential that students view the model in a professional way in order to maintain the integrity of the class. "There is a sort of agreement that you come to, that this is a professional environment. This isn't a sexual environment, this isn't a romantic environment, this is simply a job for the both of us and that's all it has to be," Aronsohn said.

Figure drawing allows for a different type of art to emerge — one that is rooted in viewing things in their original form without judgment or preconceptions. This raw simplicity is what makes figure drawing special. To Aronsohn, nudity and figure drawing are essential to our society. "Nudity has been a key aspect of art since the dawn of time. I don't think that is going to change. It would be a detriment to the world if that did change, because our bodies are the one thing that connects us all," Aronsohn said.

Edited by Leah Mesquita, Natalia Jarrett and Abigail Wilt. This story is part of The Purity Issue, which was released on December 3, 2025. See the entire publication here.

Reach the reporter at llzettle@asu.edu

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook, follow @statepressmag on X and Instagram and read our releases on Issuu.

Lucia Zettler is a part-time journalist in the magazine department. She is in her second semester at the State Press.